McDermitt Nevada & Transitional Nodules

Mar 27, 2022 15:21:28 GMT -5

RWA3006, RickB, and 2 more like this

Post by 1dave on Mar 27, 2022 15:21:28 GMT -5

It was here at McDermitt Nevada that the Kid discovered “transitional nodules.” Note he did not call them “transitional thundereggs” as some seem to think.

thundereggs.jimdofree.com/north-america/usa-a-ca/california/

They are kind of like Cathedral agate from Uruguayan and Brazilian Basalt, but occasionally this happens in rhyolite.

I’ll let Paul tell the story in his own words. - - -

thundereggs.jimdofree.com/north-america/usa-a-ca/california/

They are kind of like Cathedral agate from Uruguayan and Brazilian Basalt, but occasionally this happens in rhyolite.

I’ll let Paul tell the story in his own words. - - -

Chapter Seven Transitional Nodules:

In 1973, when I discovered the very odd occurrence of amygdaloid-shaped nodules in a traditional thunderegg deposit east of McDermitt, Nevada, I thought about the strange nodules I had seen at the rock shop there.

I visited the shop after the dig, to share the experience and inquire of the odd nodules I had earlier seen in his yard. The owner was quite generous, supplying a map and trading some nodules. He said that there were never many of them to begin with, and digging, short of blasting, was impossible.

When he saw my gas-powered jackhammer and powder, he wanted to shut shop and go with me, but customers were there, and so I promised to show him the results when I was done.

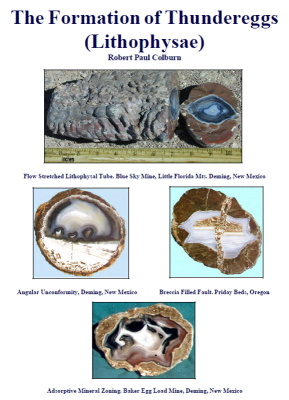

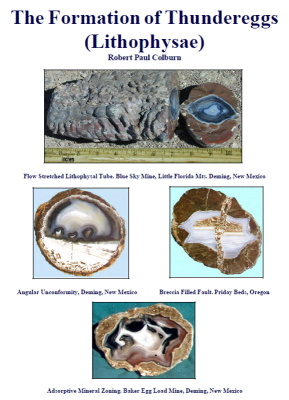

Figure 7.03

The small deposit where the nodules came from is about 16 miles west of McDermitt, on some interesting roads, but I made it without using my 4-wheel drive. About 4 ½ miles before reaching the site, there is a good place to camp and get water, called Cottonwood Creek. The deposit itself covers only about a quarter-acre, located near the southwest corner of the northwest 1/4 of section 31, T-40-S, R-41-E on the Bretz Mine 7.5 minute quadrangle.

Pieces of nodules and agate are scattered over a round, barren slope projecting east, at the end of which two small, dry washes converge. The freshly broken pieces show a matrix that is identical to the rock from which the nodules have weathered. The nodules are amygdaloidal, the weathered ones are oxidized brown on their surfaces, and look like volcanic bombs while those dug from in-situ look like the rock from which they come, somewhat like sandy cement. The matrix inside the nodules is darker, silicified, and thin, usually making up 10% or less of a cut face, which shows a solid core of red, black, and blue fortification agate. The larger specimens have white waterline agate suspensions, often with cavities at their tops lined with quartz crystals.

At the time, I did not give much attention to this deposit, because first, I thought I would never

again see another like it, and second, it was intuitively difficult at the time. But then, in the winter of

1975, I discovered a deposit of nodules almost identical in form, more than 500 miles to the south.

This deposit is located 12 miles north of Barstow, California, on the Fort Irwin Road, at a point where

a dim, 4-wheel drive track crosses a wash and heads toward a grayish saddle between two darker,

reddish-brown rocky hills, almost a mile west of the paved road. The approximate location is near the

section line in the southwest quarter, section 17, T-11-N, R-1-E. in the Trona 1/250,000 topographic

map.

It turned out to be only the first of four deposits of “flat,” transitional nodules I was to find, in the

Barstow vicinity and elsewhere.

These nodules are larger than average, and have a matrix that looks even more like concrete

than those from McDermitt. They are filled with blue fortification agate, and the larger ones are

hollow, with waterline agate and floors at the very bottom (See Figure 7.03). The material containing

Chapter Seven: Transitional Nodules - 181

The specimen in Figure 7.03 represents a transitional nodule from north of Barstow, California, cut through the narrow axis. The waterline agate and floor are at the bottom, exactly the way the nodule was found in-situ, indicating that little, if any, deformation occurred throughout its history. Therefore, its position, perpendicular to the earth, indicates that the flowage was upward when the igneous mass solidified, and that it did not form in a horizontal flow. Rather, it formed at the top of a vent or fissure, or even in a shallow part of a dike. Note the resilicification of decomposed product (lighter green at the top of the nodule) and the rare “sun bursts” of aragonite and zeolite (sagenite) composite which grew from the walls of the cavity before being filled with agate. The matrix is thick, resulting from concretionary growth, rather than existing before solidification, as it would in lithophysae. The cavity walls are ragged from the tearing of the viscous material when gas pressure forced it open. Photo by Chris Algar. Actual size, 12 inches.

the nodules is identical to the matrix of the nodule itself, with about ½ inch of decomposed product

between them, and hard enough that the scarce nodules had to be blasted out with light charges of 40%

dynamite. They were positioned in-situ with the waterline at the bottom, which indicates no

deformation of the site, at least since the waterline agate was emplaced, and judging from how the

deposit is situated, little or no deformation occurred throughout its history.

The matrix (shells) of transitional nodules and a few lithophysae belong to the “granular” category (see page 131) which texturally are unlike aphanitic or porphyritic lithophysae. Some transitional nodules are found in perlite which will be covered shortly. Star-vectoring in granular individuals found in perlite is poor to fair and random in quality, often in a single deposit, see Figures 6.03, 7.06, 7.07 and 9.08. Close inspection with a good magnifying lense reveals that spherulitic crystallization took place and a more sophisticated analysis would probably find cristobalite, albeit with a more suppressed effect in regards to star-vectoring than that which is seen in lithophysae where perthite is the dominant groundmass.

In 1973, when I discovered the very odd occurrence of amygdaloid-shaped nodules in a traditional thunderegg deposit east of McDermitt, Nevada, I thought about the strange nodules I had seen at the rock shop there.

I visited the shop after the dig, to share the experience and inquire of the odd nodules I had earlier seen in his yard. The owner was quite generous, supplying a map and trading some nodules. He said that there were never many of them to begin with, and digging, short of blasting, was impossible.

When he saw my gas-powered jackhammer and powder, he wanted to shut shop and go with me, but customers were there, and so I promised to show him the results when I was done.

Figure 7.03

The small deposit where the nodules came from is about 16 miles west of McDermitt, on some interesting roads, but I made it without using my 4-wheel drive. About 4 ½ miles before reaching the site, there is a good place to camp and get water, called Cottonwood Creek. The deposit itself covers only about a quarter-acre, located near the southwest corner of the northwest 1/4 of section 31, T-40-S, R-41-E on the Bretz Mine 7.5 minute quadrangle.

Pieces of nodules and agate are scattered over a round, barren slope projecting east, at the end of which two small, dry washes converge. The freshly broken pieces show a matrix that is identical to the rock from which the nodules have weathered. The nodules are amygdaloidal, the weathered ones are oxidized brown on their surfaces, and look like volcanic bombs while those dug from in-situ look like the rock from which they come, somewhat like sandy cement. The matrix inside the nodules is darker, silicified, and thin, usually making up 10% or less of a cut face, which shows a solid core of red, black, and blue fortification agate. The larger specimens have white waterline agate suspensions, often with cavities at their tops lined with quartz crystals.

At the time, I did not give much attention to this deposit, because first, I thought I would never

again see another like it, and second, it was intuitively difficult at the time. But then, in the winter of

1975, I discovered a deposit of nodules almost identical in form, more than 500 miles to the south.

This deposit is located 12 miles north of Barstow, California, on the Fort Irwin Road, at a point where

a dim, 4-wheel drive track crosses a wash and heads toward a grayish saddle between two darker,

reddish-brown rocky hills, almost a mile west of the paved road. The approximate location is near the

section line in the southwest quarter, section 17, T-11-N, R-1-E. in the Trona 1/250,000 topographic

map.

It turned out to be only the first of four deposits of “flat,” transitional nodules I was to find, in the

Barstow vicinity and elsewhere.

These nodules are larger than average, and have a matrix that looks even more like concrete

than those from McDermitt. They are filled with blue fortification agate, and the larger ones are

hollow, with waterline agate and floors at the very bottom (See Figure 7.03). The material containing

Chapter Seven: Transitional Nodules - 181

The specimen in Figure 7.03 represents a transitional nodule from north of Barstow, California, cut through the narrow axis. The waterline agate and floor are at the bottom, exactly the way the nodule was found in-situ, indicating that little, if any, deformation occurred throughout its history. Therefore, its position, perpendicular to the earth, indicates that the flowage was upward when the igneous mass solidified, and that it did not form in a horizontal flow. Rather, it formed at the top of a vent or fissure, or even in a shallow part of a dike. Note the resilicification of decomposed product (lighter green at the top of the nodule) and the rare “sun bursts” of aragonite and zeolite (sagenite) composite which grew from the walls of the cavity before being filled with agate. The matrix is thick, resulting from concretionary growth, rather than existing before solidification, as it would in lithophysae. The cavity walls are ragged from the tearing of the viscous material when gas pressure forced it open. Photo by Chris Algar. Actual size, 12 inches.

the nodules is identical to the matrix of the nodule itself, with about ½ inch of decomposed product

between them, and hard enough that the scarce nodules had to be blasted out with light charges of 40%

dynamite. They were positioned in-situ with the waterline at the bottom, which indicates no

deformation of the site, at least since the waterline agate was emplaced, and judging from how the

deposit is situated, little or no deformation occurred throughout its history.

The matrix (shells) of transitional nodules and a few lithophysae belong to the “granular” category (see page 131) which texturally are unlike aphanitic or porphyritic lithophysae. Some transitional nodules are found in perlite which will be covered shortly. Star-vectoring in granular individuals found in perlite is poor to fair and random in quality, often in a single deposit, see Figures 6.03, 7.06, 7.07 and 9.08. Close inspection with a good magnifying lense reveals that spherulitic crystallization took place and a more sophisticated analysis would probably find cristobalite, albeit with a more suppressed effect in regards to star-vectoring than that which is seen in lithophysae where perthite is the dominant groundmass.