Post by 1dave on Jan 1, 2024 14:39:28 GMT -5

Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle is a small comet―its nucleus measures only about 2.24 miles (3.6 kilometers) across. It takes Tempel-Tuttle 33 years to orbit the sun once. Tempel-Tuttle last reached perihelion (closest approach to the sun) in 1998 and will return again in 2031. Responsible for the Leonid meteor Showers.

Giving an insight into thoughts and feelings of witnesses at the time are the following description of the Wall family’s experience as written by Bruna McGuire and Betty Wall:

“The stars showered down so thickly and fast that it looked as though every star in the heavens was falling. When they touched the ground, they burst and drifted away. Stars were still falling when the Sun arose the next morning. Never before had there been such a sight witnessed, nor has there been since the greatest meteoric display of our age.”

Astronomer Denison Olmsted Gave a much longer explanation, gathering information from newspapers from all over North America: "LETTER XXVII. - METEORIC SHOWERS."

"Oft shalt thou see, ere brooding storms arise, Star after star glide headlong down the skies, And, where they shot, long trails of lingering light Sweep far behind, and gild the shades of night."—Virgil.

Few subjects of astronomy have excited a more general interest, for several years past, than those extraordinary exhibitions of shooting stars, which have acquired the name of meteoric showers. My reason for introducing the subject to your notice, in this place, is, that these small bodies are, as I believe, derived from nebulous or cometary bodies, which belong to the solar system, and which, therefore, ought to be considered, before we take our leave of this department of creation, and naturally come next in order to comets.

The attention of astronomers was particularly directed to this subject by the extraordinary shower of meteors which occurred on the morning of the thirteenth of November, 1833. I had the good fortune to witness these grand celestial fire-works, and felt a strong desire that a phenomenon, which, as it afterwards appeared, was confined chiefly to North America, should here command that diligent inquiry into its causes, which so sublime a spectacle might justly claim.

As I think you were not so happy as to witness this magnificent display, I will endeavor to give you some faint idea of it, as it appeared to me a little before daybreak. Imagine a constant succession of fire-balls, resembling sky-rockets, radiating in all directions from a point in the heavens a few degrees southeast of the zenith, and following the arch of the sky towards the horizon. They commenced their progress at different distances from the radiating point; but their directions were uniformly such, that the lines they described, if produced upwards, would all have met in the same part of the heavens. Around this point, or imaginary radiant, was a circular space of several degrees, within which no meteors were observed. The balls, as they traveled down the vault, usually left after them a vivid streak of light; and, just before they disappeared, exploded, or suddenly resolved themselves into smoke. No report of any kind was observed, although we listened attentively.

Beside the foregoing distinct concretions, or individual bodies, the atmosphere exhibited phosphoric lines, following in the train of minute points, that shot off in the greatest abundance in a northwesterly direction. These did not so fully copy the figure of the sky, but moved in paths more nearly rectilinear, and appeared to be much nearer the spectator than the fire-balls. The light of their trains was also of a paler hue, not unlike that produced by writing with a stick of phosphorus on the walls of a dark room. The number of these luminous trains increased and diminished alternately, now and then crossing the field of view, like snow drifted before the wind, although, in fact, their course was towards the wind.

From these two varieties, we were presented with meteors of various sizes and degrees of splendor: some were mere points, while others were larger and brighter than Jupiter or Venus; and one, seen by a credible witness, at an earlier hour, was judged to be nearly as large as the moon. The flashes of light, although less intense than lightning, were so bright, as to awaken people in their beds. One ball that shot off in the northwest direction, and exploded a little northward of[348] the star Capella, left, just behind the place of explosion, a phosphorescent train of peculiar beauty. This train was at first nearly straight, but it shortly began to contract in length, to dilate in breadth, and to assume the figure of a serpent drawing itself up, until it appeared like a small luminous cloud of vapor. This cloud was borne eastward, (by the wind, as was supposed, which was blowing gently in that direction,) opposite to the direction in which the meteor itself had moved, remaining in sight several minutes. The point from which the meteors seemed to radiate kept a fixed position among the stars, being constantly near a star in Leo, called Gamma Leonis.

Such is a brief description of this grand and beautiful display, as I saw it at New Haven. The newspapers shortly brought us intelligence of similar appearances in all parts of the United States, and many minute descriptions were published by various observers; from which it appeared, that the exhibition had been marked by very nearly the same characteristics wherever it had been seen. Probably no celestial phenomenon has ever occurred in this country, since its first settlement, which was viewed with so much admiration and delight by one class of spectators, or with so much astonishment and fear by another class. It strikingly evinced the progress of knowledge and civilization, that the latter class was comparatively so small, although it afforded some few examples of the dismay with which, in barbarous ages of the world, such spectacles as this were wont to be regarded. One or two instances were reported, of persons who died with terror; many others thought the last great day had come; and the untutored black population of the South gave expression to their fears in cries and shrieks.

After collecting and collating the accounts given in all the periodicals of the country, and also in numerous letters addressed either to my scientific friends or to myself, the following appeared to be the leading facts attending the phenomenon. The shower pervaded nearly the whole of North America, having appeared in nearly equal splendor from the British possessions on the north to the West-India Islands and Mexico on the south, and from sixty-one degrees of longitude east of the American coast, quite to the Pacific Ocean on the west. Throughout this immense region, the duration was nearly the same. The meteors began to attract attention by their unusual frequency and brilliancy, from nine to twelve o'clock in the evening; were most striking in their appearance from two to five; arrived at their maximum, in many places, about four o'clock; and continued until rendered invisible by the light of day. The meteors moved either in right lines, or in such apparent curves, as, upon optical principles, can be resolved into right lines. Their general tendency was towards the northwest, although, by the effect of perspective, they appeared to move in various directions.

Such were the leading phenomena of the great meteoric shower of November 13, 1833. For a fuller detail of the facts, as well as of the reasoning's that were built on them, I must beg leave to refer you to some papers of mine in the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth volumes of the American Journal of Science.

Soon after this wonderful occurrence, it was ascertained that a similar meteoric shower had appeared in 1799, and, what was remarkable, almost at exactly the same time of year, namely, on the morning of the twelfth of November; and we were again surprised as well as delighted, at receiving successive accounts from different parts of the world of the phenomenon, as having occurred on the morning of the same thirteenth of November, in 1830, 1831, and 1832. Hence this was evidently an event independent of the casual changes of the atmosphere; for, having a periodical return, it was undoubtedly to be referred to astronomical causes, and its recurrence, at a certain definite period of the year, plainly indicated some relation to the revolution of the earth around the sun. It remained, however, to develop the nature of this relation, by investigating, if possible, the origin of the meteors. The views to which I was led on this subject suggested the probability that the same phenomenon would recur on the corresponding seasons of the year, for at least several years afterwards; and such proved to be the fact, although the appearances, at every succeeding return, were less and less striking, until 1839, when, so far as I have heard, they ceased altogether.

Mean-while, two other distinct periods of meteoric showers have, as already intimated, been determined; namely, about the ninth of August, and seventh of December. The facts relative to the history of these periods have been collected with great industry by Mr. Edward C. Herrick; and several of the most ingenious and most useful conclusions, respecting the laws that regulate these singular exhibitions, have been deduced by Professor Twining. Several of the most distinguished astronomers of the Old World, also, have engaged in these investigations with great zeal, as Messrs. Arago and Biot, of Paris; Doctor Olbers, of Bremen; M. Wartmann, of Geneva; and M. Quetelet, of Brussels.

But you will be desirous to learn what are the conclusions which have been drawn respecting these new and extraordinary phenomena of the heavens. As the inferences to which I was led, as explained in the twenty-sixth volume of the 'American Journal of Science,' have, at least in their most important points, been sanctioned by astronomers of the highest respectability, I will venture to give you a brief abstract of them, with such modifications as the progress of investigation since that period has rendered necessary.

The principal questions involved in the inquiry were the following:—Was the origin of the meteors within the atmosphere, or beyond it? What was the height of the place above the surface of the earth? By what force were the meteors drawn or impelled towards the earth? In what directions did they move? With what velocity? What was the cause of their light and[351] heat? Of what size were the larger varieties? At what height above the earth did they disappear? What was the nature of the luminous trains which sometimes remained behind? What sort of bodies were the meteors themselves; of what kind of matter constituted; and in what manner did they exist before they fell to the earth? Finally, what relations did the source from which they emanated sustain to our earth?

In the first place, the meteors had their origin beyond the limits of our atmosphere. We know whether a given appearance in the sky is within the atmosphere or beyond it, by this circumstance: all bodies near the earth, including the atmosphere itself, have a common motion with the earth around its axis from west to east. When we see a celestial object moving regularly from west to east, at the same rate as the earth moves, leaving the stars behind, we know it is near the earth, and partakes, in common with the atmosphere, of its diurnal rotation: but when the earth leaves the object behind; or, in other words, when the object moves westward along with the stars, then we know that it is so distant as not to participate in the diurnal revolution of the earth, and of course to be beyond the atmosphere. The source from which the meteors emanated thus kept pace with the stars, and hence was beyond the atmosphere.

In the second place, the height of the place whence the meteors proceeded was very great, but it has not yet been accurately determined. Regarding the body whence the meteors emanated after the similitude of a cloud, it seemed possible to obtain its height in the same manner as we measure the height of a cloud, or indeed the height of the moon. Although we could not see the body itself, yet the part of the heavens whence the meteors came would indicate its position. This point we called the radiant; and the question was, whether the radiant was projected by distant observers on different parts of the sky; that is, whether it had any parallax. I took much pains to ascertain the truth of this matter, by corresponding with various[352] observers in different parts of the United States, who had accurately noted the position of the radiant among the fixed stars, and supposed I had obtained such materials as would enable us to determine the parallax, at least approximately; although such discordance existed in the evidence as reasonably to create some distrust of its validity. Putting together, however, the best materials I could obtain, I made the height of the radiant above the surface of the earth twenty-two hundred and thirty-eight miles. When, however, I afterwards obtained, as I supposed, some insight into the celestial origin of the meteors, I at once saw that the meteoric body must be much further off than this distance; and my present impression is, that we have not the means of determining what its height really is. We may safely place it at many thousand miles.

In the third place, with respect to the force by which the meteors were drawn or impelled towards the earth, my first impression was, that they fell merely by the force of gravity; but the velocity which, on careful investigation by Professor Twining and others, has been ascribed to them, is greater than can possibly result from gravity, since a body can never acquire, by gravity alone, a velocity greater than about seven miles per second. Some other cause, beside gravity, must therefore act, in order to give the meteors so great an apparent velocity.

In the fourth place, the meteors fell towards the earth in straight lines, and in directions which, within considerable distances, were nearly parallel with each other. The courses are inferred to have been in straight lines, because no others could have appeared to spectators in different situations to have described arcs of great circles. In order to be projected into the arc of a great circle, the line of descent must be in a plane passing through the eye of the spectator; and the intersection of such planes, passing through the eyes of different spectators, must be straight lines. The lines of direction are inferred to have been parallel, on account of their apparent radiation from one point, that[353] being the vanishing point of parallel lines. This may appear to you a little paradoxical, to infer that lines are parallel, because they diverge from one and the same point; but it is a well-known principle of perspective, that parallel lines, when continued to a great distance from the eye, appear to converge towards the remoter end. You may observe this in two long rows of trees, or of street lamps.

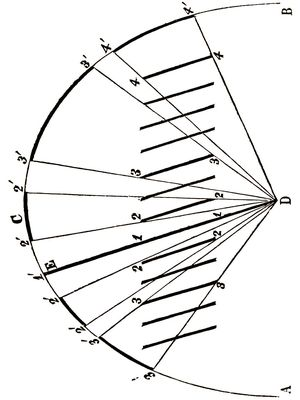

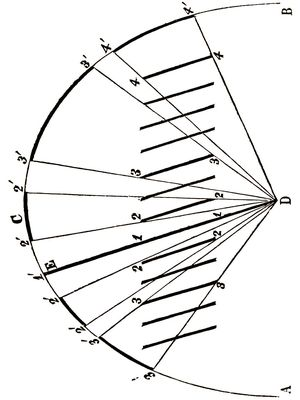

Fig. 69.

Some idea of the manner in which the meteors fell, and of the reason of their apparent radiation from a common point, may be gathered from the annexed diagram. Let A B C, Fig. 69, represent the vault of the sky, the center of which, D, being the place of the spectator. Let 1, 2, 3, &c., represent parallel lines directed towards the earth. A luminous body descending through 1´ 1, coinciding with the line D E, coincident with the axis of vision, (or the line drawn from the meteoric body to the eye,) would appear stationary all the while at 1´, because distant bodies always appear stationary when they are moving either directly towards us or directly from us. A body descending through 2 2, would seem to describe the short arc 2´ 2´, appearing to move on the concave of the sky between the lines drawn from the eye to the two extremities of its line of motion; and, for a similar reason, a body descending through 3 3, would appear to describe the larger arc 3´ 3´. Hence, those meteors which fell nearer to the axis of vision, would describe shorter arcs, and move slower, while those which were further from the axis and nearer the horizon would appear to describe longer arcs, and to move with greater velocity; the meteors would all seem to radiate from a common center, namely, the point where the axis of vision met the celestial vault; and if any meteor chanced to move directly in the line of vision, it would be seen as a luminous body, stationary, for a few seconds, at the center of radiation. To see how exactly the facts, as observed, corresponded to these inferences, derived from the supposition that the meteors moved in parallel lines, take the following description, as given immediately after the occurrence, by Professor Twining. "In the vicinity of the radiant point, a few star-like bodies were observed, possessing very little motion, and leaving very little length of trace. Further off, the motions were more rapid and the traces longer; and most rapid of all, and longest in their traces, were those which originated but a few degrees above the horizon, and descended down to it."

In the fifth place, had the meteors come from a point twenty-two hundred and thirty-eight miles from the earth, and derived their apparent velocity from gravity[355] alone, then it would be found, by a very easy calculation, that their actual velocity was about four miles per second; but, as already intimated, the velocity observed was estimated much greater than could be accounted for on these principles; not less, indeed, than fourteen miles per second, and, in some instances, much greater even than this. The motion of the earth in its orbit is about nineteen miles per second; and the most reasonable supposition we can make, at present, to account for the great velocity of the meteors, is, that they derived a relative motion from the earth's passing rapidly by them,—a supposition which is countenanced by the fact that they generally tended westward contrary to the earth's motion in its orbit.

In the sixth place, the meteors consisted of combustible matter, and took fire, and were consumed, in traversing the atmosphere. That these bodies underwent combustion, we had the direct evidence of the senses, inasmuch as we saw them burn. That they took fire in the atmosphere, was inferred from the fact that they were not luminous in their original situations in space, otherwise, we should have seen the body from which they emanated; and had they been luminous before reaching the atmosphere, we should have seen them for a much longer period than they were in sight, as they must have occupied a considerable time in descending towards the earth from so great a distance, even at the rapid rate at which they traveled. The immediate consequence of the prodigious velocity with which the meteors fell into the atmosphere must be a powerful condensation of the air before them, retarding their progress, and producing, by a sudden compression of the air, a great evolution of heat. There is a little instrument called the air-match, consisting of a piston and cylinder, like a syringe, in which we strike a light by suddenly forcing down the piston upon the air below. As the air cannot escape, it is suddenly compressed, and gives a spark sufficient to light a piece of tinder at the bottom of the cylinder. Indeed, it is a well[356]-known fact, that, whenever air is suddenly and forcibly compressed, heat is elicited; and, if by such a compression as may be given by the hand in the air-match, heat is evolved sufficient to fire tinder, what must be the heat evolved by the motion of a large body in the atmosphere, with a velocity so immense. It is common to resort to electricity as the agent which produces the heat and light of shooting stars; but even were electricity competent to produce this effect, its presence, in the case before us, is not proved; and its agency is unnecessary, since so swift a motion of the meteors themselves, suddenly condensing the air before them, is both a known and adequate cause of an intense light and heat. A combustible body falling into the atmosphere, under such circumstances, would become speedily ignited, but could not burn freely, until it became enveloped in air of greater density; but, on reaching the lower portions of the atmosphere, it would burn with great rapidity.

In the seventh place, some of the larger meteors must have been bodies of great size. According to the testimony of various individuals, in different parts of the United States, a few fire-balls appeared as large as the full moon. Dr. Smith, (then of North Carolina, but since surgeon-general of the Texan army,) who was traveling all night on professional business, describes one which he saw in the following terms: "In size it appeared somewhat larger than the full moon rising. I was startled by the splendid light in which the surrounding scene was exhibited, rendering even small objects quite visible; but I heard no noise, although every sense seemed to be suddenly aroused, in sympathy with the violent impression on the sight." This description implies not only that the body was very large, but that it was at a considerable distance from the spectator. Its actual size will depend upon the distance; for, as it appeared under the same angle as the moon, its diameter will bear the same ratio to the moon's, as its distance bears to the moon's distance. We could, therefore, easily ascertain how large it was, provided we could find how far it was from the observer. If it was one hundred and ten miles distant, its diameter was one mile, and in the same proportion for a greater or less distance; and, if only at the distance of one mile, its diameter was forty-eight feet. For a moderate estimate, we will suppose it to have been twenty-two miles off; then its diameter was eleven hundred and fifty-six feet. Upon every view of the case, therefore, it must be admitted, that these were bodies of great size, compared with other objects which traverse the atmosphere. We may further infer the great magnitude of some of the meteors, from the dimensions of the trains, or clouds, which resulted from their destruction. These often extended over several degrees, and at length were borne along in the direction of the wind, exactly in the manner of a small cloud.

It was an interesting problem to ascertain, if possible, the height above the earth at which these fire-balls exploded, or resolved themselves into a cloud of smoke. This would be an easy task, provided we could be certain that two or more distant observers could be sure that both saw the same meteor; for as each would refer the place of explosion, or the position of the cloud that resulted from it, to a different point of the sky, a parallax would thus be obtained, from which the height might be determined. The large meteor which is mentioned in my account of the shower, (see page 348,) as having exploded near the star Capella, was so peculiar in its appearance, and in the form and motions of the small cloud which resulted from its combustion, that it was noticed and distinguished by a number of observers in distant parts of the country. All described the meteor as exhibiting, substantially, the same peculiarities of appearance; all agreed very nearly in the time of its occurrence; and, on drawing lines, to represent the course and direction of the place where it exploded to the view of each of the observers respectively, these lines met in nearly one and the same point, and that was over the place where it was seen in the zenith. Little doubt, therefore, could remain, that all saw the same body; and on ascertaining, from a comparison of their observations, the amount of parallax, and thence deducing its height,—a task which was ably executed by Professor Twining,—the following results were obtained: that this meteor, and probably all the meteors, entered the atmosphere with a velocity not less, but perhaps greater, than fourteen miles in a second; that they became luminous many miles from the earth,—in this case, over eighty miles; and became extinct high above the surface,—in this case, nearly thirty miles.

In the eighth place, the meteors were combustible bodies, and were constituted of light and transparent materials. The fact that they burned is sufficient proof that they belonged to the class of combustible bodies; and they must have been composed of very light materials, otherwise their momentum would have been sufficient to enable them to make their way through the atmosphere to the surface of the earth. To compare great things with small, we may liken them to a wad discharged from a piece of artillery, its velocity being supposed to be increased (as it may be) to such a degree, that it shall take fire as it moves through the air. Although it would force its way to a great distance from the gun, yet, if not consumed too soon, it would at length be stopped by the resistance of the air. Although it is supposed that the meteors did in fact slightly disturb the atmospheric equilibrium, yet, had they been constituted of dense matter, like meteoric stones, they would doubtless have disturbed it vastly more. Their own momentum would be lost only as it was imparted to the air; and had such a number of bodies,—some of them quite large, perhaps a mile in diameter, and entering the atmosphere with a velocity more than forty times the greatest velocity of a cannon ball,—had they been composed of dense, ponderous[359] matter, we should have had appalling evidence of this fact, not only in the violent winds which they would have produced in the atmosphere, but in the calamities they would have occasioned on the surface of the earth. The meteors were transparent bodies; otherwise, we cannot conceive why the body from which they emanated was not distinctly visible, at least by reflecting the light of the sun. If only the meteors which were known to fall towards the earth had been collected and restored to their original connexion in space, they would have composed a body of great extent; and we cannot imagine a body of such dimensions, under such circumstances, which would not be visible, unless formed of highly transparent materials. By these unavoidable inferences respecting the kind of matter of which the meteors were composed, we are unexpectedly led to recognise a body bearing, in its constitution, a strong analogy to comets, which are also composed of exceedingly light and transparent, and, as there is much reason to believe, of combustible matter.

We now arrive at the final inquiry, what relations did the body which afforded the meteoric shower sustain to the earth? Was it of the nature of a satellite, or terrestrial comet, that revolves around the earth as its centre of motion? Was it a collection of nebulous, or cometary matter, which the earth encountered in its annual progress? or was it a comet, which chanced at this time to be pursuing its path along with the earth, around their common centre of motion? It could not have been of the nature of a satellite to the earth, (or one of those bodies which are held by some to afford the meteoric stones, which sometimes fall to the earth from huge meteors that traverse the atmosphere,) because it remained so long stationary with respect to the earth. A body so near the earth as meteors of this class are known to be, could not remain apparently stationary among the stars for a moment; whereas the body in question occupied the same position, with[360] hardly any perceptible variation, for at least two hours. Nor can we suppose that the earth, in its annual progress, came into the vicinity of a nebula, which was either stationary, or wandering lawless through space. Such a collection of matter could not remain stationary within the solar system, in an insulated state, for, if not prevented by a motion of its own, or by the attraction of some nearer body, it would have proceeded directly towards the sun; and had it been in motion in any other direction than that in which the earth was moving, it would soon have been separated from the earth; since, during the eight hours, while the meteoric shower was visible, the earth moved in its orbit through the space of nearly five hundred and fifty thousand miles.

The foregoing considerations conduct us to the following train of reasoning. First, if all the meteors which fell on the morning of November 13, 1833, had been collected and restored to their original connexion in space, they would of themselves have constituted a nebulous body of great extent; but we have reason to suppose that they, in fact, composed but a small part of the mass from which they emanated, since, after the loss of so much matter as proceeded from it in the great meteoric shower of 1799, and in the several repetitions of it that preceded the year 1833, it was still capable of affording so copious a shower on that year; and similar showers, more limited in extent, were repeated for at least five years afterwards. We are therefore to regard the part that descended only as the extreme portions of a body or collection of meteors, of unknown extent, existing in the planetary spaces.

Secondly, since the earth fell in with this body in the same part of its orbit, for several years in succession, it must either have remained there while the earth was performing its whole revolution around the sun, or it must itself have had a revolution, as well as the earth. But I have already shown that it could not have remained stationary in that part of space; therefore, it must have had a revolution around the sun.[361]

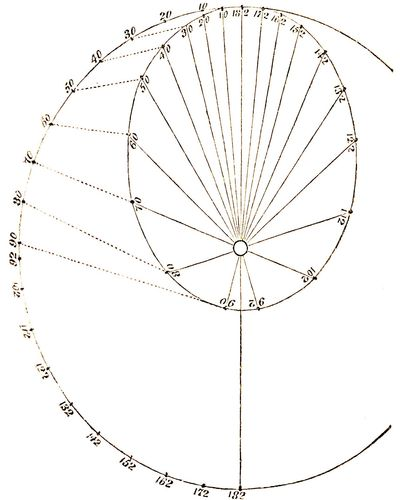

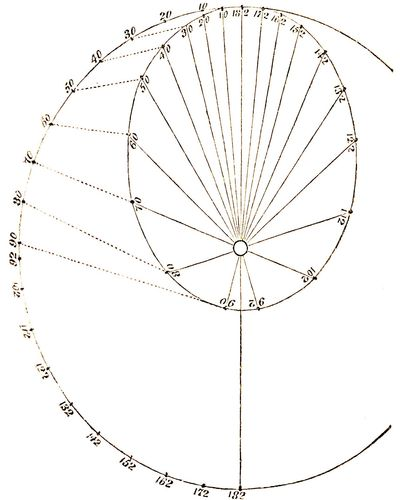

Thirdly, its period of revolution must have either been greater than the earth's, equal to it, or less. It could not have been greater, for then the two bodies could not have been together again at the end of the year, since the meteoric body would not have completed its revolution in a year. Its period might obviously be the same as the earth's, for then they might easily come together again after one revolution of each; although their orbits might differ so much in shape as to prevent their being together at any intermediate point. But the period of the body might also be less than that of the earth, provided it were some aliquot part of a year, so as to revolve just twice, or three times, for example, while the earth revolves once. Let us suppose that the period is one third of a year. Then, since we have given the periodic times of the two bodies, and the major axis of the orbit of one of them, namely, of the earth, we can, by Kepler's law, find the major axis of the other orbit; for the square of the earth's periodic time 12 is to the square of the body's time (1⁄3)2 as the cube of the major axis of the earth's orbit is to the cube of the major axis of the orbit in question. Now, the three first terms of this proportion are known, and consequently, it is only to solve a case in the simple rule of three, to find the term required. On making the calculation, it is found, that the supposition of a periodic time of only one third of a year gives an orbit of insufficient length; the whole major axis would not reach from the sun to the earth; and consequently, a body revolving in it could never come near to the earth. On making trial of six months, we obtain an orbit which satisfies the conditions, being such as is represented by the diagram on page 362, Fig. 69´, where the outer circle denotes the earth's orbit, the sun being in the centre, and the inner ellipse denotes the path of the meteoric body. The two bodies are together at the top of the figure, being the place of the meteoric body's aphelion on the thirteenth of November, and the figures 10, 20, &c., denote the relative positions[362] of the earth and the body for every ten days, for a period of six months, in which time the body would have returned to its aphelion.

Fig. 69´.

Such would be the relation of the body that affords the meteoric shower of November, provided its revolution is accomplished in six months; but it is still somewhat uncertain whether the period be half a year or a year; it must be one or the other.

If we inquire, now, why the meteors always appear to radiate from a point in the constellation Leo, recollecting that this is the point to which the body is projected among the stars, the answer is, that this is the very point towards which the earth is moving in her orbit at that time; so that if, as we have proved, the earth passed through or near a nebulous body on the thirteenth of November, that body must necessarily have been projected into the constellation Leo, else it could not have lain directly in her path. I consider it therefore as established by satisfactory proof, that the meteors of November thirteenth emanate from a nebulous or cometary body, revolving around the sun, and coming so near the earth at that time that the earth passes through its skirts, or extreme portions, and thus attracts to itself some portions of its matter, giving to the meteors a greater velocity than could be imparted by gravity alone, in consequence of passing rapidly by them.

All these conclusions were made out by a process of reasoning strictly inductive, without supposing that the meteoric body itself had ever been seen. But there are some reasons for believing that we do actually see it, and that it is no other than that mysterious appearance long known under the name of the zodiacal light. This is a faint light, which at certain seasons of the year appears in the west after evening twilight, and at certain other seasons appears in the east before the dawn, following or preceding the track of the sun in a triangular figure, with its broad base next to the sun, and its vertex reaching to a greater or less distance, sometimes more than ninety degrees from that luminary. You may obtain a good view of it in February or March, in the west, or in October, in the morning sky. The various changes which this light undergoes at different seasons of the year are such as to render it probable, to my mind, that this is the very body which affords the meteoric showers; its extremity coming, in November, within the sphere of the earth's attraction. But, as the arguments for the existence of a body in the planetary regions, which affords these showers, were drawn without the least reference to the zodiacal light,[364] and are good, should it finally be proved that this light has no connection with them, I will not occupy your attention with the discussion of this point, to the exclusion of topics which will probably interest you more.

It is perhaps most probable, that the meteoric showers of August and December emanate from the same body. I know of nothing repugnant to this conclusion, although it has not yet been distinctly made out. Had the periods of the earth and of the meteoric body been so adjusted to each other that the latter was contained an exact even number of times in the former; that is, had it been exactly either a year or half a year; then we might expect a similar recurrence of the meteoric shower every year; but only a slight variation in such a proportion between the two periods would occasion the repetition of the shower for a few years in succession, and then an intermission of them, for an unknown length of time, until the two bodies were brought into the same relative situation as before. Disturbances, also, occasioned by the action of Venus and Mercury, might wholly subvert this numerical relation, and increase or diminish the probability of a repetition of the phenomenon. Accordingly, from the year 1830, when the meteoric shower of November was first observed, until 1833, there was a regular increase of the exhibition; in 1833, it came to its maximum; and after that time it was repeated upon a constantly diminishing scale, until 1838, since which time it has not been observed. Perhaps ages may roll away before the world will be again surprised and delighted with a display of celestial fire-works equal to that of the morning of November 13, 1833.

November 13, 1833

Giving an insight into thoughts and feelings of witnesses at the time are the following description of the Wall family’s experience as written by Bruna McGuire and Betty Wall:

“The stars showered down so thickly and fast that it looked as though every star in the heavens was falling. When they touched the ground, they burst and drifted away. Stars were still falling when the Sun arose the next morning. Never before had there been such a sight witnessed, nor has there been since the greatest meteoric display of our age.”

Astronomer Denison Olmsted Gave a much longer explanation, gathering information from newspapers from all over North America: "LETTER XXVII. - METEORIC SHOWERS."

"Oft shalt thou see, ere brooding storms arise, Star after star glide headlong down the skies, And, where they shot, long trails of lingering light Sweep far behind, and gild the shades of night."—Virgil.

Few subjects of astronomy have excited a more general interest, for several years past, than those extraordinary exhibitions of shooting stars, which have acquired the name of meteoric showers. My reason for introducing the subject to your notice, in this place, is, that these small bodies are, as I believe, derived from nebulous or cometary bodies, which belong to the solar system, and which, therefore, ought to be considered, before we take our leave of this department of creation, and naturally come next in order to comets.

The attention of astronomers was particularly directed to this subject by the extraordinary shower of meteors which occurred on the morning of the thirteenth of November, 1833. I had the good fortune to witness these grand celestial fire-works, and felt a strong desire that a phenomenon, which, as it afterwards appeared, was confined chiefly to North America, should here command that diligent inquiry into its causes, which so sublime a spectacle might justly claim.

As I think you were not so happy as to witness this magnificent display, I will endeavor to give you some faint idea of it, as it appeared to me a little before daybreak. Imagine a constant succession of fire-balls, resembling sky-rockets, radiating in all directions from a point in the heavens a few degrees southeast of the zenith, and following the arch of the sky towards the horizon. They commenced their progress at different distances from the radiating point; but their directions were uniformly such, that the lines they described, if produced upwards, would all have met in the same part of the heavens. Around this point, or imaginary radiant, was a circular space of several degrees, within which no meteors were observed. The balls, as they traveled down the vault, usually left after them a vivid streak of light; and, just before they disappeared, exploded, or suddenly resolved themselves into smoke. No report of any kind was observed, although we listened attentively.

Beside the foregoing distinct concretions, or individual bodies, the atmosphere exhibited phosphoric lines, following in the train of minute points, that shot off in the greatest abundance in a northwesterly direction. These did not so fully copy the figure of the sky, but moved in paths more nearly rectilinear, and appeared to be much nearer the spectator than the fire-balls. The light of their trains was also of a paler hue, not unlike that produced by writing with a stick of phosphorus on the walls of a dark room. The number of these luminous trains increased and diminished alternately, now and then crossing the field of view, like snow drifted before the wind, although, in fact, their course was towards the wind.

From these two varieties, we were presented with meteors of various sizes and degrees of splendor: some were mere points, while others were larger and brighter than Jupiter or Venus; and one, seen by a credible witness, at an earlier hour, was judged to be nearly as large as the moon. The flashes of light, although less intense than lightning, were so bright, as to awaken people in their beds. One ball that shot off in the northwest direction, and exploded a little northward of[348] the star Capella, left, just behind the place of explosion, a phosphorescent train of peculiar beauty. This train was at first nearly straight, but it shortly began to contract in length, to dilate in breadth, and to assume the figure of a serpent drawing itself up, until it appeared like a small luminous cloud of vapor. This cloud was borne eastward, (by the wind, as was supposed, which was blowing gently in that direction,) opposite to the direction in which the meteor itself had moved, remaining in sight several minutes. The point from which the meteors seemed to radiate kept a fixed position among the stars, being constantly near a star in Leo, called Gamma Leonis.

Such is a brief description of this grand and beautiful display, as I saw it at New Haven. The newspapers shortly brought us intelligence of similar appearances in all parts of the United States, and many minute descriptions were published by various observers; from which it appeared, that the exhibition had been marked by very nearly the same characteristics wherever it had been seen. Probably no celestial phenomenon has ever occurred in this country, since its first settlement, which was viewed with so much admiration and delight by one class of spectators, or with so much astonishment and fear by another class. It strikingly evinced the progress of knowledge and civilization, that the latter class was comparatively so small, although it afforded some few examples of the dismay with which, in barbarous ages of the world, such spectacles as this were wont to be regarded. One or two instances were reported, of persons who died with terror; many others thought the last great day had come; and the untutored black population of the South gave expression to their fears in cries and shrieks.

After collecting and collating the accounts given in all the periodicals of the country, and also in numerous letters addressed either to my scientific friends or to myself, the following appeared to be the leading facts attending the phenomenon. The shower pervaded nearly the whole of North America, having appeared in nearly equal splendor from the British possessions on the north to the West-India Islands and Mexico on the south, and from sixty-one degrees of longitude east of the American coast, quite to the Pacific Ocean on the west. Throughout this immense region, the duration was nearly the same. The meteors began to attract attention by their unusual frequency and brilliancy, from nine to twelve o'clock in the evening; were most striking in their appearance from two to five; arrived at their maximum, in many places, about four o'clock; and continued until rendered invisible by the light of day. The meteors moved either in right lines, or in such apparent curves, as, upon optical principles, can be resolved into right lines. Their general tendency was towards the northwest, although, by the effect of perspective, they appeared to move in various directions.

Such were the leading phenomena of the great meteoric shower of November 13, 1833. For a fuller detail of the facts, as well as of the reasoning's that were built on them, I must beg leave to refer you to some papers of mine in the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth volumes of the American Journal of Science.

Soon after this wonderful occurrence, it was ascertained that a similar meteoric shower had appeared in 1799, and, what was remarkable, almost at exactly the same time of year, namely, on the morning of the twelfth of November; and we were again surprised as well as delighted, at receiving successive accounts from different parts of the world of the phenomenon, as having occurred on the morning of the same thirteenth of November, in 1830, 1831, and 1832. Hence this was evidently an event independent of the casual changes of the atmosphere; for, having a periodical return, it was undoubtedly to be referred to astronomical causes, and its recurrence, at a certain definite period of the year, plainly indicated some relation to the revolution of the earth around the sun. It remained, however, to develop the nature of this relation, by investigating, if possible, the origin of the meteors. The views to which I was led on this subject suggested the probability that the same phenomenon would recur on the corresponding seasons of the year, for at least several years afterwards; and such proved to be the fact, although the appearances, at every succeeding return, were less and less striking, until 1839, when, so far as I have heard, they ceased altogether.

Mean-while, two other distinct periods of meteoric showers have, as already intimated, been determined; namely, about the ninth of August, and seventh of December. The facts relative to the history of these periods have been collected with great industry by Mr. Edward C. Herrick; and several of the most ingenious and most useful conclusions, respecting the laws that regulate these singular exhibitions, have been deduced by Professor Twining. Several of the most distinguished astronomers of the Old World, also, have engaged in these investigations with great zeal, as Messrs. Arago and Biot, of Paris; Doctor Olbers, of Bremen; M. Wartmann, of Geneva; and M. Quetelet, of Brussels.

But you will be desirous to learn what are the conclusions which have been drawn respecting these new and extraordinary phenomena of the heavens. As the inferences to which I was led, as explained in the twenty-sixth volume of the 'American Journal of Science,' have, at least in their most important points, been sanctioned by astronomers of the highest respectability, I will venture to give you a brief abstract of them, with such modifications as the progress of investigation since that period has rendered necessary.

The principal questions involved in the inquiry were the following:—Was the origin of the meteors within the atmosphere, or beyond it? What was the height of the place above the surface of the earth? By what force were the meteors drawn or impelled towards the earth? In what directions did they move? With what velocity? What was the cause of their light and[351] heat? Of what size were the larger varieties? At what height above the earth did they disappear? What was the nature of the luminous trains which sometimes remained behind? What sort of bodies were the meteors themselves; of what kind of matter constituted; and in what manner did they exist before they fell to the earth? Finally, what relations did the source from which they emanated sustain to our earth?

In the first place, the meteors had their origin beyond the limits of our atmosphere. We know whether a given appearance in the sky is within the atmosphere or beyond it, by this circumstance: all bodies near the earth, including the atmosphere itself, have a common motion with the earth around its axis from west to east. When we see a celestial object moving regularly from west to east, at the same rate as the earth moves, leaving the stars behind, we know it is near the earth, and partakes, in common with the atmosphere, of its diurnal rotation: but when the earth leaves the object behind; or, in other words, when the object moves westward along with the stars, then we know that it is so distant as not to participate in the diurnal revolution of the earth, and of course to be beyond the atmosphere. The source from which the meteors emanated thus kept pace with the stars, and hence was beyond the atmosphere.

In the second place, the height of the place whence the meteors proceeded was very great, but it has not yet been accurately determined. Regarding the body whence the meteors emanated after the similitude of a cloud, it seemed possible to obtain its height in the same manner as we measure the height of a cloud, or indeed the height of the moon. Although we could not see the body itself, yet the part of the heavens whence the meteors came would indicate its position. This point we called the radiant; and the question was, whether the radiant was projected by distant observers on different parts of the sky; that is, whether it had any parallax. I took much pains to ascertain the truth of this matter, by corresponding with various[352] observers in different parts of the United States, who had accurately noted the position of the radiant among the fixed stars, and supposed I had obtained such materials as would enable us to determine the parallax, at least approximately; although such discordance existed in the evidence as reasonably to create some distrust of its validity. Putting together, however, the best materials I could obtain, I made the height of the radiant above the surface of the earth twenty-two hundred and thirty-eight miles. When, however, I afterwards obtained, as I supposed, some insight into the celestial origin of the meteors, I at once saw that the meteoric body must be much further off than this distance; and my present impression is, that we have not the means of determining what its height really is. We may safely place it at many thousand miles.

In the third place, with respect to the force by which the meteors were drawn or impelled towards the earth, my first impression was, that they fell merely by the force of gravity; but the velocity which, on careful investigation by Professor Twining and others, has been ascribed to them, is greater than can possibly result from gravity, since a body can never acquire, by gravity alone, a velocity greater than about seven miles per second. Some other cause, beside gravity, must therefore act, in order to give the meteors so great an apparent velocity.

In the fourth place, the meteors fell towards the earth in straight lines, and in directions which, within considerable distances, were nearly parallel with each other. The courses are inferred to have been in straight lines, because no others could have appeared to spectators in different situations to have described arcs of great circles. In order to be projected into the arc of a great circle, the line of descent must be in a plane passing through the eye of the spectator; and the intersection of such planes, passing through the eyes of different spectators, must be straight lines. The lines of direction are inferred to have been parallel, on account of their apparent radiation from one point, that[353] being the vanishing point of parallel lines. This may appear to you a little paradoxical, to infer that lines are parallel, because they diverge from one and the same point; but it is a well-known principle of perspective, that parallel lines, when continued to a great distance from the eye, appear to converge towards the remoter end. You may observe this in two long rows of trees, or of street lamps.

Fig. 69.

Some idea of the manner in which the meteors fell, and of the reason of their apparent radiation from a common point, may be gathered from the annexed diagram. Let A B C, Fig. 69, represent the vault of the sky, the center of which, D, being the place of the spectator. Let 1, 2, 3, &c., represent parallel lines directed towards the earth. A luminous body descending through 1´ 1, coinciding with the line D E, coincident with the axis of vision, (or the line drawn from the meteoric body to the eye,) would appear stationary all the while at 1´, because distant bodies always appear stationary when they are moving either directly towards us or directly from us. A body descending through 2 2, would seem to describe the short arc 2´ 2´, appearing to move on the concave of the sky between the lines drawn from the eye to the two extremities of its line of motion; and, for a similar reason, a body descending through 3 3, would appear to describe the larger arc 3´ 3´. Hence, those meteors which fell nearer to the axis of vision, would describe shorter arcs, and move slower, while those which were further from the axis and nearer the horizon would appear to describe longer arcs, and to move with greater velocity; the meteors would all seem to radiate from a common center, namely, the point where the axis of vision met the celestial vault; and if any meteor chanced to move directly in the line of vision, it would be seen as a luminous body, stationary, for a few seconds, at the center of radiation. To see how exactly the facts, as observed, corresponded to these inferences, derived from the supposition that the meteors moved in parallel lines, take the following description, as given immediately after the occurrence, by Professor Twining. "In the vicinity of the radiant point, a few star-like bodies were observed, possessing very little motion, and leaving very little length of trace. Further off, the motions were more rapid and the traces longer; and most rapid of all, and longest in their traces, were those which originated but a few degrees above the horizon, and descended down to it."

In the fifth place, had the meteors come from a point twenty-two hundred and thirty-eight miles from the earth, and derived their apparent velocity from gravity[355] alone, then it would be found, by a very easy calculation, that their actual velocity was about four miles per second; but, as already intimated, the velocity observed was estimated much greater than could be accounted for on these principles; not less, indeed, than fourteen miles per second, and, in some instances, much greater even than this. The motion of the earth in its orbit is about nineteen miles per second; and the most reasonable supposition we can make, at present, to account for the great velocity of the meteors, is, that they derived a relative motion from the earth's passing rapidly by them,—a supposition which is countenanced by the fact that they generally tended westward contrary to the earth's motion in its orbit.

In the sixth place, the meteors consisted of combustible matter, and took fire, and were consumed, in traversing the atmosphere. That these bodies underwent combustion, we had the direct evidence of the senses, inasmuch as we saw them burn. That they took fire in the atmosphere, was inferred from the fact that they were not luminous in their original situations in space, otherwise, we should have seen the body from which they emanated; and had they been luminous before reaching the atmosphere, we should have seen them for a much longer period than they were in sight, as they must have occupied a considerable time in descending towards the earth from so great a distance, even at the rapid rate at which they traveled. The immediate consequence of the prodigious velocity with which the meteors fell into the atmosphere must be a powerful condensation of the air before them, retarding their progress, and producing, by a sudden compression of the air, a great evolution of heat. There is a little instrument called the air-match, consisting of a piston and cylinder, like a syringe, in which we strike a light by suddenly forcing down the piston upon the air below. As the air cannot escape, it is suddenly compressed, and gives a spark sufficient to light a piece of tinder at the bottom of the cylinder. Indeed, it is a well[356]-known fact, that, whenever air is suddenly and forcibly compressed, heat is elicited; and, if by such a compression as may be given by the hand in the air-match, heat is evolved sufficient to fire tinder, what must be the heat evolved by the motion of a large body in the atmosphere, with a velocity so immense. It is common to resort to electricity as the agent which produces the heat and light of shooting stars; but even were electricity competent to produce this effect, its presence, in the case before us, is not proved; and its agency is unnecessary, since so swift a motion of the meteors themselves, suddenly condensing the air before them, is both a known and adequate cause of an intense light and heat. A combustible body falling into the atmosphere, under such circumstances, would become speedily ignited, but could not burn freely, until it became enveloped in air of greater density; but, on reaching the lower portions of the atmosphere, it would burn with great rapidity.

In the seventh place, some of the larger meteors must have been bodies of great size. According to the testimony of various individuals, in different parts of the United States, a few fire-balls appeared as large as the full moon. Dr. Smith, (then of North Carolina, but since surgeon-general of the Texan army,) who was traveling all night on professional business, describes one which he saw in the following terms: "In size it appeared somewhat larger than the full moon rising. I was startled by the splendid light in which the surrounding scene was exhibited, rendering even small objects quite visible; but I heard no noise, although every sense seemed to be suddenly aroused, in sympathy with the violent impression on the sight." This description implies not only that the body was very large, but that it was at a considerable distance from the spectator. Its actual size will depend upon the distance; for, as it appeared under the same angle as the moon, its diameter will bear the same ratio to the moon's, as its distance bears to the moon's distance. We could, therefore, easily ascertain how large it was, provided we could find how far it was from the observer. If it was one hundred and ten miles distant, its diameter was one mile, and in the same proportion for a greater or less distance; and, if only at the distance of one mile, its diameter was forty-eight feet. For a moderate estimate, we will suppose it to have been twenty-two miles off; then its diameter was eleven hundred and fifty-six feet. Upon every view of the case, therefore, it must be admitted, that these were bodies of great size, compared with other objects which traverse the atmosphere. We may further infer the great magnitude of some of the meteors, from the dimensions of the trains, or clouds, which resulted from their destruction. These often extended over several degrees, and at length were borne along in the direction of the wind, exactly in the manner of a small cloud.

It was an interesting problem to ascertain, if possible, the height above the earth at which these fire-balls exploded, or resolved themselves into a cloud of smoke. This would be an easy task, provided we could be certain that two or more distant observers could be sure that both saw the same meteor; for as each would refer the place of explosion, or the position of the cloud that resulted from it, to a different point of the sky, a parallax would thus be obtained, from which the height might be determined. The large meteor which is mentioned in my account of the shower, (see page 348,) as having exploded near the star Capella, was so peculiar in its appearance, and in the form and motions of the small cloud which resulted from its combustion, that it was noticed and distinguished by a number of observers in distant parts of the country. All described the meteor as exhibiting, substantially, the same peculiarities of appearance; all agreed very nearly in the time of its occurrence; and, on drawing lines, to represent the course and direction of the place where it exploded to the view of each of the observers respectively, these lines met in nearly one and the same point, and that was over the place where it was seen in the zenith. Little doubt, therefore, could remain, that all saw the same body; and on ascertaining, from a comparison of their observations, the amount of parallax, and thence deducing its height,—a task which was ably executed by Professor Twining,—the following results were obtained: that this meteor, and probably all the meteors, entered the atmosphere with a velocity not less, but perhaps greater, than fourteen miles in a second; that they became luminous many miles from the earth,—in this case, over eighty miles; and became extinct high above the surface,—in this case, nearly thirty miles.

In the eighth place, the meteors were combustible bodies, and were constituted of light and transparent materials. The fact that they burned is sufficient proof that they belonged to the class of combustible bodies; and they must have been composed of very light materials, otherwise their momentum would have been sufficient to enable them to make their way through the atmosphere to the surface of the earth. To compare great things with small, we may liken them to a wad discharged from a piece of artillery, its velocity being supposed to be increased (as it may be) to such a degree, that it shall take fire as it moves through the air. Although it would force its way to a great distance from the gun, yet, if not consumed too soon, it would at length be stopped by the resistance of the air. Although it is supposed that the meteors did in fact slightly disturb the atmospheric equilibrium, yet, had they been constituted of dense matter, like meteoric stones, they would doubtless have disturbed it vastly more. Their own momentum would be lost only as it was imparted to the air; and had such a number of bodies,—some of them quite large, perhaps a mile in diameter, and entering the atmosphere with a velocity more than forty times the greatest velocity of a cannon ball,—had they been composed of dense, ponderous[359] matter, we should have had appalling evidence of this fact, not only in the violent winds which they would have produced in the atmosphere, but in the calamities they would have occasioned on the surface of the earth. The meteors were transparent bodies; otherwise, we cannot conceive why the body from which they emanated was not distinctly visible, at least by reflecting the light of the sun. If only the meteors which were known to fall towards the earth had been collected and restored to their original connexion in space, they would have composed a body of great extent; and we cannot imagine a body of such dimensions, under such circumstances, which would not be visible, unless formed of highly transparent materials. By these unavoidable inferences respecting the kind of matter of which the meteors were composed, we are unexpectedly led to recognise a body bearing, in its constitution, a strong analogy to comets, which are also composed of exceedingly light and transparent, and, as there is much reason to believe, of combustible matter.

We now arrive at the final inquiry, what relations did the body which afforded the meteoric shower sustain to the earth? Was it of the nature of a satellite, or terrestrial comet, that revolves around the earth as its centre of motion? Was it a collection of nebulous, or cometary matter, which the earth encountered in its annual progress? or was it a comet, which chanced at this time to be pursuing its path along with the earth, around their common centre of motion? It could not have been of the nature of a satellite to the earth, (or one of those bodies which are held by some to afford the meteoric stones, which sometimes fall to the earth from huge meteors that traverse the atmosphere,) because it remained so long stationary with respect to the earth. A body so near the earth as meteors of this class are known to be, could not remain apparently stationary among the stars for a moment; whereas the body in question occupied the same position, with[360] hardly any perceptible variation, for at least two hours. Nor can we suppose that the earth, in its annual progress, came into the vicinity of a nebula, which was either stationary, or wandering lawless through space. Such a collection of matter could not remain stationary within the solar system, in an insulated state, for, if not prevented by a motion of its own, or by the attraction of some nearer body, it would have proceeded directly towards the sun; and had it been in motion in any other direction than that in which the earth was moving, it would soon have been separated from the earth; since, during the eight hours, while the meteoric shower was visible, the earth moved in its orbit through the space of nearly five hundred and fifty thousand miles.

The foregoing considerations conduct us to the following train of reasoning. First, if all the meteors which fell on the morning of November 13, 1833, had been collected and restored to their original connexion in space, they would of themselves have constituted a nebulous body of great extent; but we have reason to suppose that they, in fact, composed but a small part of the mass from which they emanated, since, after the loss of so much matter as proceeded from it in the great meteoric shower of 1799, and in the several repetitions of it that preceded the year 1833, it was still capable of affording so copious a shower on that year; and similar showers, more limited in extent, were repeated for at least five years afterwards. We are therefore to regard the part that descended only as the extreme portions of a body or collection of meteors, of unknown extent, existing in the planetary spaces.

Secondly, since the earth fell in with this body in the same part of its orbit, for several years in succession, it must either have remained there while the earth was performing its whole revolution around the sun, or it must itself have had a revolution, as well as the earth. But I have already shown that it could not have remained stationary in that part of space; therefore, it must have had a revolution around the sun.[361]

Thirdly, its period of revolution must have either been greater than the earth's, equal to it, or less. It could not have been greater, for then the two bodies could not have been together again at the end of the year, since the meteoric body would not have completed its revolution in a year. Its period might obviously be the same as the earth's, for then they might easily come together again after one revolution of each; although their orbits might differ so much in shape as to prevent their being together at any intermediate point. But the period of the body might also be less than that of the earth, provided it were some aliquot part of a year, so as to revolve just twice, or three times, for example, while the earth revolves once. Let us suppose that the period is one third of a year. Then, since we have given the periodic times of the two bodies, and the major axis of the orbit of one of them, namely, of the earth, we can, by Kepler's law, find the major axis of the other orbit; for the square of the earth's periodic time 12 is to the square of the body's time (1⁄3)2 as the cube of the major axis of the earth's orbit is to the cube of the major axis of the orbit in question. Now, the three first terms of this proportion are known, and consequently, it is only to solve a case in the simple rule of three, to find the term required. On making the calculation, it is found, that the supposition of a periodic time of only one third of a year gives an orbit of insufficient length; the whole major axis would not reach from the sun to the earth; and consequently, a body revolving in it could never come near to the earth. On making trial of six months, we obtain an orbit which satisfies the conditions, being such as is represented by the diagram on page 362, Fig. 69´, where the outer circle denotes the earth's orbit, the sun being in the centre, and the inner ellipse denotes the path of the meteoric body. The two bodies are together at the top of the figure, being the place of the meteoric body's aphelion on the thirteenth of November, and the figures 10, 20, &c., denote the relative positions[362] of the earth and the body for every ten days, for a period of six months, in which time the body would have returned to its aphelion.

Fig. 69´.

Such would be the relation of the body that affords the meteoric shower of November, provided its revolution is accomplished in six months; but it is still somewhat uncertain whether the period be half a year or a year; it must be one or the other.

If we inquire, now, why the meteors always appear to radiate from a point in the constellation Leo, recollecting that this is the point to which the body is projected among the stars, the answer is, that this is the very point towards which the earth is moving in her orbit at that time; so that if, as we have proved, the earth passed through or near a nebulous body on the thirteenth of November, that body must necessarily have been projected into the constellation Leo, else it could not have lain directly in her path. I consider it therefore as established by satisfactory proof, that the meteors of November thirteenth emanate from a nebulous or cometary body, revolving around the sun, and coming so near the earth at that time that the earth passes through its skirts, or extreme portions, and thus attracts to itself some portions of its matter, giving to the meteors a greater velocity than could be imparted by gravity alone, in consequence of passing rapidly by them.

All these conclusions were made out by a process of reasoning strictly inductive, without supposing that the meteoric body itself had ever been seen. But there are some reasons for believing that we do actually see it, and that it is no other than that mysterious appearance long known under the name of the zodiacal light. This is a faint light, which at certain seasons of the year appears in the west after evening twilight, and at certain other seasons appears in the east before the dawn, following or preceding the track of the sun in a triangular figure, with its broad base next to the sun, and its vertex reaching to a greater or less distance, sometimes more than ninety degrees from that luminary. You may obtain a good view of it in February or March, in the west, or in October, in the morning sky. The various changes which this light undergoes at different seasons of the year are such as to render it probable, to my mind, that this is the very body which affords the meteoric showers; its extremity coming, in November, within the sphere of the earth's attraction. But, as the arguments for the existence of a body in the planetary regions, which affords these showers, were drawn without the least reference to the zodiacal light,[364] and are good, should it finally be proved that this light has no connection with them, I will not occupy your attention with the discussion of this point, to the exclusion of topics which will probably interest you more.

It is perhaps most probable, that the meteoric showers of August and December emanate from the same body. I know of nothing repugnant to this conclusion, although it has not yet been distinctly made out. Had the periods of the earth and of the meteoric body been so adjusted to each other that the latter was contained an exact even number of times in the former; that is, had it been exactly either a year or half a year; then we might expect a similar recurrence of the meteoric shower every year; but only a slight variation in such a proportion between the two periods would occasion the repetition of the shower for a few years in succession, and then an intermission of them, for an unknown length of time, until the two bodies were brought into the same relative situation as before. Disturbances, also, occasioned by the action of Venus and Mercury, might wholly subvert this numerical relation, and increase or diminish the probability of a repetition of the phenomenon. Accordingly, from the year 1830, when the meteoric shower of November was first observed, until 1833, there was a regular increase of the exhibition; in 1833, it came to its maximum; and after that time it was repeated upon a constantly diminishing scale, until 1838, since which time it has not been observed. Perhaps ages may roll away before the world will be again surprised and delighted with a display of celestial fire-works equal to that of the morning of November 13, 1833.

... to the New Guys from The ChatBox V.2 Crew

... to the New Guys from The ChatBox V.2 Crew