Post by 1dave on Apr 12, 2017 9:03:27 GMT -5

When a Giant Asteroid Impact Created it's own Magma.

You will have to go to the above site to read the whole article.

Landsat 8 image of the Sudbury Basin in Ontario, taken in September 2013. USGS/NASA

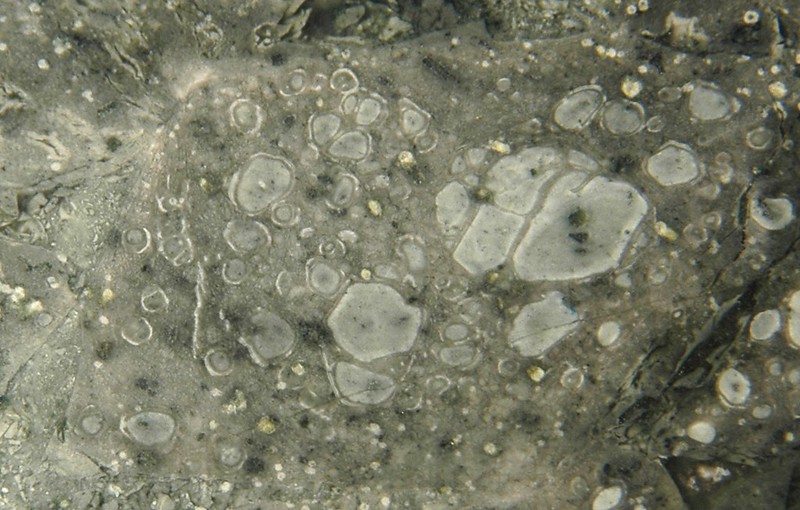

The impact breccia (“astroclastic”) material from the Sudbury impact, with chunks of crust, pieces of impact melt and ash. The deposit itself looks remarkably like a volcanic pyroclastic flow deposit. The piece is roughly 30 cm across. Click to see a larger version. Erik Klemetti

You will have to go to the above site to read the whole article.

Landsat 8 image of the Sudbury Basin in Ontario, taken in September 2013. USGS/NASA

One of the best examples on Earth for this kind of cataclysmic volcanism in found in Canada. The Sudbury Basin in Ontario (see above) contains the remnants of a massive asteroid impact that occurred ~1.8 billion years ago. Today, the remains of the crater are perched up against some of the oldest rocks on Earth, namely the Canadian Shield, where the rocks are 2-2.6 billion years old. It is into these ancient rocks that the Sudbury asteroid slammed, creating what is thought to be a crater at least 200 kilometers across. All that remains today is an elliptical sequence of rocks ~50 kilometers across as most of the impact features have been long since eroded. However, this scar on the Earth’s surface might also be one of its most valuable, with over $500 billion worth of nickel, copper, platinum-group and other rare metals in its deposits.

We do find small blebs of melt in the deposits from other impacts, but by volume, they are an insignificant part of the impact. However, at Sudbury, it seems that the force of the eruption was enough to create hundreds of cubic kilometers (if not more) of magma. Most of this magma stayed in the ground and formed what we call a large igneous intrusion. These features, like the Stillwater Complex in Montana, are one of the few times we see direct evidence of that “magma chamber” that is (incorrectly) envisioned beneath a volcano. The magma body caused by the Sudbury impact was large enough to stay hot for sufficient time to allow minerals to crystallize and separate (fractionate) in the chamber.

Now, as I said, much of the evidence of the impact volcanism has been erased by erosion. However, there are some very strange rocks that could be best described as “astroclastic”. What do I mean by that? Remember, “pyroclastic” rocks are generated from a fluidized flow of how volcanic debris and rocks during an explosive eruption. In the Sudbury area, we find “impact breccia” (a term for broken debris with a finer material) that consists of blocks of crust, blobs of impact melt and even accretionary lapilli (raindrops coated with ash) that formed as the initial explosion caused by the impact fell back into the crater. The composition of the “astroclastic” material (see below) really does sound like a true hybrid between impact fallout and volcanic eruptions.

The impact breccia (“astroclastic”) material from the Sudbury impact, with chunks of crust, pieces of impact melt and ash. The deposit itself looks remarkably like a volcanic pyroclastic flow deposit. The piece is roughly 30 cm across. Click to see a larger version. Erik Klemetti