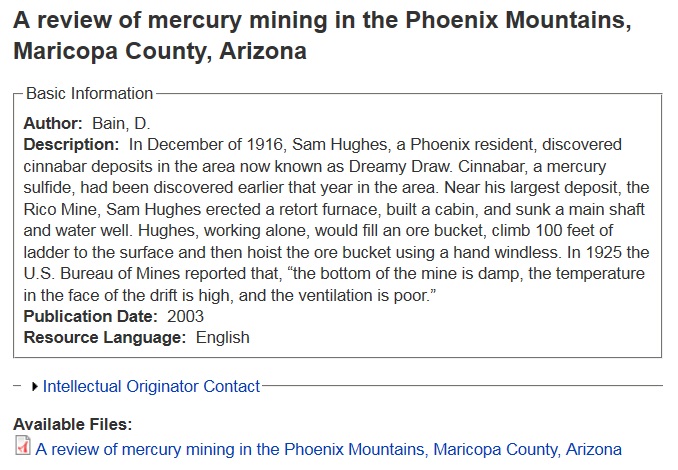

Post by 1dave on Dec 23, 2017 16:13:12 GMT -5

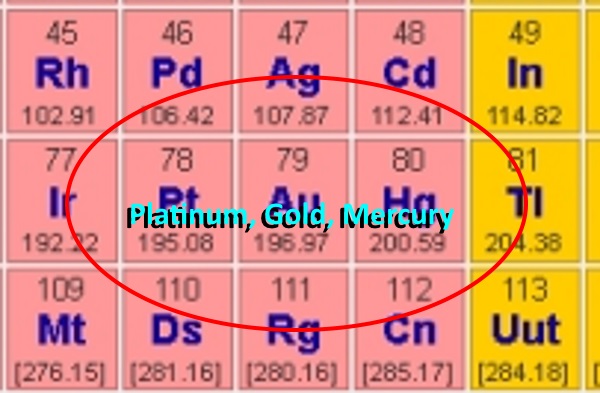

Platinum, gold, then Mercury. Good Company!

Around two thousand years ago, approximately 300 km south of Madrid in the Sierra Morena, Cinnabar was discovered.

The area was named Almadén from the Arabic word المعدن al-maʻdin, meaning 'The Mine'.

Originally a Roman (then Moorish) settlement, the town was captured in 1151 by Alfonso VII and given to the Knights of the Order of Calatrava.

The geology of the area is characterized by volcanism. Almadén is home to the world's greatest reserves of cinnabar, a mineral associated with recent volcanic activity, from which mercury is extracted.

It doesn't look like much today, but the mercury deposits of Almadén account for the largest quantity of liquid mercury metal produced in the world. Approximately 250,000 metric tons of mercury have been produced there in the past 2,000 years.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Almad%C3%A9n

The Fuggers of Augsburg, two German bankers, administered the mines during the 16th and 17th centuries in return for loans to the Spanish government. Mercury became very valuable in the Americas in the mid 16th century due to the introduction of amalgamation, a process that uses mercury to extract the metals from gold and silver ore. The demand for mercury grew, and so did the town's importance as a center of mining and industry. Most of the mercury produced at this time was sent to Seville, then to the Americas.

The dangerous working conditions of the mines made it difficult for the Fuggers to find willing laborers. As the demand for mercury grew, the idea of convict labor was introduced.

Introduction of convict labor in mine

After the Fuggers failed to meet production quotas in 1566, the King of Spain agreed to send 30 prisoners to serve their sentences as laborers at Almadén. The number was increased to 40 in 1583. The prisoners, known as forzados, were selected out of criminals waiting for transport to the galleys in the jail of Toledo. Those selected usually had limited sentences and good physical abilities. Murderers and capital criminals were rarely selected, as the galleys were considered a far harsher punishment than the mines of Almadén.

The first group of forzados arrived at Almadén at the end of February 1566.

Daily life at Almadén

A steady run of complaints to the king in the 1580s led to an investigation of convict living conditions at Almadén in 1593. The investigation was conducted by royal commissioner and famous author Mateo Alemán, and was based largely on convict interviews.

The mine at Almadén provided forzados with acceptable living conditions. Each convict received daily rations of meat, bread, and wine. Each year, a forzado was issued a doublet, one pair of breeches, stockings, two shirts, one pair of shoes, and a hood. Medical care was available at the infirmary, and the mine even housed its own apothecary.

Despite these good offerings, the danger of death or sickness from mercury poisoning was always present. 24% of convicts at Almadén between 1566 and 1593 died before their release dates, most often because of mercury poisoning. Nearly all prisoners experienced discomfort due to mercury exposure. Common symptoms included severe pains in any part of the body, trembling limbs, and loss of sanity. Most of the men at the furnaces died from poisoning.

Forzados were also forced to bail water out of the mines. These men escaped the dangers of mercury exposure, but suffered exhaustion on a daily basis. A group of four men had to bail out 300 buckets of water without rest. Those that could not meet this quota were whipped. Sick prisoners were not exempt from this practice.

Death was common, and the convicts wished to provide a proper burial for each of the men that died at the mine. A religious confraternity was formed, conducted by a prior who was administrator of the mine for the Fuggers. The prior also chose devout convicts to serve as officials. Mass was held on Sundays and feast days, and non-attendance was punishable by fine.

Slave labor

North African slaves were purchased directly from slaveholders to work alongside the convicts. These slaves were often much cheaper than others on the market at the time, and by 1613, slaves outnumbered forzados by a two-to-one ratio.

1645 to present

Cinnabar from Almaden, Hand-colored copper-plate engraving by James Sowerby, 1811

Cinnabar from Almaden

In 1645, the Fugger concession was cancelled and the mines were taken over by the state, to be managed by the royal government. All capital criminals were to be sent to Almadén by court order in 1749, but the mine simply could not accommodate all of them. The act was cancelled in 1751.

Two disastrous fires occurred in 1775 that were blamed on the forzados.

Safer mining technology was introduced in the last quarter of the 18th century, and free laborers began to take interest in the mine again. By the end of the century, free workers had replaced most of the slave labor. The penal establishment at Almadén was closed in 1801.

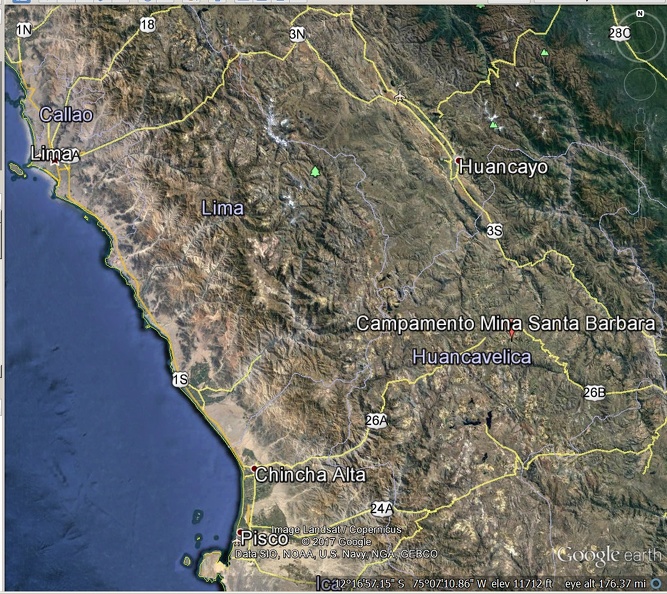

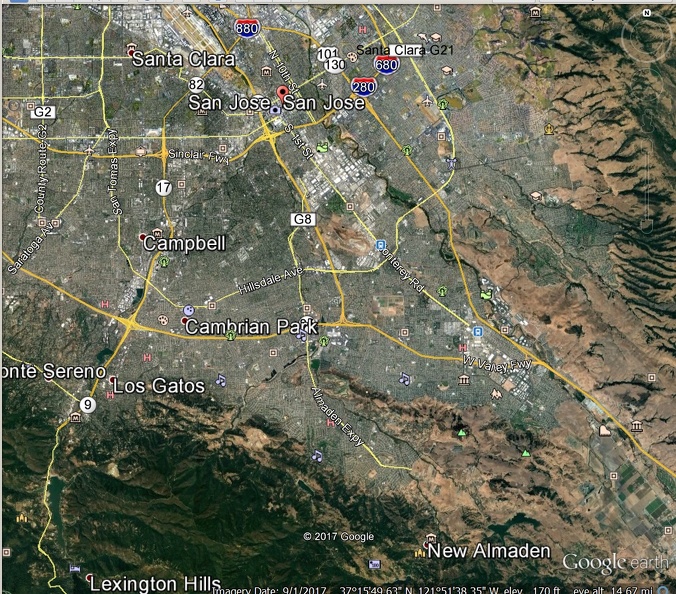

In 1835, during the First Carlist War, the mine was leased indefinitely to the Rothschild Bank. The price paid was high, but one of the Rothschild family firms had previously purchased the quicksilver mine in Idrija (now in Slovenia) from Austria; thus the firm had a monopoly on quicksilver (until discovery of New Almaden in California). Volume was expanded and the metal sold at a substantial markup returning a substantial profit to both Spain and the firm. Spain reclaimed the mine in 1863.[1]

In 1916, a special council was created to operate the mines, introducing new technology and safety improvements. A record production of 82,000 mercury flasks was reached in 1941, just after the Spanish Civil War. The price for mercury decreased from a peak of US$571 in 1965 to US$121 in 1976 making economic planning difficult. In 1981, the Spanish government created the company Minas de Almadén y Arrayanes to operate the mine. In 2000, the mines closed due to the fall of the price of mercury in the international market, caused by falling demand. However, Almadén still has one of the world's largest mercury resources.

Alamden is now a World Heritage Site, Heritage of Mercury. Almadén and Idrija. A museum has been built, including visit to the mines (areas from 16th to 20th century).

The Fuggers of Augsburg, two German bankers, administered the mines during the 16th and 17th centuries in return for loans to the Spanish government. Mercury became very valuable in the Americas in the mid 16th century due to the introduction of amalgamation, a process that uses mercury to extract the metals from gold and silver ore. The demand for mercury grew, and so did the town's importance as a center of mining and industry. Most of the mercury produced at this time was sent to Seville, then to the Americas.

The dangerous working conditions of the mines made it difficult for the Fuggers to find willing laborers. As the demand for mercury grew, the idea of convict labor was introduced.

Introduction of convict labor in mine

After the Fuggers failed to meet production quotas in 1566, the King of Spain agreed to send 30 prisoners to serve their sentences as laborers at Almadén. The number was increased to 40 in 1583. The prisoners, known as forzados, were selected out of criminals waiting for transport to the galleys in the jail of Toledo. Those selected usually had limited sentences and good physical abilities. Murderers and capital criminals were rarely selected, as the galleys were considered a far harsher punishment than the mines of Almadén.

The first group of forzados arrived at Almadén at the end of February 1566.

Daily life at Almadén

A steady run of complaints to the king in the 1580s led to an investigation of convict living conditions at Almadén in 1593. The investigation was conducted by royal commissioner and famous author Mateo Alemán, and was based largely on convict interviews.

The mine at Almadén provided forzados with acceptable living conditions. Each convict received daily rations of meat, bread, and wine. Each year, a forzado was issued a doublet, one pair of breeches, stockings, two shirts, one pair of shoes, and a hood. Medical care was available at the infirmary, and the mine even housed its own apothecary.

Despite these good offerings, the danger of death or sickness from mercury poisoning was always present. 24% of convicts at Almadén between 1566 and 1593 died before their release dates, most often because of mercury poisoning. Nearly all prisoners experienced discomfort due to mercury exposure. Common symptoms included severe pains in any part of the body, trembling limbs, and loss of sanity. Most of the men at the furnaces died from poisoning.

Forzados were also forced to bail water out of the mines. These men escaped the dangers of mercury exposure, but suffered exhaustion on a daily basis. A group of four men had to bail out 300 buckets of water without rest. Those that could not meet this quota were whipped. Sick prisoners were not exempt from this practice.

Death was common, and the convicts wished to provide a proper burial for each of the men that died at the mine. A religious confraternity was formed, conducted by a prior who was administrator of the mine for the Fuggers. The prior also chose devout convicts to serve as officials. Mass was held on Sundays and feast days, and non-attendance was punishable by fine.

Slave labor

North African slaves were purchased directly from slaveholders to work alongside the convicts. These slaves were often much cheaper than others on the market at the time, and by 1613, slaves outnumbered forzados by a two-to-one ratio.

1645 to present

Cinnabar from Almaden, Hand-colored copper-plate engraving by James Sowerby, 1811

Cinnabar from Almaden

In 1645, the Fugger concession was cancelled and the mines were taken over by the state, to be managed by the royal government. All capital criminals were to be sent to Almadén by court order in 1749, but the mine simply could not accommodate all of them. The act was cancelled in 1751.

Two disastrous fires occurred in 1775 that were blamed on the forzados.

Safer mining technology was introduced in the last quarter of the 18th century, and free laborers began to take interest in the mine again. By the end of the century, free workers had replaced most of the slave labor. The penal establishment at Almadén was closed in 1801.

In 1835, during the First Carlist War, the mine was leased indefinitely to the Rothschild Bank. The price paid was high, but one of the Rothschild family firms had previously purchased the quicksilver mine in Idrija (now in Slovenia) from Austria; thus the firm had a monopoly on quicksilver (until discovery of New Almaden in California). Volume was expanded and the metal sold at a substantial markup returning a substantial profit to both Spain and the firm. Spain reclaimed the mine in 1863.[1]

In 1916, a special council was created to operate the mines, introducing new technology and safety improvements. A record production of 82,000 mercury flasks was reached in 1941, just after the Spanish Civil War. The price for mercury decreased from a peak of US$571 in 1965 to US$121 in 1976 making economic planning difficult. In 1981, the Spanish government created the company Minas de Almadén y Arrayanes to operate the mine. In 2000, the mines closed due to the fall of the price of mercury in the international market, caused by falling demand. However, Almadén still has one of the world's largest mercury resources.

Alamden is now a World Heritage Site, Heritage of Mercury. Almadén and Idrija. A museum has been built, including visit to the mines (areas from 16th to 20th century).

Arrastras were used to crush the ore,

Arrastra

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Typical arrastra construction. From Mining and Scientific Press 52 (1886): 237.

Arrastra demonstration in Liberty, Washington, 2007.

An Arrastra (or Arastra) is a primitive mill for grinding and pulverizing (typically) gold or silver ore. The simplest form of the arrastra is two or more flat-bottomed drag stones placed in a circular pit paved with flat stones, and connected to a center post by a long arm. With a horse, mule or human providing power at the other end of the arm, the stones were dragged slowly around in a circle, crushing the ore.[1][2] Some arrastras were powered by a water wheel; a few were powered by steam or gasoline engines, and even electricity.[1]

Arrastras were widely used throughout the Mediterranean region since Phoenician times.[1] The Spanish introduced the arrastra to the New World in the 16th century. The word "arrastra" comes from the Spanish language arrastre, meaning to drag along the ground.[2] Arrastras were suitable for use in small or remote mines, since they could be built from local materials and required little investment capital.[2][3]

For gold ore, the gold was typically recovered by amalgamation with quicksilver. The miner would add clean mercury to the ground ore, continue grinding, rinse out the fines, then add more ore and repeat the process. At cleanup, the gold amalgam was carefully recovered from the low places and crevices in the arrastra floor. The amalgam was then heated in a distillation retort to recover the gold, and the mercury was saved for reuse.[3]

For silver ore, the patio process, invented in Mexico in 1554, was generally used to recover the silver from ore ground in the arrastra.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Typical arrastra construction. From Mining and Scientific Press 52 (1886): 237.

Arrastra demonstration in Liberty, Washington, 2007.

An Arrastra (or Arastra) is a primitive mill for grinding and pulverizing (typically) gold or silver ore. The simplest form of the arrastra is two or more flat-bottomed drag stones placed in a circular pit paved with flat stones, and connected to a center post by a long arm. With a horse, mule or human providing power at the other end of the arm, the stones were dragged slowly around in a circle, crushing the ore.[1][2] Some arrastras were powered by a water wheel; a few were powered by steam or gasoline engines, and even electricity.[1]

Arrastras were widely used throughout the Mediterranean region since Phoenician times.[1] The Spanish introduced the arrastra to the New World in the 16th century. The word "arrastra" comes from the Spanish language arrastre, meaning to drag along the ground.[2] Arrastras were suitable for use in small or remote mines, since they could be built from local materials and required little investment capital.[2][3]

For gold ore, the gold was typically recovered by amalgamation with quicksilver. The miner would add clean mercury to the ground ore, continue grinding, rinse out the fines, then add more ore and repeat the process. At cleanup, the gold amalgam was carefully recovered from the low places and crevices in the arrastra floor. The amalgam was then heated in a distillation retort to recover the gold, and the mercury was saved for reuse.[3]

For silver ore, the patio process, invented in Mexico in 1554, was generally used to recover the silver from ore ground in the arrastra.

www.reporterherald.com/ci_21960868/arrastra-remains-near-buena-vista

Jessen stands by an arrastra located north of Buena Vista in Chaffee County. A county road takes visitors with 400 feet of this rare, early mill used to grind gold ore. (Kenneth Jessen)

Arrastra remains near Buena Vista

By Kenneth Jessen

Posted: 11/11/2012 01:00:00 AM MST

An arrastra, in its simplest terms is a grinder and dates back to the fifth century B.C.

The grinding surface is typically flat bedrock situated near a stream. A vertical pocket is drilled into the rock and a pole is placed in the pocket. Attached to the pole near its base is an arm and attached to the arm, usually by chains, are heavy drag stones. Farther up the pole is a long horizontal beam that is used to turn the center pole.

As the pole is rotated, the heavy drag stone do the grinding against the bedrock surface. Small arrastras could be human powered and draft animals were used to turn larger examples.

The most common use in Colorado was to grind ore containing gold flakes. The ore was placed on the grinding surface and after hours the ore is pulverized into a fine powder. A small amount of mercury is added during the process to amalgamate the gold.

The gold-mercury amalgam settles to the bedrock while the worthless rock is washed away using water from the nearby stream. The amalgam is then collected and strained through a cloth to remove most of the mercury leaving behind a gold button. The remaining mercury is driven off in a retort, condensed and reused. The gold requires further refining to remove the remaining impurities.

Arrastras were used in the absence of large, efficient gold mills or in remote locations. They are very limited in the amount of material that could be processed.

Arrastras in Colorado are rare. Many have been cut out of the bedrock and moved to museums. One example, still in its original location and relatively easy to reach, is north of Buena Vista on Fourmile Creek. It requires only a short walk from a four-wheel drive road.

To reach this arrastra, follow Colorado Avenue north from downtown Buena Vista. The road crosses the Arkansas River and becomes County Road 371. Within sight of the first Colorado Midland Railroad tunnel, County Road 375 heads east and uphill. After a mile, take County Road 376 to the right to Fourmile Creek.

This road has many washouts and it quite sandy -- it may require four-wheel drive. After crossing the creek, there is a small parking area on the right. By stepping over a wire fence (not posted) and walking west, there is a wide gravel wash. By following the wash down hill, the arrastra is at the edge of the trees at a distance of about 400 feet.

Kenneth Jessen has been a Loveland resident since 1965. He is an author of 18 books and more than 1,300 articles. He was an engineer for Hewlett-Packard for 33 years and now works as a full-time author, lecturer and guide.

By Kenneth Jessen

Posted: 11/11/2012 01:00:00 AM MST

An arrastra, in its simplest terms is a grinder and dates back to the fifth century B.C.

The grinding surface is typically flat bedrock situated near a stream. A vertical pocket is drilled into the rock and a pole is placed in the pocket. Attached to the pole near its base is an arm and attached to the arm, usually by chains, are heavy drag stones. Farther up the pole is a long horizontal beam that is used to turn the center pole.

As the pole is rotated, the heavy drag stone do the grinding against the bedrock surface. Small arrastras could be human powered and draft animals were used to turn larger examples.

The most common use in Colorado was to grind ore containing gold flakes. The ore was placed on the grinding surface and after hours the ore is pulverized into a fine powder. A small amount of mercury is added during the process to amalgamate the gold.

The gold-mercury amalgam settles to the bedrock while the worthless rock is washed away using water from the nearby stream. The amalgam is then collected and strained through a cloth to remove most of the mercury leaving behind a gold button. The remaining mercury is driven off in a retort, condensed and reused. The gold requires further refining to remove the remaining impurities.

Arrastras were used in the absence of large, efficient gold mills or in remote locations. They are very limited in the amount of material that could be processed.

Arrastras in Colorado are rare. Many have been cut out of the bedrock and moved to museums. One example, still in its original location and relatively easy to reach, is north of Buena Vista on Fourmile Creek. It requires only a short walk from a four-wheel drive road.

To reach this arrastra, follow Colorado Avenue north from downtown Buena Vista. The road crosses the Arkansas River and becomes County Road 371. Within sight of the first Colorado Midland Railroad tunnel, County Road 375 heads east and uphill. After a mile, take County Road 376 to the right to Fourmile Creek.

This road has many washouts and it quite sandy -- it may require four-wheel drive. After crossing the creek, there is a small parking area on the right. By stepping over a wire fence (not posted) and walking west, there is a wide gravel wash. By following the wash down hill, the arrastra is at the edge of the trees at a distance of about 400 feet.

Kenneth Jessen has been a Loveland resident since 1965. He is an author of 18 books and more than 1,300 articles. He was an engineer for Hewlett-Packard for 33 years and now works as a full-time author, lecturer and guide.

Used to separate gold and silver from the land, mercury had to be exported from there to the new world until . . .

.[13] Such manifestations among hatters prompted several popular names for erethism, including "mad hatter disease",[11] "mad hatter syndrome",[14][15] "hatter's shakes" and "Danbury shakes".

.[13] Such manifestations among hatters prompted several popular names for erethism, including "mad hatter disease",[11] "mad hatter syndrome",[14][15] "hatter's shakes" and "Danbury shakes".