Post by 1dave on Feb 12, 2014 13:07:58 GMT -5

I posted this in the Cabochon section, but it applies to metals too.

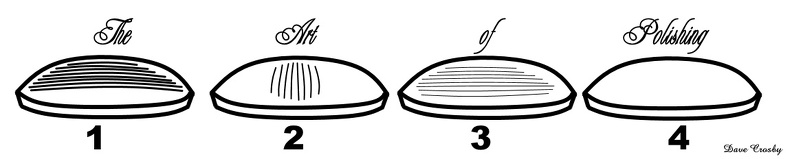

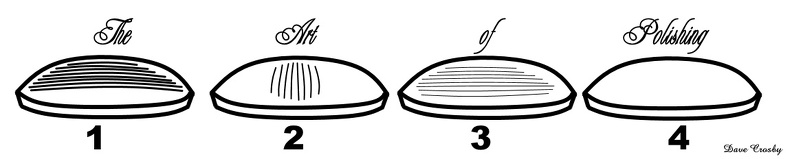

A. There are two paths to a polished finish.

1. Re-grinding the surface with ever finer abrasives (rotate 90 degrees each time for easier viewing) until the last scratches are so fine they can no longer be seen.

2. The Beilby Layer.

Not all materials will respond with the Beilby Layer.

For the softer stones that will, Vinegar can often be a BIG help.

B. Polishing Compounds.

There are many kinds of polishing powders and modifications of them for sale. The latter include bars, sticks, liquids, slurries and other mixtures, often sold under a trade name.

Nearly all polishing powders are mineral oxides, such as rouge (iron oxide), tin oxide, chrome oxide and many others. Occasionally two or more of these are mixed and sold under a trade name. They may be mixed with some cohesive substance and sold as a bar or stick; rouge is a good example. A few have been suspended in an emulsion and sold as slurry.

Black rouge is for gold, silver, and German Silver. It will give a very high polish. Do not press too hard, as it will heat and cause some of the colors on the wonder stones to actually run or blend together. This is true with most all of your polishes on this kind of material.

Green rouge is for polishing platinum, chrome, stainless steel, and hard materials. I have found that it will give a high polish to most of the jade materials that will stand a lot of heat. Try it on a piece of waste first, as it sometimes has a tendency to stain the cab. It is really on green jade or other green-like material.

Red rouge is for gold, silver, and soft metals and materials. It works well on soft buff wheels for a final finish, Try not to put it on too heavily, and you will get a better finish. Use a light touch, and I do not recommend the use of red rouge on soft materials, as it has a tendency to discolor the material, but it is fine for most of the metals.

White rouge is for the harder metals; platinum, chrome, stainless steel, or some of the harder material.

Then, there is the good old zam. It is mildly abrasive. Use with tight-weave muslin wheels for soft stones like turquoise and variscite. It is also good for a nice polish on silver, brass, copper, epoxies and plastics.

Hints: The initial surface should be prepared with a slightly rougher abrasive such as Tripoli.

Avoid surface drag lines on stone, epoxy or plastic by not letting the buff get too hot.

C. Applying the Polishing Compound.

There are many kinds of polishes and different ways to do it, but here are some of the ways that have provided satisfactory results.

LIST FOR YOU TO COPY AND PRINT:

OLD VERSION

A. There are two paths to a polished finish.

1. Re-grinding the surface with ever finer abrasives (rotate 90 degrees each time for easier viewing) until the last scratches are so fine they can no longer be seen.

2. The Beilby Layer.

What is the Beilby layer? It is a phenomenon that brings about a polished surface.

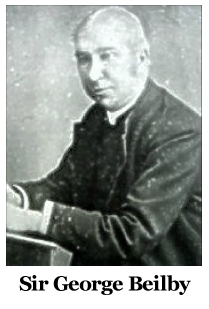

Sir George Beilby (17 November 1850 – 1 August 1924) discovered that during polishing the surface of gemstones actually melted and flowed as a “glassy” layer over very fine scratches. He proved it by noting a certain scratch pattern, polishing the surface, and then recovering the scratch pattern by etching away the polished surface with acids.

In 1937, a Mr. Finch, using another technique, confirmed this finding. He reported that there were two types of polish:

1. the Beilby flow and

2. the surface that has such fine scratches that it appeared polished.

The latter existed on those materials that were unable to flow in the Beilby manner.

The Beilby layer can occur in three ways.

First as an amorphous layer much like glass, e.g., the polish on zircon and spinel.

Second as an amorphous layer, but parallel to crystal planes and crystallizing again in these lines, e.g., calcite.

Third the layer forms by flowing but immediately crystallizes identically to the underlying material, e.g. quartz.

Distinguishing properties of the Beilby layer: It is very thin and usually slightly harder than the underlying material, probably due to packing of molecules by pressure.

There still remains some controversy over the existence of the Beilby Layer.

Some argue that the “flow” is not true melting, but rather a migration of molecules under pressure.

Polish seems to be the result of a combination of temperature, pressure, moisture, polishing agent, and varies from material to material.

But does it really matter, as long as we get a good polish?

Author unknown, from Geolap News, Aug. 1997

Via Chippers Chatter 11/06

Via The RockCollector 11/06

Sir George Beilby (17 November 1850 – 1 August 1924) discovered that during polishing the surface of gemstones actually melted and flowed as a “glassy” layer over very fine scratches. He proved it by noting a certain scratch pattern, polishing the surface, and then recovering the scratch pattern by etching away the polished surface with acids.

In 1937, a Mr. Finch, using another technique, confirmed this finding. He reported that there were two types of polish:

1. the Beilby flow and

2. the surface that has such fine scratches that it appeared polished.

The latter existed on those materials that were unable to flow in the Beilby manner.

The Beilby layer can occur in three ways.

First as an amorphous layer much like glass, e.g., the polish on zircon and spinel.

Second as an amorphous layer, but parallel to crystal planes and crystallizing again in these lines, e.g., calcite.

Third the layer forms by flowing but immediately crystallizes identically to the underlying material, e.g. quartz.

Distinguishing properties of the Beilby layer: It is very thin and usually slightly harder than the underlying material, probably due to packing of molecules by pressure.

There still remains some controversy over the existence of the Beilby Layer.

Some argue that the “flow” is not true melting, but rather a migration of molecules under pressure.

Polish seems to be the result of a combination of temperature, pressure, moisture, polishing agent, and varies from material to material.

But does it really matter, as long as we get a good polish?

Author unknown, from Geolap News, Aug. 1997

Via Chippers Chatter 11/06

Via The RockCollector 11/06

Not all materials will respond with the Beilby Layer.

For the softer stones that will, Vinegar can often be a BIG help.

“Can Vinegar Help Polishing?

Using acid as an assist is polishing is an area that many faceters and cabochon cutters avoid, Too dangerous.

Yes, it can be dangerous. But please remember that plain vinegar contains enough acid to virtually eliminate scratching problems. You’ll be pleasantly gratified at the scratch-eliminating contributions of a bit of vinegar added to either chemical or diamond polish.

Via Rock Chips 7/03"

“Polishing Tips - Polish Balling Up?

Paul D. Oakey in Lapidary Journal had trouble with his polish "balling up" and scratching the stone, and remedied the problem by using a solution of one ounce of vinegar to sixteen ounces of water.

He recommended cleaning the lap first with a toothbrush and the vinegar solution while the lap is turning at high speed. This procedure rejuvenated an old discarded Lucite lap. The solution should contain a little soap as a wetting agent. He dripped this slowly on the lap while polishing, thus ending his scratching problems.

Oakey said this gave good results with quartz, beryl, and YAG using either tin oxide, cerium oxide, or Linde A. To polish a large table, he mixed polish, vinegar, Karo syrup and soap into a creamy paste and applied it to the lap without a drip. –

From the Rocket City Rocks and Gems June/July 1999

via Strata Data 9/05.”

Using acid as an assist is polishing is an area that many faceters and cabochon cutters avoid, Too dangerous.

Yes, it can be dangerous. But please remember that plain vinegar contains enough acid to virtually eliminate scratching problems. You’ll be pleasantly gratified at the scratch-eliminating contributions of a bit of vinegar added to either chemical or diamond polish.

Via Rock Chips 7/03"

“Polishing Tips - Polish Balling Up?

Paul D. Oakey in Lapidary Journal had trouble with his polish "balling up" and scratching the stone, and remedied the problem by using a solution of one ounce of vinegar to sixteen ounces of water.

He recommended cleaning the lap first with a toothbrush and the vinegar solution while the lap is turning at high speed. This procedure rejuvenated an old discarded Lucite lap. The solution should contain a little soap as a wetting agent. He dripped this slowly on the lap while polishing, thus ending his scratching problems.

Oakey said this gave good results with quartz, beryl, and YAG using either tin oxide, cerium oxide, or Linde A. To polish a large table, he mixed polish, vinegar, Karo syrup and soap into a creamy paste and applied it to the lap without a drip. –

From the Rocket City Rocks and Gems June/July 1999

via Strata Data 9/05.”

B. Polishing Compounds.

There are many kinds of polishing powders and modifications of them for sale. The latter include bars, sticks, liquids, slurries and other mixtures, often sold under a trade name.

Nearly all polishing powders are mineral oxides, such as rouge (iron oxide), tin oxide, chrome oxide and many others. Occasionally two or more of these are mixed and sold under a trade name. They may be mixed with some cohesive substance and sold as a bar or stick; rouge is a good example. A few have been suspended in an emulsion and sold as slurry.

Black rouge is for gold, silver, and German Silver. It will give a very high polish. Do not press too hard, as it will heat and cause some of the colors on the wonder stones to actually run or blend together. This is true with most all of your polishes on this kind of material.

Green rouge is for polishing platinum, chrome, stainless steel, and hard materials. I have found that it will give a high polish to most of the jade materials that will stand a lot of heat. Try it on a piece of waste first, as it sometimes has a tendency to stain the cab. It is really on green jade or other green-like material.

Red rouge is for gold, silver, and soft metals and materials. It works well on soft buff wheels for a final finish, Try not to put it on too heavily, and you will get a better finish. Use a light touch, and I do not recommend the use of red rouge on soft materials, as it has a tendency to discolor the material, but it is fine for most of the metals.

White rouge is for the harder metals; platinum, chrome, stainless steel, or some of the harder material.

Then, there is the good old zam. It is mildly abrasive. Use with tight-weave muslin wheels for soft stones like turquoise and variscite. It is also good for a nice polish on silver, brass, copper, epoxies and plastics.

Hints: The initial surface should be prepared with a slightly rougher abrasive such as Tripoli.

Avoid surface drag lines on stone, epoxy or plastic by not letting the buff get too hot.

A list of polishing Compounds:

(Best Practice: dedicate a buff and lap pan to a particular polish and simply recharge with fresh polish as required to maintain effectiveness. Store in zip-lock bags to prevent contamination.)

CERIUM OXIDE - the best gemstone-polishing compound for most uses. It’s best with opal, agate, quartz, and obsidian. Not as effective with soft material or stones that tend to undercut.

MICRON ALUMINA - a 5-micron polishing powder developed for computer disks. It is the best polish for seashells, pretty good for soft stones and excellent as a pre-polish in vibratory tumblers and laps - not rotary tumblers.

ALUMINUM OXIDE, MAP - preferred by many to Linde A, this is a slightly faster and more economical rare earth polish that we call Miracle Atomic Polish.

TIN OXIDE - a long time favorite. Use on leather for polishing turquoise and all soft stones.

ZIRCONIUM OXIDE - a rare earth polish that is especially good for tumblers and laps. It’s the most economical effective polishing media. White and will not discolor gemstones.'

LINDE "A" - a tremendous favorite with gem cutters whether faceting or polishing cabs. Relatively expensive, you should consider polishing the stone then giving it a quick hit with Linde A to attain a super polish. It is available as powder to mix with water or an emulsified cream with the consistency of hand lotion that does not separate in solution.

OXALIC ACID - used for polishing carbonate type onyx when mixed with another polish such as Tin Oxide. In a strong solution with water, it is used to clean iron stains from specimens, ie. Quartz. Mix with hot tap water by stirring in oxalic crystals until the water is saturated and will not dissolve any more.

Crystals forming along the sides of the container indicate a saturated solution and should they disappear, you need to add more. WARNING: while this is a relatively mild acid all precautions must be taken to keep it out of eye, mouth, etc.

Editor’s note: Recent discussions on one of the internet rock lists centered around using diatomaceous earth (silica) such as is used in pool filters for a polishing compound.

I’ve tested it and while, by itself, I only came up with so-so results, adding a small amount of a regular polishing compound produced great results. It makes a great extender. I used about $1 of polish/diatomaceous earth in place of $3-4 of polish alone. 25 lbs was something like $10. About a pound of this along with an ounce or so of synthetic tin oxide produced a great

polish. That was in a 25 lb vibratory tumbler. The material has a very large volume per pound while dry so 25 lbs is a large box.

Also, the above list is far from complete but is a good starting point of fairly common polishes.

Via The Rockcollector 9/01

One can cut down on the variety needed by using one of the following on the right type of lap for a particular stone: cerium oxide, Linde A or B, chrome oxide, powdered red rouge and ZAM in stick form. The above will polish just about all stones that the amateur will encounter except the super hard ones such as corundum, chrysoberyl, cubic zirconium and a few others.

Yellow rouge is more of roughing in, as it cuts faster. It usually has a base of beeswax to hold the polish in. It is for hard materials such as chrome and stainless steel. It will produce a bright polish after you have used the polish wheel.

(Best Practice: dedicate a buff and lap pan to a particular polish and simply recharge with fresh polish as required to maintain effectiveness. Store in zip-lock bags to prevent contamination.)

CERIUM OXIDE - the best gemstone-polishing compound for most uses. It’s best with opal, agate, quartz, and obsidian. Not as effective with soft material or stones that tend to undercut.

MICRON ALUMINA - a 5-micron polishing powder developed for computer disks. It is the best polish for seashells, pretty good for soft stones and excellent as a pre-polish in vibratory tumblers and laps - not rotary tumblers.

ALUMINUM OXIDE, MAP - preferred by many to Linde A, this is a slightly faster and more economical rare earth polish that we call Miracle Atomic Polish.

TIN OXIDE - a long time favorite. Use on leather for polishing turquoise and all soft stones.

ZIRCONIUM OXIDE - a rare earth polish that is especially good for tumblers and laps. It’s the most economical effective polishing media. White and will not discolor gemstones.'

LINDE "A" - a tremendous favorite with gem cutters whether faceting or polishing cabs. Relatively expensive, you should consider polishing the stone then giving it a quick hit with Linde A to attain a super polish. It is available as powder to mix with water or an emulsified cream with the consistency of hand lotion that does not separate in solution.

OXALIC ACID - used for polishing carbonate type onyx when mixed with another polish such as Tin Oxide. In a strong solution with water, it is used to clean iron stains from specimens, ie. Quartz. Mix with hot tap water by stirring in oxalic crystals until the water is saturated and will not dissolve any more.

Crystals forming along the sides of the container indicate a saturated solution and should they disappear, you need to add more. WARNING: while this is a relatively mild acid all precautions must be taken to keep it out of eye, mouth, etc.

Editor’s note: Recent discussions on one of the internet rock lists centered around using diatomaceous earth (silica) such as is used in pool filters for a polishing compound.

I’ve tested it and while, by itself, I only came up with so-so results, adding a small amount of a regular polishing compound produced great results. It makes a great extender. I used about $1 of polish/diatomaceous earth in place of $3-4 of polish alone. 25 lbs was something like $10. About a pound of this along with an ounce or so of synthetic tin oxide produced a great

polish. That was in a 25 lb vibratory tumbler. The material has a very large volume per pound while dry so 25 lbs is a large box.

Also, the above list is far from complete but is a good starting point of fairly common polishes.

Via The Rockcollector 9/01

One can cut down on the variety needed by using one of the following on the right type of lap for a particular stone: cerium oxide, Linde A or B, chrome oxide, powdered red rouge and ZAM in stick form. The above will polish just about all stones that the amateur will encounter except the super hard ones such as corundum, chrysoberyl, cubic zirconium and a few others.

Yellow rouge is more of roughing in, as it cuts faster. It usually has a base of beeswax to hold the polish in. It is for hard materials such as chrome and stainless steel. It will produce a bright polish after you have used the polish wheel.

C. Applying the Polishing Compound.

You should have some good buffing wheels and there are quite a few of them: hickory, hard felt, chrome-tanned leather or muslin. Of course there are many other kinds of buffs, but those described here are easily obtained.

1. Hard felt wheels, for use with stones that will stand a lot of heat; they are usually made of wool.

2.Yellow muslin wheels, and it is tightly woven to help the coarser bobbing compound stay where it should be, so it will cut better. It is ventilated in the folds to help keep the material that you are working on cooler, so that it does not get too hot and chip.

3. Loose weave muslin buffs that throws threads all over, but does a really nice job for you. It will give you a beautiful finish, if you use red rouge or Zam on it.

4. Flannel buffs with no stitching that will give you a nice finish on the softer materials and it will work well with most of the polishes.

5 Heavy leather pad.

1. Hard felt wheels, for use with stones that will stand a lot of heat; they are usually made of wool.

2.Yellow muslin wheels, and it is tightly woven to help the coarser bobbing compound stay where it should be, so it will cut better. It is ventilated in the folds to help keep the material that you are working on cooler, so that it does not get too hot and chip.

3. Loose weave muslin buffs that throws threads all over, but does a really nice job for you. It will give you a beautiful finish, if you use red rouge or Zam on it.

4. Flannel buffs with no stitching that will give you a nice finish on the softer materials and it will work well with most of the polishes.

5 Heavy leather pad.

There are many kinds of polishes and different ways to do it, but here are some of the ways that have provided satisfactory results.

If you are using a polish that is mixed with water to a thick paste, as many of those powders are now available, try to keep your speed down to around 800 rpm. Then it will not have a tendency to throw your polish off This is why I like to use the bobbing compounds, as it is hard to get a motor that goes that slow. You can use these compounds that are listed above at most any speed, even as fast as 3000 rpm.

One more thing you should remember when you are polishing, is that you should hold your material at just a little below center, or right at the center, as your wheel will grab your piece and send it across the room. Be sure and wear safety glasses, as this rouge can fly off, and it is so fine that you might not notice it, but in a few days, when your eyes start to water, you will know it.

In most cases a buff should be rotated about 400 rpm. A little faster or slower is OK.

One exception is ZAM on muslin for turquoise. The buff can run at motor speed (1725 rpm) or faster. Variscite and malachite may also be polished with this method.

When using a powder, wet the buff down with a paintbrush or spray bottle before running the motor.

Paint the buff with the powder while still wet and then start the machine. The water will help carry away frictional heat, and the slower wheel will prevent build-up of heat and slow down the slinging off of the powder and water.

This system will prevent much loss of opals and other heat-sensitive stones. The slow wheel does not seem to slow the polishing action in most cases. There are exceptions, but there is no need to go into that in a short article.

For polishing jade, we find that heavy harness leather, at least an eighth inch thick is most suitable. Do not try to use light leather. A piece of felt floor covering makes a good cushion behind the leather. Chrome oxide is the most satisfactory polishing agent. Slow speed, not over 350 RPM for a ten-inch disc works best. Quite heavy pressure is generally required. Particularly for flat surfaces.

Add just enough water to keep the leather moist, applied with the chrome oxide in the form of a thin cream. Considerable pull will be felt as the leather dries cut. It is only while this pull or drag is felt, that actual polishing takes place.

Via The Laphound News Strata Data 9/05

Via The Rockcollector 11/05

One more thing you should remember when you are polishing, is that you should hold your material at just a little below center, or right at the center, as your wheel will grab your piece and send it across the room. Be sure and wear safety glasses, as this rouge can fly off, and it is so fine that you might not notice it, but in a few days, when your eyes start to water, you will know it.

In most cases a buff should be rotated about 400 rpm. A little faster or slower is OK.

One exception is ZAM on muslin for turquoise. The buff can run at motor speed (1725 rpm) or faster. Variscite and malachite may also be polished with this method.

When using a powder, wet the buff down with a paintbrush or spray bottle before running the motor.

Paint the buff with the powder while still wet and then start the machine. The water will help carry away frictional heat, and the slower wheel will prevent build-up of heat and slow down the slinging off of the powder and water.

This system will prevent much loss of opals and other heat-sensitive stones. The slow wheel does not seem to slow the polishing action in most cases. There are exceptions, but there is no need to go into that in a short article.

For polishing jade, we find that heavy harness leather, at least an eighth inch thick is most suitable. Do not try to use light leather. A piece of felt floor covering makes a good cushion behind the leather. Chrome oxide is the most satisfactory polishing agent. Slow speed, not over 350 RPM for a ten-inch disc works best. Quite heavy pressure is generally required. Particularly for flat surfaces.

Add just enough water to keep the leather moist, applied with the chrome oxide in the form of a thin cream. Considerable pull will be felt as the leather dries cut. It is only while this pull or drag is felt, that actual polishing takes place.

Via The Laphound News Strata Data 9/05

Via The Rockcollector 11/05

www.riogrande.com/Product/Zam-Cut-and-Polish-Compound/331123

Myers 0.3 micron Rapid Polish ( P.O. Box 646, Keller, Texas 76244 (817)379-5662) gets my vote as the best jade polish I have tried yet. I wrote an article in the June 1998 Rock and Gem magazine. (Rock and Gem can be reached at (805) 644-3824 if you are interested in back issues.) There is something about its structure that controls “orange peel”—the pitting resulting from some attempts to polish jade and other difficult stones—better than other polishes.

Myers 0.3 micron Rapid Polish ( P.O. Box 646, Keller, Texas 76244 (817)379-5662) gets my vote as the best jade polish I have tried yet. I wrote an article in the June 1998 Rock and Gem magazine. (Rock and Gem can be reached at (805) 644-3824 if you are interested in back issues.) There is something about its structure that controls “orange peel”—the pitting resulting from some attempts to polish jade and other difficult stones—better than other polishes.

Shop Hint

In shaping turquoise, it is advisable to use only the 220 wheel rather than the coarser ones. The 100 grit wheel will take desirable material from Such a soft stone.

Some of the more friable and chalky types of turquoise are difficult to polish with cerium or tin oxide; try a muslin buff with stick rouge. Since it is such a porous stone, oil may discolor it, so try sawing with a water coolant after soaking overnight in water. This helps prevent breaking.

Via Rock Chips 7/03

In shaping turquoise, it is advisable to use only the 220 wheel rather than the coarser ones. The 100 grit wheel will take desirable material from Such a soft stone.

Some of the more friable and chalky types of turquoise are difficult to polish with cerium or tin oxide; try a muslin buff with stick rouge. Since it is such a porous stone, oil may discolor it, so try sawing with a water coolant after soaking overnight in water. This helps prevent breaking.

Via Rock Chips 7/03

After you have polished your cab to what you believe is a good polish, try and buy a pre-polish and a good dry polish. Then put it in a vibrating tumbler and try running it for as long as the instructions call for. You will be surprised at the shine it has. Be sure and have enough dry polish in your tumbler to completely cover the cab or metal if it is a ring, or pendant without the chain, so that it does not have a chance to scratch the other ones. It is a lot quicker to use a small vibrator tumbler to do your final polish in.

To do this, pick it up with a clean white cloth or have a pair of white gloves on. There will not be any fingerprints on it if you do it correctly.

To do this, pick it up with a clean white cloth or have a pair of white gloves on. There will not be any fingerprints on it if you do it correctly.

OLD VERSION

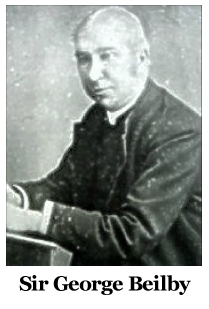

The Beilby Layer

What is the Beilby layer? It is a phenomenon that brings about a polished surface.

Sir George Beilby (17 November 1850 – 1 August 1924) discovered that during polishing the surface of gemstones actually melted and flowed as a “glassy” layer over very fine scratches. He proved it by noting a certain scratch pattern, polishing the surface, and then recovering the scratch pattern by etching away the polished surface with acids.

In 1937, a Mr. Finch, using another technique, confirmed this finding. He reported that there were two types of polish:

1. the Beilby flow and

2. the surface that has such fine scratches that it appeared polished.

The latter existed on those materials that were unable to flow in the Beilby manner.

The Beilby layer can occur in three ways.

First as an amorphous layer much like glass, e.g., the polish on zircon and spinel.

Secondly, as an amorphous layer, but parallel to crystal planes and crystallizing again in these lines, e.g., calcite.

In the third case, the layer forms by flowing but immediately crystallizes identically to the underlying material, e.g. quartz.

Distinguishing properties of the Beilby layer: It is very thin and usually slightly harder than the underlying material, probably due to packing of molecules by pressure.

There still remains some controversy over the existence of the Beilby Layer.

Some argue that the “flow” is not true melting, but rather a migration of molecules under pressure.

Polish seems to be the result of a combination of temperature, polishing agent, and pressure, and varies from material to material.

But does it really matter, as long as we get a good polish?

Author unknown, from Geolap News, Aug. 1997

Via Chippers Chatter 11/06

Via The RockCollector 11/06

What is the Beilby layer? It is a phenomenon that brings about a polished surface.

Sir George Beilby (17 November 1850 – 1 August 1924) discovered that during polishing the surface of gemstones actually melted and flowed as a “glassy” layer over very fine scratches. He proved it by noting a certain scratch pattern, polishing the surface, and then recovering the scratch pattern by etching away the polished surface with acids.

In 1937, a Mr. Finch, using another technique, confirmed this finding. He reported that there were two types of polish:

1. the Beilby flow and

2. the surface that has such fine scratches that it appeared polished.

The latter existed on those materials that were unable to flow in the Beilby manner.

The Beilby layer can occur in three ways.

First as an amorphous layer much like glass, e.g., the polish on zircon and spinel.

Secondly, as an amorphous layer, but parallel to crystal planes and crystallizing again in these lines, e.g., calcite.

In the third case, the layer forms by flowing but immediately crystallizes identically to the underlying material, e.g. quartz.

Distinguishing properties of the Beilby layer: It is very thin and usually slightly harder than the underlying material, probably due to packing of molecules by pressure.

There still remains some controversy over the existence of the Beilby Layer.

Some argue that the “flow” is not true melting, but rather a migration of molecules under pressure.

Polish seems to be the result of a combination of temperature, polishing agent, and pressure, and varies from material to material.

But does it really matter, as long as we get a good polish?

Author unknown, from Geolap News, Aug. 1997

Via Chippers Chatter 11/06

Via The RockCollector 11/06

Homers Corner

More on buffing and what to use to get a good polish.

You should have some good buffing wheels and there are quite a few of them.

There are hard felt wheels, for use with stones that will stand a lot of heat; they are usually made of wool. Then there is the yellow muslin wheel, and it is tightly woven to help the coarser bobbing compound stay where it should be, so it will cut better. It is ventilated in the folds to help keep the material that you are working on cooler, so that it does not get too hot and chip. There is the loose weave muslin buff that throws threads all over, but does a really nice job for you. It will give you a beautiful finish, if you use red rouge or Zam on it.

You will have a flannel buff with no stitching that will give you a nice finish on the softer materials and it will work well with most of the polishes.

These are some of the different kinds of polish compounds that are available to help get a good polish on your cab, or metal backing, as you are learning to make rings and other jewelry.

Yellow rouge is more of roughing in, as it cuts faster. It usually has a base of beeswax to hold the polish in. It is for hard materials such as chrome and stainless steel. It will produce a bright polish after you have used the polish wheel.

Black rouge is for gold, silver, and German Silver. It will give a very high polish. Do not press too hard, as it will heat and cause some of the colors on the wonder stones to actually run or blend together. This is true with most all of your polishes on this kind of material.

Green rouge is for polishing platinum, chrome, stainless steel, and hard materials. I have found that it will give a high polish to most of the jade materials that will stand a lot of heat. Try it on a piece of waste first, as it sometimes has a tendency to stain the cab. It is really on green jade or other green-like material.

Red rouge is for gold, silver, and soft metals and materials. It works well on soft buff wheels for a final finish, Try not to put it on too heavily, and you will get a better finish. Use a light touch, and I do not recommend the use of red rouge on soft materials, as it has a tendency to discolor the material, but it is fine for most of the metals.

White rouge is for the harder metals; platinum, chrome, stainless steel, or some of the harder material.

Then, there is the good old Zam. It is good for your softer material, like turquoise and variscite. It is also good for a nice polish on silver, brass, copper, etc.

There are many kinds of polishes and different ways to do it, but these are some of the ways that I have tried and had satisfactory results with.

If you are using a polish that is mixed with water to a thick paste, as many of those powders are now available, try to keep your speed down to around 800 rpm. Then it will not have a tendency to throw your polish off This is why I like to use the bobbing compounds, as it is hard to get a motor that goes that slow. You can use these compounds that are listed above at most any speed, even as fast as 3000 rpm.

One more thing you should remember when you are polishing, is that you should hold your material at just a little below center, or right at the center, as your wheel will grab your piece and send it across the room. Be sure and wear safety glasses, as this rouge can fly off, and it is so fine that you might not notice it, but in a few days, when your eyes start to water, you will know it.

After you have polished your cab to what you believe is a good polish, try and buy a pre-polish and a good dry polish. Then put it a tumbler and try running it for as long as the instructions call for. You will be surprised at the shine it has. Be sure and have enough dry polish in your tumbler to completely cover the cab or metal if it is a ring, or pendant without the chain, so that it does not have a chance to scratch the other ones. It is a lot quicker to use a small vibrator tumbler to do your final polish in.

To do this, pick it up with a clean white cloth or have a pair of white gloves on. There will not be any fingerprints on it if you do it correctly.

Homer C. Whitlock

Via News & Views 4/03

Note: Homer C. Whitlock from the Wasatch club passed away 17 Feb 2006 at the LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City. Our sympathies go out to his family.

More on buffing and what to use to get a good polish.

You should have some good buffing wheels and there are quite a few of them.

There are hard felt wheels, for use with stones that will stand a lot of heat; they are usually made of wool. Then there is the yellow muslin wheel, and it is tightly woven to help the coarser bobbing compound stay where it should be, so it will cut better. It is ventilated in the folds to help keep the material that you are working on cooler, so that it does not get too hot and chip. There is the loose weave muslin buff that throws threads all over, but does a really nice job for you. It will give you a beautiful finish, if you use red rouge or Zam on it.

You will have a flannel buff with no stitching that will give you a nice finish on the softer materials and it will work well with most of the polishes.

These are some of the different kinds of polish compounds that are available to help get a good polish on your cab, or metal backing, as you are learning to make rings and other jewelry.

Yellow rouge is more of roughing in, as it cuts faster. It usually has a base of beeswax to hold the polish in. It is for hard materials such as chrome and stainless steel. It will produce a bright polish after you have used the polish wheel.

Black rouge is for gold, silver, and German Silver. It will give a very high polish. Do not press too hard, as it will heat and cause some of the colors on the wonder stones to actually run or blend together. This is true with most all of your polishes on this kind of material.

Green rouge is for polishing platinum, chrome, stainless steel, and hard materials. I have found that it will give a high polish to most of the jade materials that will stand a lot of heat. Try it on a piece of waste first, as it sometimes has a tendency to stain the cab. It is really on green jade or other green-like material.

Red rouge is for gold, silver, and soft metals and materials. It works well on soft buff wheels for a final finish, Try not to put it on too heavily, and you will get a better finish. Use a light touch, and I do not recommend the use of red rouge on soft materials, as it has a tendency to discolor the material, but it is fine for most of the metals.

White rouge is for the harder metals; platinum, chrome, stainless steel, or some of the harder material.

Then, there is the good old Zam. It is good for your softer material, like turquoise and variscite. It is also good for a nice polish on silver, brass, copper, etc.

There are many kinds of polishes and different ways to do it, but these are some of the ways that I have tried and had satisfactory results with.

If you are using a polish that is mixed with water to a thick paste, as many of those powders are now available, try to keep your speed down to around 800 rpm. Then it will not have a tendency to throw your polish off This is why I like to use the bobbing compounds, as it is hard to get a motor that goes that slow. You can use these compounds that are listed above at most any speed, even as fast as 3000 rpm.

One more thing you should remember when you are polishing, is that you should hold your material at just a little below center, or right at the center, as your wheel will grab your piece and send it across the room. Be sure and wear safety glasses, as this rouge can fly off, and it is so fine that you might not notice it, but in a few days, when your eyes start to water, you will know it.

After you have polished your cab to what you believe is a good polish, try and buy a pre-polish and a good dry polish. Then put it a tumbler and try running it for as long as the instructions call for. You will be surprised at the shine it has. Be sure and have enough dry polish in your tumbler to completely cover the cab or metal if it is a ring, or pendant without the chain, so that it does not have a chance to scratch the other ones. It is a lot quicker to use a small vibrator tumbler to do your final polish in.

To do this, pick it up with a clean white cloth or have a pair of white gloves on. There will not be any fingerprints on it if you do it correctly.

Homer C. Whitlock

Via News & Views 4/03

Note: Homer C. Whitlock from the Wasatch club passed away 17 Feb 2006 at the LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City. Our sympathies go out to his family.

How to Use Polishing Powders

By Martin Koning, Lapidary Charm

There are many kinds of polishing powders and modifications of them for sale. The latter include bars, sticks, liquids, slurries and other mixtures, often sold under a trade name.

Nearly all polishing powders are mineral oxides, such as rouge (iron oxide), tin oxide, chrome oxide and many others. Occasionally two or more of these are mixed and sold under a trade name. They may be mixed with some cohesive substance and sold as a bar or stick; rouge is a good example. A few have been suspended in an emulsion and sold as slurry.

All forms will work on some stone; however, one can cut down the variety by using one of the following on the right type of lap for a particular stone: cerium oxide, Linde A or B, chrome oxide, powdered red rouge and ZAM in stick form. The above will polish just about all stones that the amateur will encounter except the super hard ones such as corundum, chrysoberyl, cubic zirconium and a few others.

The buffs one uses with these powders can be hickory, hard felt, chrome-tanned leather or muslin. Of course, these powders can be used on many other kinds of buffs, but the above-mentioned ones can be obtained easily. In most cases a buff should be rotated about 400 rpm. A little faster or slower is OK.

One exception is ZAM on muslin for turquoise. The buff can run at motor speed (1725 rpm) or faster. Variscite and malachite may also be polished with this method.

When using a powder, wet the buff down with a paintbrush or spray bottle before running the motor.

Paint the buff with the powder while still wet and then start the machine. The water will help carry away frictional heat, and the slower wheel will prevent build-up of heat and slow down the slinging off of the powder and water.

This system will prevent much loss of opals and other heat-sensitive stones. The slow wheel does not seem to slow the polishing action in most cases. There are exceptions, but there is no need to go into that in a short article.

From Rocky Mountain Federation, in The Rocky Mountain

News (RMF Newsletter), via GCL&FS Newsletter 10/00

By Martin Koning, Lapidary Charm

There are many kinds of polishing powders and modifications of them for sale. The latter include bars, sticks, liquids, slurries and other mixtures, often sold under a trade name.

Nearly all polishing powders are mineral oxides, such as rouge (iron oxide), tin oxide, chrome oxide and many others. Occasionally two or more of these are mixed and sold under a trade name. They may be mixed with some cohesive substance and sold as a bar or stick; rouge is a good example. A few have been suspended in an emulsion and sold as slurry.

All forms will work on some stone; however, one can cut down the variety by using one of the following on the right type of lap for a particular stone: cerium oxide, Linde A or B, chrome oxide, powdered red rouge and ZAM in stick form. The above will polish just about all stones that the amateur will encounter except the super hard ones such as corundum, chrysoberyl, cubic zirconium and a few others.

The buffs one uses with these powders can be hickory, hard felt, chrome-tanned leather or muslin. Of course, these powders can be used on many other kinds of buffs, but the above-mentioned ones can be obtained easily. In most cases a buff should be rotated about 400 rpm. A little faster or slower is OK.

One exception is ZAM on muslin for turquoise. The buff can run at motor speed (1725 rpm) or faster. Variscite and malachite may also be polished with this method.

When using a powder, wet the buff down with a paintbrush or spray bottle before running the motor.

Paint the buff with the powder while still wet and then start the machine. The water will help carry away frictional heat, and the slower wheel will prevent build-up of heat and slow down the slinging off of the powder and water.

This system will prevent much loss of opals and other heat-sensitive stones. The slow wheel does not seem to slow the polishing action in most cases. There are exceptions, but there is no need to go into that in a short article.

From Rocky Mountain Federation, in The Rocky Mountain

News (RMF Newsletter), via GCL&FS Newsletter 10/00

Lapidary Polishing Compounds

For economy, dedicate a buff and lap pan to a particular polish and simply recharge with fresh polish as required to maintain effectiveness.

CERIUM OXIDE - the best gemstone-polishing compound for most uses. It’s best with opal, agate, quartz, and obsidian. Not as effective with soft material or stones that tend to undercut.

MICRON ALUMINA - a 5-micron polishing powder developed for computer disks. It is the best polish for seashells, pretty good for soft stones and excellent as a pre-polish in vibratory tumblers and laps - not rotary tumblers.

ALUMINUM OXIDE, MAP - preferred by many to Linde A, this is a slightly faster and more economical rare earth polish that we call Miracle Atomic Polish.

TIN OXIDE - a long time favorite. Use on leather for polishing turquoise and all soft stones.

ZIRCONIUM OXIDE - a rare earth polish that is especially good for tumblers and laps. It’s the most economical effective polishing media. White and will not discolor gemstones.'

LINDE "A" - a tremendous favorite with gem cutters whether faceting or polishing cabs. Relatively expensive, you should consider polishing the stone then giving it a quick hit with Linde A to attain a super polish. It is available as powder to mix with water or an emulsified cream with the consistency of hand lotion that does not separate in solution.

OXALIC ACID - used for polishing carbonate type onyx when mixed with another polish such as Tin Oxide. In a strong solution with water, it is used to clean iron stains from specimens, ie. Quartz. Mix with hot tap water by stirring in oxalic crystals until the water is saturated and will not dissolve any more.

Crystals forming along the sides of the container indicate a saturated solution and should they disappear, you need to add more. WARNING: while this is a relatively mild acid all precautions must be taken to keep it out of eye, mouth, etc.

via Golden Spike News 4/01 via Owyhee Gem, 8/01

Editor’s note: Recent discussions on one of the internet rock lists centered around using diatomaceous earth (silica) such as is used in pool filters for a polishing compound.

I’ve tested it and while, by itself, I only came up with so-so results, adding a small amount of a regular polishing compound produced great results. It makes a great extender. I used about $1 of polish/diatomaceous earth in place of $3-4 of polish alone. 25 lbs was something like $10. About a pound of this along with an ounce or so of synthetic tin oxide produced a great

polish. That was in a 25 lb vibratory tumbler. The material has a very large volume per pound while dry so 25 lbs is a large box.

Also, the above list is far from complete but is a good starting point of fairly common polishes.

Via The Rockcollector 9/01

For economy, dedicate a buff and lap pan to a particular polish and simply recharge with fresh polish as required to maintain effectiveness.

CERIUM OXIDE - the best gemstone-polishing compound for most uses. It’s best with opal, agate, quartz, and obsidian. Not as effective with soft material or stones that tend to undercut.

MICRON ALUMINA - a 5-micron polishing powder developed for computer disks. It is the best polish for seashells, pretty good for soft stones and excellent as a pre-polish in vibratory tumblers and laps - not rotary tumblers.

ALUMINUM OXIDE, MAP - preferred by many to Linde A, this is a slightly faster and more economical rare earth polish that we call Miracle Atomic Polish.

TIN OXIDE - a long time favorite. Use on leather for polishing turquoise and all soft stones.

ZIRCONIUM OXIDE - a rare earth polish that is especially good for tumblers and laps. It’s the most economical effective polishing media. White and will not discolor gemstones.'

LINDE "A" - a tremendous favorite with gem cutters whether faceting or polishing cabs. Relatively expensive, you should consider polishing the stone then giving it a quick hit with Linde A to attain a super polish. It is available as powder to mix with water or an emulsified cream with the consistency of hand lotion that does not separate in solution.

OXALIC ACID - used for polishing carbonate type onyx when mixed with another polish such as Tin Oxide. In a strong solution with water, it is used to clean iron stains from specimens, ie. Quartz. Mix with hot tap water by stirring in oxalic crystals until the water is saturated and will not dissolve any more.

Crystals forming along the sides of the container indicate a saturated solution and should they disappear, you need to add more. WARNING: while this is a relatively mild acid all precautions must be taken to keep it out of eye, mouth, etc.

via Golden Spike News 4/01 via Owyhee Gem, 8/01

Editor’s note: Recent discussions on one of the internet rock lists centered around using diatomaceous earth (silica) such as is used in pool filters for a polishing compound.

I’ve tested it and while, by itself, I only came up with so-so results, adding a small amount of a regular polishing compound produced great results. It makes a great extender. I used about $1 of polish/diatomaceous earth in place of $3-4 of polish alone. 25 lbs was something like $10. About a pound of this along with an ounce or so of synthetic tin oxide produced a great

polish. That was in a 25 lb vibratory tumbler. The material has a very large volume per pound while dry so 25 lbs is a large box.

Also, the above list is far from complete but is a good starting point of fairly common polishes.

Via The Rockcollector 9/01

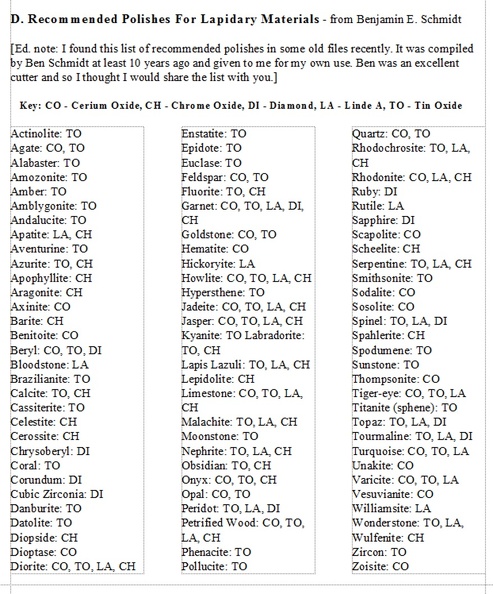

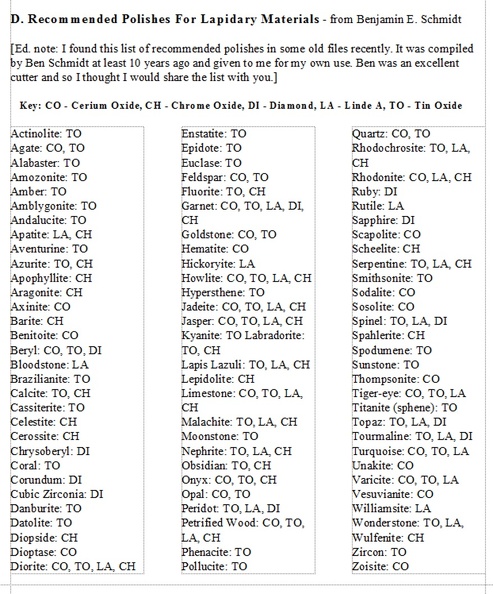

Recommended Polishes For Lapidary Materials - from Benjamin E. Schmidt

[Ed. note: I found this list of recommended polishes in some old files recently. It was compiled by Ben Schmidt at least 10 years ago and given to me for my own use. Ben was an excellent cutter and so I thought I would share the list with you.]

Key: CO - Cerium Oxide, CH - Chrome Oxide, DI - Diamond, LA - Linde A, TO - Tin Oxide

Actinolite: TO

Agate: CO, TO

Alabaster: TO

Amozonite: TO

Amber: TO

Amblygonite: TO

Andalucite: TO

Apatite: LA, CH

Aventurine: TO

Azurite: TO, CH

Apophyllite: CH

Aragonite: CH

Axinite: CO

Barite: CH

Benitoite: CO

Beryl: CO, TO, DI

Bloodstone: LA

Brazilianite: TO

Calcite: TO, CH

Cassiterite: TO

Celestite: CH

Cerossite: CH

Chrysoberyl: DI

Coral: TO

Corundum: DI

Cubic Zirconia: DI

Danburite: TO

Datolite: TO

Diopside: CH

Dioptase: CO

Diorite: CO, TO, LA, CH

Enstatite: TO

Epidote: TO

Euclase: TO

Feldspar: CO, TO

Fluorite: TO, CH

Garnet: CO, TO, LA, DI, CH

Goldstone: CO, TO

Hematite: CO

Hickoryite: LA

Howlite: CO, TO, LA, CH

Hypersthene: TO

Jadeite: CO, TO, LA, CH

Jasper: CO, TO, LA, CH

Kyanite: TO Labradorite: TO, CH

Lapis Lazuli: TO, LA, CH

Lepidolite: CH

Limestone: CO, TO, LA, CH

Malachite: TO, LA, CH

Moonstone: TO

Nephrite: TO, LA, CH

Obsidian: TO, CH

Onyx: CO, TO, CH

Opal: CO, TO

Peridot: TO, LA, DI

Petrified Wood: CO, TO, LA, CH

Phenacite: TO

Pollucite: TO

Quartz: CO, TO

Rhodochrosite: TO, LA, CH

Rhodonite: CO, LA, CH

Ruby: DI

Rutile: LA

Sapphire: DI

Scapolite: CO

Scheelite: CH

Serpentine: TO, LA, CH

Smithsonite: TO

Sodalite: CO

Sosolite: CO

Spinel: TO, LA, DI

Spahlerite: CH

Spodumene: TO

Sunstone: TO

Thompsonite: CO

Tiger-eye: CO, TO, LA

Titanite (sphene): TO

Topaz: TO, LA, DI

Tourmaline: TO, LA, DI

Turquoise: CO, TO, LA

Unakite: CO

Varicite: CO, TO, LA

Vesuvianite: CO

Williamsite: LA

Wonderstone: TO, LA,

Wulfenite: CH

Zircon: TO

Zoisite: CO

GEM CUTTERS NEWS 3/98

via Glacial Drifter 12/99

Polishing Tips

Polish Balling Up?

Paul D. Oakey in Lapidary Journal had trouble with his polish "balling up" and scratching the stone, and remedied the problem by using a solution of one ounce of vinegar to sixteen ounces of water.

He recommended cleaning the lap first with a toothbrush and the vinegar solution while the lap is turning at high speed. This procedure rejuvenated an old discarded Lucite lap. The solution should contain a little soap as a wetting agent. He dripped this slowly on the lap while polishing, thus ending his scratching problems.

Oakey said this gave good results with quartz, beryl, and YAG using either tin oxide, cerium oxide, or Linde A. To polish a large table, he mixed polish, vinegar, Karo syrup and soap into a creamy paste and applied it to the lap without a drip. –

From the Rocket City Rocks and Gems June/July 1999

via Strata Data 9/05.

For polishing jade, we find that heavy harness leather, at least an eighth inch thick is most suitable. Do not try to use light leather. A piece of felt floor covering makes a good cushion behind the leather. Chrome oxide is the most satisfactory polishing agent. Slow speed, not over 350 RPM for a ten-inch disc works best. Quite heavy pressure is generally required. Particularly for flat surfaces.

Add just enough water to keep the leather moist, applied with the chrome oxide in the form of a thin cream. Considerable pull will be felt as the leather dries cut. It is only while this pull or drag is felt, that actual polishing takes place.

Via The Laphound News Strata Data 9/05

Via The Rockcollector 11/05

Shop Hint

In shaping turquoise, it is advisable to use only the 220 wheel rather than the coarser ones. The 100 grit wheel will take desirable material from Such a soft stone.

Some of the more friable and chalky types of turquoise are difficult to polish with cerium or tin oxide; try a muslin buff with stick rouge. Since it is such a porous stone, oil may discolor it, so try sawing with a water coolant after soaking overnight in water. This helps prevent breaking.

Via Rock Chips 7/03

Can Vinegar Help Polishing?

Using acid as an assist in polishing is an area that many faceters and cabochon cutters avoid, Too dangerous.

Yes, it can be dangerous. But please remember that plain vinegar contains enough acid to virtually eliminate scratching problems. You’ll be pleasantly gratified at the scratch-eliminating contributions of a bit of vinegar added to either chemical or diamond polish.

Via Rock Chips 7/03

[Ed. note: I found this list of recommended polishes in some old files recently. It was compiled by Ben Schmidt at least 10 years ago and given to me for my own use. Ben was an excellent cutter and so I thought I would share the list with you.]

Key: CO - Cerium Oxide, CH - Chrome Oxide, DI - Diamond, LA - Linde A, TO - Tin Oxide

Actinolite: TO

Agate: CO, TO

Alabaster: TO

Amozonite: TO

Amber: TO

Amblygonite: TO

Andalucite: TO

Apatite: LA, CH

Aventurine: TO

Azurite: TO, CH

Apophyllite: CH

Aragonite: CH

Axinite: CO

Barite: CH

Benitoite: CO

Beryl: CO, TO, DI

Bloodstone: LA

Brazilianite: TO

Calcite: TO, CH

Cassiterite: TO

Celestite: CH

Cerossite: CH

Chrysoberyl: DI

Coral: TO

Corundum: DI

Cubic Zirconia: DI

Danburite: TO

Datolite: TO

Diopside: CH

Dioptase: CO

Diorite: CO, TO, LA, CH

Enstatite: TO

Epidote: TO

Euclase: TO

Feldspar: CO, TO

Fluorite: TO, CH

Garnet: CO, TO, LA, DI, CH

Goldstone: CO, TO

Hematite: CO

Hickoryite: LA

Howlite: CO, TO, LA, CH

Hypersthene: TO

Jadeite: CO, TO, LA, CH

Jasper: CO, TO, LA, CH

Kyanite: TO Labradorite: TO, CH

Lapis Lazuli: TO, LA, CH

Lepidolite: CH

Limestone: CO, TO, LA, CH

Malachite: TO, LA, CH

Moonstone: TO

Nephrite: TO, LA, CH

Obsidian: TO, CH

Onyx: CO, TO, CH

Opal: CO, TO

Peridot: TO, LA, DI

Petrified Wood: CO, TO, LA, CH

Phenacite: TO

Pollucite: TO

Quartz: CO, TO

Rhodochrosite: TO, LA, CH

Rhodonite: CO, LA, CH

Ruby: DI

Rutile: LA

Sapphire: DI

Scapolite: CO

Scheelite: CH

Serpentine: TO, LA, CH

Smithsonite: TO

Sodalite: CO

Sosolite: CO

Spinel: TO, LA, DI

Spahlerite: CH

Spodumene: TO

Sunstone: TO

Thompsonite: CO

Tiger-eye: CO, TO, LA

Titanite (sphene): TO

Topaz: TO, LA, DI

Tourmaline: TO, LA, DI

Turquoise: CO, TO, LA

Unakite: CO

Varicite: CO, TO, LA

Vesuvianite: CO

Williamsite: LA

Wonderstone: TO, LA,

Wulfenite: CH

Zircon: TO

Zoisite: CO

GEM CUTTERS NEWS 3/98

via Glacial Drifter 12/99

Polishing Tips

Polish Balling Up?

Paul D. Oakey in Lapidary Journal had trouble with his polish "balling up" and scratching the stone, and remedied the problem by using a solution of one ounce of vinegar to sixteen ounces of water.

He recommended cleaning the lap first with a toothbrush and the vinegar solution while the lap is turning at high speed. This procedure rejuvenated an old discarded Lucite lap. The solution should contain a little soap as a wetting agent. He dripped this slowly on the lap while polishing, thus ending his scratching problems.

Oakey said this gave good results with quartz, beryl, and YAG using either tin oxide, cerium oxide, or Linde A. To polish a large table, he mixed polish, vinegar, Karo syrup and soap into a creamy paste and applied it to the lap without a drip. –

From the Rocket City Rocks and Gems June/July 1999

via Strata Data 9/05.

For polishing jade, we find that heavy harness leather, at least an eighth inch thick is most suitable. Do not try to use light leather. A piece of felt floor covering makes a good cushion behind the leather. Chrome oxide is the most satisfactory polishing agent. Slow speed, not over 350 RPM for a ten-inch disc works best. Quite heavy pressure is generally required. Particularly for flat surfaces.

Add just enough water to keep the leather moist, applied with the chrome oxide in the form of a thin cream. Considerable pull will be felt as the leather dries cut. It is only while this pull or drag is felt, that actual polishing takes place.

Via The Laphound News Strata Data 9/05

Via The Rockcollector 11/05

Shop Hint

In shaping turquoise, it is advisable to use only the 220 wheel rather than the coarser ones. The 100 grit wheel will take desirable material from Such a soft stone.

Some of the more friable and chalky types of turquoise are difficult to polish with cerium or tin oxide; try a muslin buff with stick rouge. Since it is such a porous stone, oil may discolor it, so try sawing with a water coolant after soaking overnight in water. This helps prevent breaking.

Via Rock Chips 7/03

Can Vinegar Help Polishing?

Using acid as an assist in polishing is an area that many faceters and cabochon cutters avoid, Too dangerous.

Yes, it can be dangerous. But please remember that plain vinegar contains enough acid to virtually eliminate scratching problems. You’ll be pleasantly gratified at the scratch-eliminating contributions of a bit of vinegar added to either chemical or diamond polish.

Via Rock Chips 7/03