Post by 1dave on Mar 3, 2022 15:03:35 GMT -5

Oregon Thundereggs

www.oregongeology.org/pubs/B/B-064.pdf

(1969 - P. 214 in the PDF) - - - GEM STONES

(By R. S. Mason, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, Portland, Oreg. )

The quartz family minerals, which constitute the bulk of the semiprecious gem stones found in Oregon, very likely provide the basis for recreation for more people living in the State than any other single natural resource. Since World War II there has been a rapid growth in interest by the layman and his family in the search for, preparation of, and eventual display of the wide variety of quartz family minerals.

The "rockhounds," as they are popularly called, are attracted not only by the thrill of discovering a particularly fine specimen, but by the fact that it is a recreational pursuit which knows no season, requires no license and has no minimum or maximum qualification age for participation.

The hobby in its simplest form may entail only the collecting and tumbling or sawing of specimens. More advanced hobbyists often specialize in certain types of minerals or finished materials. The displays sponsored by the numerous "rockbound'' clubs scattered across the State reveal the wide appeal that the hobby has and the equally diverse skills and interests of its various members. Displays of jewelry are naturally one of the most popular, with collections of mineral specialties, such as zeolites and petrified wood or laboriously handcrafted objects such as flowers, butterflies, and working models of spinning wheels also finding wide attraction. There are more than 3,000 members of organized "rockbound" clubs in Oregon. The clubs have been active in recent years in standardized displays, conducting field trips, and promoting good outdoor habits. An abundance of printed material has become available on the subject of semiprecious gems,

P. 211

"rockhounding," gemmology, and related subjects. The following authors have prepared books and articles that are of interest to both the layman and professional interested in semiprecious gems : Fritzen ( 1959 ) , Frondel ( 1962) , Leechman ( 1966 ) , Parsons and Soukup ( 1961 ) , Pearl ( 1964) , Quick ( 1963 ) , Sinkankas ( 1961 ) , and Webster ( 1964 ) .

Semiprecious gems are found i n many parts of Oregon. The coast has long been a favorite haunt of the vacationist intent on finding water-polished agates, jasper, and other colorful stones. Numerous stream beds in northwestern Oregon and the Willamette Valley also yield quantities of cutting and polishing material of various kinds.

East of the Cascades, collecting areas are scattered from the Columbia River south to the California and Nevada boundaries and eastward to the Idaho line. Maps showing the principal areas in the State where semiprecious gem stones are found have been published by the Oregon Agate and Mineral Society and the Travel Information Division of the Oregon State Highway Department.

One of the early publications on Oregon gem minerals, issued by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries ( Dake, 1941 ) , has been out of print for many years, but Dr. H. C. Dake subsequently authored numerous privately printed books on the subject.

Oregon ranks high among the States in the production of semiprecious gems. Exact statistics on the value and amount of material annually produced are difficult to determine, since a large proportion of the stones are collected by nonprofessionals or by part-time operators.

Although regular dealers probably handle a considerable portion of the total, many stones are bought, sold, and traded on an individual basis. The U.S. Bureau of Mines has conservatively set the annual value of semiprecious stones produced in the State at $750,000. In all probability the actual figure is many times larger. In response to a rapidly increasing demand for information on semiprecious stones and localities where they may be obtained, several communities in the central part of the State have created "rockbound" service groups.

The Prineville and Crook County Chamber of Commerce has been particularly active in this effort. Visiting "rockhounds" can obtain maps to local digging areas, together with information on Federal rules and regulations, and campsites. In the Crook County area, there are numerous localities available to the "rockbound." Some are publicly owned, others are controlled by the Chamber, and others are privately held. The privately owned areas usually charge a daily fee plus a poundage rate. The popularity of "rockhounding" is such that thousands attend the annual "Powwow" held at Prineville.

The thunder egg is the State stone for Oregon. Of all the semiprecious materials collected in the State, the thunder egg very probably ranks first in quantity collected. The "eggs" were formed in vesicles in Tertiary lava flows which were subsequently filled with silica, both coarse- and fine-crystalline. The method of formation of thunder eggs has been described by Staples ( 1965 ) . The eventual erosion and weathering away of the lava flows released the more resistant cavity fillings. In some areas the eggs lie scattered over the surface ; in others the eggs remain imprisoned in the original matrix and must be dug out. In the latter case, the flows are usually partly weathered, and excavation is somewhat simpler than mining in solid

P. 212

rock. Most of the commercially run collecting areas strip away the overburden and expose fresh faces from time to time to facilitate recovery by "rockhounds." The thunder eggs range in weight from a few ounces to over 100 pounds.

A recent study by Peck ( 1964) of the geology of the Antelope-Ashwood area of north-central Oregon includes the following description of the nodule-bearing beds at the widely known Priday Ranch locality located about 20 miles north of the town of Madras. Although thunder eggs vary widely in appearance at the numerous localities, the geologic setting and method of formation are quite similar.

The spherulites are chiefly in the lower few feet of a weakly welded rhyolitic ash flow * * * at the base of member F of the John Day Formation, but some are in pumice lapilli higher in the ash flow and in the upper few inches of the underlying stony ash-flow sheet (number E) . The weakly welded ash flow * * * , which is 10 to 20 feet thick at the deposit, is composed of black perlitic angular lapilli of collapsed pumice in a matrix of shards and ash. Locally the basal part of the ash flow is altered to clay and to less abundant opal. Chalcedony-filled spherulites are widely distributed at this horizon ; formerly they were recovered in large numbers from a locality about 1 mile northeast of the present Priday deposit.

The Priday deposit is on a low mesa supported by the resistant ash-flow sheet of member E and is surrounded by the underlying tuffs of member D * * *.

The spherulite horizon is presented in a northward trending graben in which the Priday ash flow has been downdropped about 100 feet. The fault bounding the west side of the graben is exposed about 100 feet ( in 1958) west of the pit, where it trends N. 10" E. and dips 80" E. West of this fault the Priday ash flow with its enelosed spherulites has been uplifted and eroded.

The thunder-eggs from the Priday deposits and other localities in Oregon and Idaho have been described in detail and illustrated by Dake ( 1938 ) , Ross ( 1941 ) , Renton ( 1951 ) and Brown ( 1957 ) , so that a brief description will suffice here.

A reasonable explanation of the origin of the thunder-eggs has been advanced by Ross (1941b, p. 732 ) . He concluded that spherulites formed during cooling of the ash flow and were disrupted by the pressure of volatiles exsolved from the ash ; the resultant cavities were later filled by chalcedony during alteration of the enclosing ash flow.

Names applied to the various semiprecious gems reflect a mixture of science, geography, folklore, and fanciful description. Petrographically all the quartz family stones can be divided into two main groups ; the coarse-crystalline and fine crystalline. Table 15 lists the principal gem stones found in Oregon under these two categories.

The fine-crystalline stones can be further subdivided into groups represented by chalcedony, agate, j asper, and opal . Chalcedony has a microfibrous texture, whereas agate is distinguished by concentric or planar banding. Jasper is a microgranular type that may have been formed by metamorphic processes. Opal is a sub-microcrystalline mineral characterized by variable amounts of nonessential water.

An excellent guide to the intricacies of identifying and naming the numerous varieties of the quartz family gem stones has been published by Dake, Fleener, and Wilson ( 1938 ).

Clusters and crusts of coarse crystals are usually bought and sold "as is," with perhaps a careful cleaning the only processing attempted.

The second group comprises by far the larger portion of the semiprecious

gems collected. The fine-crystalline type of silica forms the bulk of most of the "thunder eggs," and the numerous varieties of agates and chalcedony. Although lacking in visible crystal form, the fine-crystalline stones possess a wide variety of patterns and colors.

Some agates are almost perfectly water clear, whereas others are translucent with colors of every hue. Agates may be banded, speckled, flecked, infiltrated with "moss," "plumes," "iris," or other forms of mineral impurities which impart interesting and unusual patterns, or there may be cavities which given an open-work texture to sawed slabs. One of the rarer types of gem stone found in the State is filled with water. Although most "water agates" (actually chalcedony ) or enhydroses arc quite small, specimens weighing several pounds have been found. Most enhydroses are found along the Oregon beaches.

Oregon is noted for its petrified ( silicified) wood. Excellent material, ranging in size from small agatized limbs to solid logs several feet in diameter and yards long have been found in many parts of the State. Some highly prized material has been recovered from petrified stumps still rooted in the soil that has turned to stone during the millions of years since the trees were buried. The identification techniques used on petrified wood have been described by Eubanks ( 1960, 1966) . An interesting petrified material called Tempskya has been found in limited quantity in the Greenhorn district of eastern Oregon. The Tempskya was originally a fern with a curious false trunk composed of bundles of stems. The jasper like masses reveal a distinctive pattern when cut and polished. Oregon is also

P. 214

noted for agatized seeds, nuts, and fruits. The deposits in the Clarno area of Wasco and Wheeler Counties have yielded large numbers of excellent specimens. A detailed study has been made by Scott ( 1954 ) .

A few small diamonds have been found in Oregon. Their discovery in gold placer concentrates was accidental, and no concerted efforts have been made to find others. A diamond chip about the size of a small fingernail is on display in the Roebling Collection of Native Diamonds in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and bears a label stating that it was found in Curry County, Oregon. Uncut diamonds closely resemble agates, and very likely some diamonds have been mistakenly discarded during placer gold cleanups.

Geologically, the ultramafic rocks such as serpentine, dunite, and Peridotite that are found in southwestern Oregon and also in the Blue Mountains of the northeastern part of the State could be hosts for diamonds. Recovery of diamonds from stream gravels requires, in addition to regular placer mining equipment, a section of sluice box lined with grease-covered sheet metal. Diamonds possess the peculiar property of not being wet when immersed in water thus when a diamond passes over the grease-covered metal it sticks to the grease, while all other grains and pebbles roll past, protected from the grease by a film of water adhering to their surfaces.

Semiprecious gem resources in the State are probably large. Much of the easily recovered material lying on or near the surface has been found. Future "rockhounds" will continue to discover good material on the surface, but more and more will have to come from excavations of greater and greater depth. In all probability there will be continued growth in membership of "rockhound" groups, which in turn will sponsor more conducted "digs." With the exhaustion of surface deposits and the opening up of commercial digging areas, recreational "rockhounding" will change from a largely freelance activity to a more formal and regulated one. The problems of the exploitation of semiprecious gem stone deposits on public lands have been of growing concern to the "rockhound" organizations, the commercial collector, and the public agencies charged with the administration of the lands involved. In a discussion of some of the problems, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management revealed that it is currently treating recreation mining as a specific component in its multiple-use management classifications, where appropriate ( I. W. Anderson, oral communication, 1966) .

www.oregongeology.org/pubs/B/B-064.pdf

(1969 - P. 214 in the PDF) - - - GEM STONES

(By R. S. Mason, Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, Portland, Oreg. )

The quartz family minerals, which constitute the bulk of the semiprecious gem stones found in Oregon, very likely provide the basis for recreation for more people living in the State than any other single natural resource. Since World War II there has been a rapid growth in interest by the layman and his family in the search for, preparation of, and eventual display of the wide variety of quartz family minerals.

The "rockhounds," as they are popularly called, are attracted not only by the thrill of discovering a particularly fine specimen, but by the fact that it is a recreational pursuit which knows no season, requires no license and has no minimum or maximum qualification age for participation.

The hobby in its simplest form may entail only the collecting and tumbling or sawing of specimens. More advanced hobbyists often specialize in certain types of minerals or finished materials. The displays sponsored by the numerous "rockbound'' clubs scattered across the State reveal the wide appeal that the hobby has and the equally diverse skills and interests of its various members. Displays of jewelry are naturally one of the most popular, with collections of mineral specialties, such as zeolites and petrified wood or laboriously handcrafted objects such as flowers, butterflies, and working models of spinning wheels also finding wide attraction. There are more than 3,000 members of organized "rockbound" clubs in Oregon. The clubs have been active in recent years in standardized displays, conducting field trips, and promoting good outdoor habits. An abundance of printed material has become available on the subject of semiprecious gems,

P. 211

"rockhounding," gemmology, and related subjects. The following authors have prepared books and articles that are of interest to both the layman and professional interested in semiprecious gems : Fritzen ( 1959 ) , Frondel ( 1962) , Leechman ( 1966 ) , Parsons and Soukup ( 1961 ) , Pearl ( 1964) , Quick ( 1963 ) , Sinkankas ( 1961 ) , and Webster ( 1964 ) .

Semiprecious gems are found i n many parts of Oregon. The coast has long been a favorite haunt of the vacationist intent on finding water-polished agates, jasper, and other colorful stones. Numerous stream beds in northwestern Oregon and the Willamette Valley also yield quantities of cutting and polishing material of various kinds.

East of the Cascades, collecting areas are scattered from the Columbia River south to the California and Nevada boundaries and eastward to the Idaho line. Maps showing the principal areas in the State where semiprecious gem stones are found have been published by the Oregon Agate and Mineral Society and the Travel Information Division of the Oregon State Highway Department.

One of the early publications on Oregon gem minerals, issued by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries ( Dake, 1941 ) , has been out of print for many years, but Dr. H. C. Dake subsequently authored numerous privately printed books on the subject.

Oregon ranks high among the States in the production of semiprecious gems. Exact statistics on the value and amount of material annually produced are difficult to determine, since a large proportion of the stones are collected by nonprofessionals or by part-time operators.

Although regular dealers probably handle a considerable portion of the total, many stones are bought, sold, and traded on an individual basis. The U.S. Bureau of Mines has conservatively set the annual value of semiprecious stones produced in the State at $750,000. In all probability the actual figure is many times larger. In response to a rapidly increasing demand for information on semiprecious stones and localities where they may be obtained, several communities in the central part of the State have created "rockbound" service groups.

The Prineville and Crook County Chamber of Commerce has been particularly active in this effort. Visiting "rockhounds" can obtain maps to local digging areas, together with information on Federal rules and regulations, and campsites. In the Crook County area, there are numerous localities available to the "rockbound." Some are publicly owned, others are controlled by the Chamber, and others are privately held. The privately owned areas usually charge a daily fee plus a poundage rate. The popularity of "rockhounding" is such that thousands attend the annual "Powwow" held at Prineville.

The thunder egg is the State stone for Oregon. Of all the semiprecious materials collected in the State, the thunder egg very probably ranks first in quantity collected. The "eggs" were formed in vesicles in Tertiary lava flows which were subsequently filled with silica, both coarse- and fine-crystalline. The method of formation of thunder eggs has been described by Staples ( 1965 ) . The eventual erosion and weathering away of the lava flows released the more resistant cavity fillings. In some areas the eggs lie scattered over the surface ; in others the eggs remain imprisoned in the original matrix and must be dug out. In the latter case, the flows are usually partly weathered, and excavation is somewhat simpler than mining in solid

P. 212

rock. Most of the commercially run collecting areas strip away the overburden and expose fresh faces from time to time to facilitate recovery by "rockhounds." The thunder eggs range in weight from a few ounces to over 100 pounds.

A recent study by Peck ( 1964) of the geology of the Antelope-Ashwood area of north-central Oregon includes the following description of the nodule-bearing beds at the widely known Priday Ranch locality located about 20 miles north of the town of Madras. Although thunder eggs vary widely in appearance at the numerous localities, the geologic setting and method of formation are quite similar.

The spherulites are chiefly in the lower few feet of a weakly welded rhyolitic ash flow * * * at the base of member F of the John Day Formation, but some are in pumice lapilli higher in the ash flow and in the upper few inches of the underlying stony ash-flow sheet (number E) . The weakly welded ash flow * * * , which is 10 to 20 feet thick at the deposit, is composed of black perlitic angular lapilli of collapsed pumice in a matrix of shards and ash. Locally the basal part of the ash flow is altered to clay and to less abundant opal. Chalcedony-filled spherulites are widely distributed at this horizon ; formerly they were recovered in large numbers from a locality about 1 mile northeast of the present Priday deposit.

The Priday deposit is on a low mesa supported by the resistant ash-flow sheet of member E and is surrounded by the underlying tuffs of member D * * *.

The spherulite horizon is presented in a northward trending graben in which the Priday ash flow has been downdropped about 100 feet. The fault bounding the west side of the graben is exposed about 100 feet ( in 1958) west of the pit, where it trends N. 10" E. and dips 80" E. West of this fault the Priday ash flow with its enelosed spherulites has been uplifted and eroded.

The thunder-eggs from the Priday deposits and other localities in Oregon and Idaho have been described in detail and illustrated by Dake ( 1938 ) , Ross ( 1941 ) , Renton ( 1951 ) and Brown ( 1957 ) , so that a brief description will suffice here.

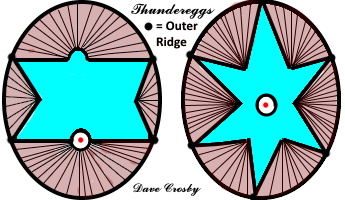

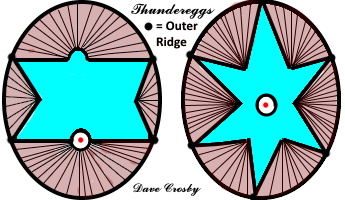

They are small spheroidal bodies, about 3 inches in average diameter, and have a cauliflower like surface crossed by low ridges. Most consist of an outer shell of pale-brown aphanitic rock and a core of white to bluish-gray chalcedony. The outer shell of each thunder-egg is composed chiefly of shards. fine ash. and collapsed pumice lapilli, all of which are altered to radially oriented sheaves of fibrous cristobalite and alkalic feldspar. The chalcedonic cores commonly contain concentric and planar bands and dendritic mineral growths and range in shape from round and highly irregular forms to geometrically regular pyritohedrons and cubes, each face of which is an inward-pointing pyramid ( Ross, 1941, pl. 2, fig. d ; Brown, 1957, pl. 3, fig. 3 ) .

These appear as squares and stars in section. - - - - -

A reasonable explanation of the origin of the thunder-eggs has been advanced by Ross (1941b, p. 732 ) . He concluded that spherulites formed during cooling of the ash flow and were disrupted by the pressure of volatiles exsolved from the ash ; the resultant cavities were later filled by chalcedony during alteration of the enclosing ash flow.

Names applied to the various semiprecious gems reflect a mixture of science, geography, folklore, and fanciful description. Petrographically all the quartz family stones can be divided into two main groups ; the coarse-crystalline and fine crystalline. Table 15 lists the principal gem stones found in Oregon under these two categories.

The fine-crystalline stones can be further subdivided into groups represented by chalcedony, agate, j asper, and opal . Chalcedony has a microfibrous texture, whereas agate is distinguished by concentric or planar banding. Jasper is a microgranular type that may have been formed by metamorphic processes. Opal is a sub-microcrystalline mineral characterized by variable amounts of nonessential water.

A detailed study of quartz and the numerous varieties of both coarse-crystalline and fine-crystalline minerals has been made by Frondel ( 1962) .

Considerable confusion exists in the terminology applied to semiprecious stones by the layman. The distinction between the various types of quartz family stones often can be resolved only by microscopic or other laboratory procedures. In all probability, there will always be some uncertainty identifying a semiprecious stone in the field, but as long as it is recognized as belonging to the quartz family rather than to some other mineral group, there is nothing really too seriously wrong.

An excellent guide to the intricacies of identifying and naming the numerous varieties of the quartz family gem stones has been published by Dake, Fleener, and Wilson ( 1938 ).

Clusters and crusts of coarse crystals are usually bought and sold "as is," with perhaps a careful cleaning the only processing attempted.

The second group comprises by far the larger portion of the semiprecious

gems collected. The fine-crystalline type of silica forms the bulk of most of the "thunder eggs," and the numerous varieties of agates and chalcedony. Although lacking in visible crystal form, the fine-crystalline stones possess a wide variety of patterns and colors.

Some agates are almost perfectly water clear, whereas others are translucent with colors of every hue. Agates may be banded, speckled, flecked, infiltrated with "moss," "plumes," "iris," or other forms of mineral impurities which impart interesting and unusual patterns, or there may be cavities which given an open-work texture to sawed slabs. One of the rarer types of gem stone found in the State is filled with water. Although most "water agates" (actually chalcedony ) or enhydroses arc quite small, specimens weighing several pounds have been found. Most enhydroses are found along the Oregon beaches.

Oregon is noted for its petrified ( silicified) wood. Excellent material, ranging in size from small agatized limbs to solid logs several feet in diameter and yards long have been found in many parts of the State. Some highly prized material has been recovered from petrified stumps still rooted in the soil that has turned to stone during the millions of years since the trees were buried. The identification techniques used on petrified wood have been described by Eubanks ( 1960, 1966) . An interesting petrified material called Tempskya has been found in limited quantity in the Greenhorn district of eastern Oregon. The Tempskya was originally a fern with a curious false trunk composed of bundles of stems. The jasper like masses reveal a distinctive pattern when cut and polished. Oregon is also

P. 214

noted for agatized seeds, nuts, and fruits. The deposits in the Clarno area of Wasco and Wheeler Counties have yielded large numbers of excellent specimens. A detailed study has been made by Scott ( 1954 ) .

A few small diamonds have been found in Oregon. Their discovery in gold placer concentrates was accidental, and no concerted efforts have been made to find others. A diamond chip about the size of a small fingernail is on display in the Roebling Collection of Native Diamonds in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and bears a label stating that it was found in Curry County, Oregon. Uncut diamonds closely resemble agates, and very likely some diamonds have been mistakenly discarded during placer gold cleanups.

Geologically, the ultramafic rocks such as serpentine, dunite, and Peridotite that are found in southwestern Oregon and also in the Blue Mountains of the northeastern part of the State could be hosts for diamonds. Recovery of diamonds from stream gravels requires, in addition to regular placer mining equipment, a section of sluice box lined with grease-covered sheet metal. Diamonds possess the peculiar property of not being wet when immersed in water thus when a diamond passes over the grease-covered metal it sticks to the grease, while all other grains and pebbles roll past, protected from the grease by a film of water adhering to their surfaces.

Semiprecious gem resources in the State are probably large. Much of the easily recovered material lying on or near the surface has been found. Future "rockhounds" will continue to discover good material on the surface, but more and more will have to come from excavations of greater and greater depth. In all probability there will be continued growth in membership of "rockhound" groups, which in turn will sponsor more conducted "digs." With the exhaustion of surface deposits and the opening up of commercial digging areas, recreational "rockhounding" will change from a largely freelance activity to a more formal and regulated one. The problems of the exploitation of semiprecious gem stone deposits on public lands have been of growing concern to the "rockhound" organizations, the commercial collector, and the public agencies charged with the administration of the lands involved. In a discussion of some of the problems, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management revealed that it is currently treating recreation mining as a specific component in its multiple-use management classifications, where appropriate ( I. W. Anderson, oral communication, 1966) .