Costal Mts VS Basin & Range Thundereggs

Dec 25, 2017 14:00:02 GMT -5

Fossilman, amygdule, and 1 more like this

Post by 1dave on Dec 25, 2017 14:00:02 GMT -5

MIST - Mercury, iron, Sulfur, and Thundereggs.

(Fossilman - Mike, I think you and other TE lovers will like this history!)

Mercury and iron react readily with sulfur. Mercury amalgamates with most metals, but not iron.

That makes iron an excellent choice for mercury containers . . .

. . . But . . . how do they all inter-react in the formation of thundereggs?

Lots of mercury and sulfur = red cinnabar, Iron and sulfur = pyrite or marcasite on the coast.

More magnetite, hematite, limonite inland.

Lets check with the master on thundereggs - Richard Paul Colburn, the Geode Kid.

The following quotes (extended for those that want ALL of the information) and pictures are from his writings in the Geode Kid Free Club and his CD "The Formation of Thundereggs."

(Fossilman - Mike, I think you and other TE lovers will like this history!)

Mercury and iron react readily with sulfur. Mercury amalgamates with most metals, but not iron.

That makes iron an excellent choice for mercury containers . . .

. . . But . . . how do they all inter-react in the formation of thundereggs?

Lots of mercury and sulfur = red cinnabar, Iron and sulfur = pyrite or marcasite on the coast.

More magnetite, hematite, limonite inland.

Lets check with the master on thundereggs - Richard Paul Colburn, the Geode Kid.

The following quotes (extended for those that want ALL of the information) and pictures are from his writings in the Geode Kid Free Club and his CD "The Formation of Thundereggs."

(Page 3 for August, 2002)

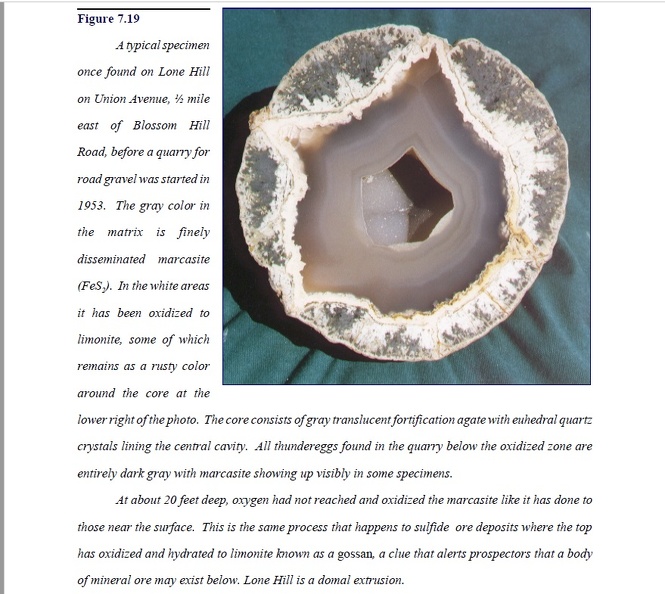

Lone Hill was a very unique geologic structure. It sat alone in the flat Santa Clara Valley about a mile east of Blossom Hill Road that skirted the eastern foothills of the sharply rising Santa Cruz Mountains. The hill was a single rhyolite volcano that extruded perlite interspersed with crystalline rhyolite lava about 20 million years ago. It had a cap rock of rhyolite forming a four to six foot rim around the northwest side of the hill otherwise, all other features hid any outcrop of thundereggs. The hill was only about 150 feet high by about one half mile long. It was a classic rhyolitic dome standing alone, a savanna island in a sea of fruit orchards and vineyards. One house was built on the north side near where Union Avenue made a Junction with a road going north. The only other inhabitants was the Mirassou Winery located on the flat adjacent to the west end of the hill. San Jose with 45,000 population in 1950 was out of sight 10 miles easterly. Los Gatos, a country town of 5000, was six miles to the northwest. Apart from that, the only territorial imperative was the symphony of summer bugs and an occasional car pulling into the winery to taste their vintages. I would never see that Lone Hill again.

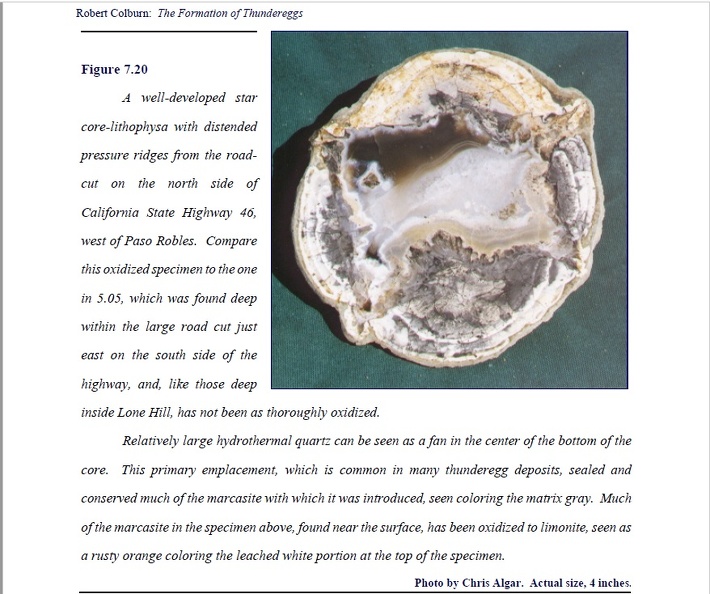

The Lone Hill thundereggs were rather dull compared to most, but they had their own beauty and as I was to discover, a uniqueness found in all Coast Range thundereggs, and not in any other western American geologic province:

They all contain the sulfide of iron, marcasite.

On the surface, most of the marcasite is rapidly oxidized to a rusty color of hematite and light yellow limonite.

(Page 5 for August,2002)

The next morning (1956), I went over to a lone round body of solid rhyolite. It was about ten feet in diameter and the only rock left. I wondered if this was the vent of the old volcano. It was a dark gray like the matrix in the thunderegg pictured above. It was also sprinkled throughout with tiny crystals of marcasite like that seen in the bottom quarter of the cavity of that egg. Though, the metallic luster can't be seen in that photo, it is quite identifiable as marcasite when viewed with a prospectors glass. The depth of the pit appeared to be no deeper than the valley floor outside of the periphery of the hill. Usually, rock quarries will go as deep as possible, but perhaps the bottom of the dome was reached in which case the mining would have run into the soft, useless sediment of the valley floor. Part of the pit had been used as an unofficial convenient trash dump.

I went over to a spot near the rock core and started digging into virgin clay which had a tan color.

The clay up near the edge of the pit was creamy white. Apparently, all the perlite had been altered very deep because there was no vitreous glassy remnants at all. Perhaps the San Francisco bay had once covered the entire hill and had altered the perlite to clay. The present elevation could not have been more than a hundred feet above sea level. However, with all this water to hydrate the perlite and decompose it to clay, the stony rhyolite an the thundereggs in the bottom of the pit were dark gray due to the presence of microscopic marcasite.

I dug a sack full in less than an hour, one of these was the biggest I had ever seen, about eight

inches in diameter. Most of them ranged from three to five inches. Then I went up near the top where the rim of the pit was near the original surface. I dug a few very nice round thundereggs out of the cream-white oxidized clay. They all had prominent pressure ridges which met at the star-points of the agate core.

After digging out a few, I broke one to see what they were like. They had the characteristic gray in their matrix, but much of the matrix had been oxidized and bleached white. The matrix was stained by oxidized marcasite on the contact with the translucent chalcedony core, and in the center of which was an attractive sparkling quartz crystal lined cavity.>>>>>>>>

The chalcedony was quite translucent, the faint wall lining bands could barely classify it as fortification agate, a name usually reserved for distinct contrasting band colors.

What was occurring to me, as I recalled that small San Luis Obispo thunderegg I bought many years earlier at the Minerals Unlimited rock shop in Berkeley, was how similar the matrix and agate was. Even the thundereggs I dug at John Hinkle Park in Berkeley were similar, all rather plain, but with much to say as I would discover later. When I got back to the pickup, I dug through my collection to get the San Luis Obispo egg, but I could not find it. Like all traveling nomads living in their vehicles, things are moved around “migrate” out of existence. I no longer

(Page 6 for August 2002)

had that egg. However, I would acquire one in the future and I find it appropriate to place a photo of it here as a proxy to demonstrate the similarities of the San Luis Obispo thundereggs to the ones I had just dug at Lone Hill. How I acquired it is another story for the future, but compare this specimen to those shown above, even oxidized iron shows its rusty stain in the matrix of the eggs dug near the surface.>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

While the Lone Hill thundereggs have a greener cast, I would find later that the gray in the egg at right is also microscopic marcasite. I made the connection when I went to dry-sand this specimen prior to polishing. Like the Lone Hill eggs, this one too gave off the tell tale pungent odor of sulfur dioxide. And so did all other thundereggs from the Coast Range Mountains, as I was later yet to discover, even some I had gotten from near the Umqua River in Oregon.

Why would all these Coast Range rhyolite lavas contain abundant sulfur when all the other rhyolites in the Basin & Range Province, Snake River Drainage, Columbia River and Colorado Plateaus yield chemical analysis of trace amounts of sulfur to none. All iron in those rhyolites are oxides, primarily magnetite which gives obsidian and perlite their black to gray colors. But magnetite, like marcasite, oxidizes when water hydrates perlite and lithophysae and turns them brownish-purple to tan and white. The reason why marcasite survives oxidation is that it is that emplaced by hydrothermal (hot water) solutions shortly or immediately after the flow had been extruded. Hydrothermal solutions have no oxygen, otherwise the marcasite would have been oxidized before it could be deposited. Indeed, it is sulfur that makes many ore deposits possible. The great quicksilver mines in the area have cinnabar, which is mercury sulfide, the primary ore of this element.

Meanwhile, I had all the eggs I could carry. The back of the pickup was filled with plaster of Paris figurines and I had to move the fragile merchandise back enough to get the eggs in. I said goodby to Mama Mirassou, she wished me back soon, but I knew after seeing the desecration to the land of my childhood, I would probably never go back, though I did in 1975. But that is another time for us to reach.

Lone Hill was a very unique geologic structure. It sat alone in the flat Santa Clara Valley about a mile east of Blossom Hill Road that skirted the eastern foothills of the sharply rising Santa Cruz Mountains. The hill was a single rhyolite volcano that extruded perlite interspersed with crystalline rhyolite lava about 20 million years ago. It had a cap rock of rhyolite forming a four to six foot rim around the northwest side of the hill otherwise, all other features hid any outcrop of thundereggs. The hill was only about 150 feet high by about one half mile long. It was a classic rhyolitic dome standing alone, a savanna island in a sea of fruit orchards and vineyards. One house was built on the north side near where Union Avenue made a Junction with a road going north. The only other inhabitants was the Mirassou Winery located on the flat adjacent to the west end of the hill. San Jose with 45,000 population in 1950 was out of sight 10 miles easterly. Los Gatos, a country town of 5000, was six miles to the northwest. Apart from that, the only territorial imperative was the symphony of summer bugs and an occasional car pulling into the winery to taste their vintages. I would never see that Lone Hill again.

The Lone Hill thundereggs were rather dull compared to most, but they had their own beauty and as I was to discover, a uniqueness found in all Coast Range thundereggs, and not in any other western American geologic province:

They all contain the sulfide of iron, marcasite.

On the surface, most of the marcasite is rapidly oxidized to a rusty color of hematite and light yellow limonite.

(Page 5 for August,2002)

The next morning (1956), I went over to a lone round body of solid rhyolite. It was about ten feet in diameter and the only rock left. I wondered if this was the vent of the old volcano. It was a dark gray like the matrix in the thunderegg pictured above. It was also sprinkled throughout with tiny crystals of marcasite like that seen in the bottom quarter of the cavity of that egg. Though, the metallic luster can't be seen in that photo, it is quite identifiable as marcasite when viewed with a prospectors glass. The depth of the pit appeared to be no deeper than the valley floor outside of the periphery of the hill. Usually, rock quarries will go as deep as possible, but perhaps the bottom of the dome was reached in which case the mining would have run into the soft, useless sediment of the valley floor. Part of the pit had been used as an unofficial convenient trash dump.

I went over to a spot near the rock core and started digging into virgin clay which had a tan color.

The clay up near the edge of the pit was creamy white. Apparently, all the perlite had been altered very deep because there was no vitreous glassy remnants at all. Perhaps the San Francisco bay had once covered the entire hill and had altered the perlite to clay. The present elevation could not have been more than a hundred feet above sea level. However, with all this water to hydrate the perlite and decompose it to clay, the stony rhyolite an the thundereggs in the bottom of the pit were dark gray due to the presence of microscopic marcasite.

I dug a sack full in less than an hour, one of these was the biggest I had ever seen, about eight

inches in diameter. Most of them ranged from three to five inches. Then I went up near the top where the rim of the pit was near the original surface. I dug a few very nice round thundereggs out of the cream-white oxidized clay. They all had prominent pressure ridges which met at the star-points of the agate core.

After digging out a few, I broke one to see what they were like. They had the characteristic gray in their matrix, but much of the matrix had been oxidized and bleached white. The matrix was stained by oxidized marcasite on the contact with the translucent chalcedony core, and in the center of which was an attractive sparkling quartz crystal lined cavity.>>>>>>>>

The chalcedony was quite translucent, the faint wall lining bands could barely classify it as fortification agate, a name usually reserved for distinct contrasting band colors.

What was occurring to me, as I recalled that small San Luis Obispo thunderegg I bought many years earlier at the Minerals Unlimited rock shop in Berkeley, was how similar the matrix and agate was. Even the thundereggs I dug at John Hinkle Park in Berkeley were similar, all rather plain, but with much to say as I would discover later. When I got back to the pickup, I dug through my collection to get the San Luis Obispo egg, but I could not find it. Like all traveling nomads living in their vehicles, things are moved around “migrate” out of existence. I no longer

(Page 6 for August 2002)

had that egg. However, I would acquire one in the future and I find it appropriate to place a photo of it here as a proxy to demonstrate the similarities of the San Luis Obispo thundereggs to the ones I had just dug at Lone Hill. How I acquired it is another story for the future, but compare this specimen to those shown above, even oxidized iron shows its rusty stain in the matrix of the eggs dug near the surface.>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

While the Lone Hill thundereggs have a greener cast, I would find later that the gray in the egg at right is also microscopic marcasite. I made the connection when I went to dry-sand this specimen prior to polishing. Like the Lone Hill eggs, this one too gave off the tell tale pungent odor of sulfur dioxide. And so did all other thundereggs from the Coast Range Mountains, as I was later yet to discover, even some I had gotten from near the Umqua River in Oregon.

Why would all these Coast Range rhyolite lavas contain abundant sulfur when all the other rhyolites in the Basin & Range Province, Snake River Drainage, Columbia River and Colorado Plateaus yield chemical analysis of trace amounts of sulfur to none. All iron in those rhyolites are oxides, primarily magnetite which gives obsidian and perlite their black to gray colors. But magnetite, like marcasite, oxidizes when water hydrates perlite and lithophysae and turns them brownish-purple to tan and white. The reason why marcasite survives oxidation is that it is that emplaced by hydrothermal (hot water) solutions shortly or immediately after the flow had been extruded. Hydrothermal solutions have no oxygen, otherwise the marcasite would have been oxidized before it could be deposited. Indeed, it is sulfur that makes many ore deposits possible. The great quicksilver mines in the area have cinnabar, which is mercury sulfide, the primary ore of this element.

Meanwhile, I had all the eggs I could carry. The back of the pickup was filled with plaster of Paris figurines and I had to move the fragile merchandise back enough to get the eggs in. I said goodby to Mama Mirassou, she wished me back soon, but I knew after seeing the desecration to the land of my childhood, I would probably never go back, though I did in 1975. But that is another time for us to reach.

(Page 2 for November 2002)

I would learn many years later that this unique hill was named Laton Point. It was a long oval, dome-shaped hill with an elevation of only about 150 feet above the flat expanse below its western side. You could see Burns and its sister city, Hines, a lumber mill town with its smoking wood waste incinerators twenty miles in the distance.

This huge vista was once a fresh water sea during the wetter ice ages, now reduced to a flat of sagebrush with remnant lakes scattered around of which Malheur Lake being the largest, and now a waterfowl refuge, a main stopping place for migratory birds. This basin covers about 7,500 square miles, which included Summer Lake and Lake Abet, that cold one I jumped in the day before. All other remnants are now dry alkali flats.

If one drives west from its ancient eastern shore at Buchanan and the foot of the Stinking Water Mountains on U.S. Hwy. 20 toward Bend for about 140 miles, you will come to a low pass where the sagebrush ends and the road drops suddenly into a forest of juniper trees and scrub pine. The desert just ends right there.

There is a historic geologic marker and a large drive out vista point along a 400 foot cliff. The marker is titled Dry River Canyon. It tells of a time that a river cut cliffs into the basalt plateau which was an outlet for this sea during the ice ages. There is no other explanation for such a deep canyon to exist with no river in it. That means that this basin once belonged to the Columbia Plateau drainage and the waters flowed to the Descuhtes River, and that to the Columbia River, thence to the Pacific Ocean, but now it is officially considered a part of the Great Basin which is adjoined to the Basin and Range Province.

All waters in this province no longer flow to the sea. The summit back near Hampton Station on Hwy. 20 is about 4400 feet. Sitting on top of this hill at 4370 feet, I would have been thirty feet under water! Buchanan and Burns would have been under more than 100 feet under water.

I got out and started poking around with my prospector’s pick. I walked northwesterly around a neck of rhyolite that crowned the hill. I found a small hole with a couple of egg sockets in what looked like dark green perlite. It was quite hard so I got my four pound “single jack” hammer and a couple of 18 x 3/4 inch gads, these have points rather than chisel ends that too many people try to use to break into hard rock. With the point ends,

(Page 3 for November 2002)

you can get a crack started and open it. You can drive another in where the crack runs and get a good bite on more real estate. Once a crack is opened, one can use a long bar to pry off what the gads have opened.

This perlite I was digging in was most uncooperative. It was cemented by silica from hydrothermal (hot water) solutions. It was hard getting a start, and when I thought I had a seam started, it broke off in small chunks.

But, with those sockets staring me in the face, I knew there would be thundereggs a few inches in. After about an hour, I got a good break running out a couple of feet, and about a foot back from the edge. I drove both gads, about six inches apart, down and a slab popped off exposing three nice looking thundereggs. They were sticking half way out, being the weak point for the slab of silicified perlite to peal off. They were so perfectly round and hard, that the perlite slab had sockets where it left the eggs as it fell free. I had this funny thought of collecting egg sockets from as many locations as possible. That funny little thought would be revisited one day when I started research on my CD “E-book” in 1997. For sake of proof, I do wish I had saved at least one socket, for it had the characteristic of “solid immiscibility,” that is, it looked like two incompatible solids. The surfaces of the eggs were so smooth, they were shiny, and so were the surfaces of the perlite. It reminded me of globules of oil in water.

One day, I would duplicate this phenomenon in an experiment. I got a small metal bucket and put about a quart of kerosene and water in it then poured liquid nitrogen over it. At first, I had an eruption of nitrogen “steam” pop out and I almost dropped the thermos bottle. So, I slowly poured the nitrogen in, stirring the water and kerosene to keep the two in a separated globular state until the water froze. When the kerosene was isolated into globules in the ice, I poured another thermos bottle full in and waited until the nitrogen settled into a simmer. I knew then, that the kerosene was also solid at minus 70 degrees because the liquid nitrogen is much colder than the melting point of kerosene. I grabbed the bucket with plenty of towels wrapped around my hands to protect them from flash freeze burns and banged it upside down and the steaming mass dropped on the concrete driveway. Instantly, I broke it with a hammer and behold!, I had kerosene “thundereggs” falling out, leaving sockets in the super frozen ice, which represented the perlite in my mind.

Though the experiment was successful, it would lead me somewhat astray because I was trying to duplicate what I thought happened in nature to form thundereggs. At that time, my theory required an immiscible globule in liquid perlite at about a thousand degrees centigrade, to be there and crystalize thus discharging dissolved gas that would open a cavity in the globule, much the same way air is discharged when water is frozen. When you put water in an ice cube tray, there are no bubbles in the water, but there sure are in ice cubes. And those fibrous, radial textures I had seen on many weathered thunderegg agate cores, or in empty thunderegg cavities, already had me convinced on how a star-shaped cavity could form when all the professionals and laymen alike, said that gas forming such a cavity in a lava was impossible.

Flawed in part as immiscibility happening at the level of producing such a globule in perlite, the hypothesis for the formation of star-shaped cavities was close enough for me to work this error out and come up with a more successful model of thunderegg formation.

With the valuable contributions from an Internet friend from Germany, Dr. Peter Woerner in Heidelberg sent me a paper written in Australia with a set of diagrams so similar to mine in my CD, I was shocked out of a dilemma as how to account for flow bands running from the lava and through the thundereggs in it and back out into the lava again, in perfect alignment. That, I realized, would be very difficult to account for.

As a result of this, and some encouraging data shared with me by another German, Dr. Gerhard Holzhey, a petrologist who uses photos of thundereggs for text references in his papers the same way I have done in my CD, I have “broken two eggs with one stone.” As a consequence, those of you who have my CD and are in my “Geode Kid Free Club” mailing list, will receive a free new set of diagrams to replace Figure 4.02 as soon as I finish them and some of the text.

(Page 4 for November, 2002)

Now, don’t think I have wandered too far from that hole I was digging in this cloudless day in June 1965. Rather, let this be an example of how my mind works. When I am alone in solitude digging thundereggs, my mind gets lost in a crowd of ideas. There was nobody around to tell me that this is wrong or that is crazy. And I had enough fun with the chemistry and physics of “energetic disassembly” in my school years that I could speak with relative authority before laymen about the science of the formation of perlite and the thundereggs in it.

After I got a few nice four to eight inch eggs out of that hole, I went around the west side of the rhyolite neck and found the caved tunnel of the cinnabar mine. It must have been a failure because the dumps showed only slight colorations of cinnabar and the mercury content would have been low. Just over the northeast side of the back end of the caved adit, was a hole dug full of top soil. I got in and cleaned it out. The perlite here was completely decomposed to a chalky clay. The digging was easy but nothing was showing. After cleaning it out a second time, my pick hit something solid and the muffled clank had me excited. I dug the dry clay away and a whopper appeared. I cleaned off the face of what I hit and this egg looked like it would exceed my 30-pound limit. After I got it out, I had to roll it up out of the hole. It was much more than a foot in diameter! This egg weighed at least eighty pounds. Wait until Helen sees this one, I was thinking. Then again, maybe she would object to my taking the others I already had.

Now, I had a moral dilemma: should I try to pay her for two days for one, or go spend my time trying to find those prized dark eggs with the white borderlines? Mavis told me she thought that they came from that first hole where I got those pithy green eggs at, but since I was at the top of the hill, I decided to try to dig some more big ones and trade or buy them for ten cents a pound from Helen Vickers. So, I cleaned out the hole again and it wasn’t more than half an hour that I had a second big one, not as big as the first, but quite respectable at about ten inches in diameter.>>>>>

Another larger one was just along to the right side of it. It was about a foot in diameter.

Then it occurred to me that this hole was only five feet from the caved in tunnel, and that if I

started a cut about eight feet below the in the side of the cave in, I would come into the side of the hole about four feet below the bottom of it. I would be able to shovel downhill into the caved tunnel and get a ton of eggs! But, if I did this now before seeing what Helen would do, I may needlessly be opening a great pocket for somebody else to profit from.

Besides that, I still wouldn’t know how good these big eggs are until I get them cut. I already had at least 250 pounds of eggs in this first day. So, I decided to fill the hole back up and wait another day after I find out what Helen would do. I would take the biggest one and the other smaller eggs I got out of the first hole, which would alone exceed thirty pounds. Then, I would pay for another permit the next day and use it up trying to find the borderline eggs. Then, I could take the rest of the big ones down to Helen and offer one of the big ones as a gesture of fairness and trust.

(Page 5 for November 2002)

That day was over, so I packed up the biggest one and left the two others buried in a secret place and headed back to Helen’s ranch house. Helen came out and I hollered “Why do these peacocks need help?” “Oh, they’re a noisy lot, ain’t they. Well, it looks like you got some nice ones.” she said watching the first ones I dug roll out of the sack. “Indeed, but I had to use this hammer,” waiving it in the air with one hand and a gad in the other, “but they are really stuck to the United States! What I needed was some dynamite, it took me three hours to get these out, but I bet they are good!” I exclaimed with a smile. Later, I was to find out just how good they were and I am placing one here as it relates to the map given below >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

“Where do you weigh them?” She looked at the pile and said “That looks like the limit, I don’t want to bother weighing them.” “But,” I hesitated, “I think I owe you something, I got one more” I let the tailgate down and rolled the big one out and thunk! It hit the ground. “Oh my heavens!” she gasped, “You’re the first to bring one this big to me!” she crowed delightfully, “Really?” I questioned, “You damn betcha, I have seen big ones before Ione started charging and giving permits, but I know people just steal them. I figure they think I might charge them extra or take them away, I don’t understand why people would steal a rock.”

She looked at and at me and said “Take it, I didn’t see it!” “ Well, thanks Mam, do you want a couple of these?” I pointed to the smaller pile, “Oh, I don’t know what I’d do with them,” “Well, wait a minute.” I followed quickly as I reached for a pair of polished Priday eggs stashed in my stock, “Here, you can put these in your front room, people love them.” I said as I handed them to her. “Oh, how beautiful those are, how nice and polished. Did you get these up there?” she pointed to the hill with the egg beds, “No, they come from the famous Priday Blue Bed over near Madras, keep them or give them away to some friend who likes thundereggs.” “Well, thank you, I never had any polished ones like this, I’ll put them on my mantel in the front room.” She was looking at the polished faces, “What did you put on these to make them shine so?” “Nothing,” I replied, “Those are polished on a machine like telescope mirrors. I mean that is the surface of the cut rock polished off.” I took out my pocket knife and dug at the surface, She cringed, “Don’t worry, agate is much harder than steel” I believe she was impressed.

Then there was two sonic booms BUM-BUM, in quick order, then HELP HELP Help Help, the peacocks were upset, but not as upset as Helen, “Damn the administration!” she hollered out, “Upsets the whole barnyard and the dogs too!” Wow, I thought, what a feisty woman this rancher is! A short, white contrail followed the jet plane, the only clue to where it was, a speck in the cloudless sky. “That’s a jet fighter,” I pointed it out, “I hear them all the time in the California deserts, there’s a lot of military air bases.” “Yeah, I hear more of them goddam things as time goes by, suppose were gonna get in a war with them damn Commies.” “I hope not,” I said, “there’s enough H-bombs to kill us all, that’s one reason I like it out here, its nuts in the city.” “Sure the hell is,” she

(Page 6 for November 2002)

agreed, “I have them city folks come out here and get stuck tryin’ to drive a car across the sagebrush, and they leave trash and whatnot, they’re nuts alright!”

It looked like we were going to get along fine. I asked her if she would give me a permit for tomorrow. “Why don’t you just go get what you want, and we can weigh them all when you are done?” I was shocked, “You mean you will trust me, I mean you don’t even know me.” I said with question marks popping out of my head, “Ain’t you the one that nearly croaked, I mean the kid Mavis said walked in half dead of thirst after walking clear down here a dozen or so many years ago?” “My God,” I exclaimed, “you heard about that?” I was quite surprised that such a small incident would be remembered, let alone being worth gossiping over. “That was news around here, not much happens out here around Buchanan, and some kid hitchhikin’ a thousand miles just for some thundereggs and damn near kills himself, is news enough. Now, you just go on and dig what you want, and if you get another big one like that,” pointing to the one that I rolled out of the truck, “it’ll look nice sittin’ by my front door.”

Then I chanced a question, “I have another one exposed in that hole by the cinnabar mine, I will dig that one out for you. Do you mind if I spend a few days up there? I’ll sign all the permits you need.” Was I ever hoping for her approval and she quickly answered, “Like I just said, when you are finished, just come by and we’ll settle up.” There could not have been a better answer. I felt like cracking a joke to Helen, so I followed up by telling her, “I want to thank you firstly for your trust. And secondly, I once saw a sign in a café where I worked in Portland, it said “HELEN BACK IS OUR CREDIT MANAGER, IF YOU WANT CREDIT, YOU WILL HAVE TO GO TO HELEN BACK” Now, I guess I can go dig eggs without having to go to Helen back every day.” She snickered and replied to the one star har-de har, “I told you, them city folks are nuts!, I’ll see you when you’ve got enough.”

She waved me on and walked back into her little neat white house through her menagerie of her noisy peacocks, chickens, goats and friendly dogs. This was so great, I had a carte blanch ticket to heaven!

Back on the hill, I punched an adit from the caved in cinnabar mine into the hole with the big ones. In one day I had half a truckload of big eggs, several were more than a foot in diameter. As I got down to about eight feet, the ground firmed up and it was like digging in rubber. The white clay just chipped away in small pieces and the pocket of eggs was only about twelve feet wide. After digging half way through the third day, I walked north on the road that forked north and south on the top of the hill. I found several small holes scattered about and chose the biggest one to dig in. The digging was easy and there were plenty of small, well silicified hard shelled eggs. They ran about two to four inches in diameter.

I broke a few and they were all very nice, some were solid agate with waterline agate suspensions within feathery hydrothermal chalcedony, and others had nice quartz crystal lined

cavities above waterline agate.>>>>>>

After about three hours, I had nearly a hundred pounds of these. This would be a good hole for saleable size thundereggs for rock shops. This pocket looked like it extended for some direction and it was more than four feet wide and easy digging. This would serve as my reserve, should I fail to find the black and white borderline eggs I

(Page 7 for November, 2002)

still wanted to find. I camped on top of the hill that night and thought about where they might be. I listened to Xrock 80 and watched as Burns and Hines lit up for the night.

There were very few lights showing between this hill and there. I watched the sparse headlights crawl along U.S. Highway 20 and wondered if this Paradise of Solitude would ever be lost to the God of Progress as I have seen taken forever from places in my childhood memories so many years ago. Every time I was in a place of peace, I remember my freedom in the country when I visited my Aunt and Uncle in Los Gatos, California. I always loved to go to the country, away from the city with all of its manic-depressive high life and strife. And I wondered yet again, like me, would some kid in the future be right here on this lone hill be told when he asks the Man, why? “Its Progress, kid, now stop playing in my sand pile, its for making concrete! I watched the bats until they dissolved in the fleeting dusk and I went to another dream.

I drove down the hill the next morning and started a serious hole down along a wall of black, glassy unaltered perlite. The old original hole was about twenty feet across. I recognized the place where I had dug when my father bought me here fourteen years ago. There were plenty of those broken green eggs lying about and the bank facing the road had some small ones showing in it. The perlite wall ran away from the road towards the south.

I figured that I would have at least eight feet to dig down until I reached virgin ground. I knew that this hole was dug first in the 1930s because my old friend in Oakland, Calvin Farrar, had some of those green ones, but he had some that had a darker green to almost brown shell. He said they came out of that same hole, and so did the couple of small black borderline eggs he had in his collection. He said he found the two left behind, but was sure that they came from this same hole because there were broken pieces of black matrix lying about. I looked at the black perlite ledge, but I saw no sockets in it. But it would make a good safe “hanging wall” to dig down along.

To my delight, I found virgin ground only four feet down. And it was full of good eggs! The hanging wall of perlite dipped to the west about ten degrees and the strike was to the south. The eggs closer to the perlite wall were darker brown and the most silicified. As I widened the hole about four feet, the eggs got greener and less silicified and now I was getting a “read” on this deposit. It appeared that there were a band of good eggs a little more than four feet wide. I deduced the probability of good eggs running the length of the perlite ledge which was about twenty feet long. I couldn’t understand why this hole was dug fifteen feet away from the perlite ledge, because all there was were those pithy green eggs. I saw a lot of those in collections and a few rock shops, but I didn’t like them because they were full of pits. I had one in my collection as a specimen, but they were not good to dig for wholesale to rock shops. They were junk.

After digging several nice eggs near the perlite wall, I saw a fracture seam running into the perlite which could give me a look into the perlite itself. It was near the bottom of where I was digging, so I gutted a small hole out along side of it and got my hammer and gads. I drove a gad into the seam and a pie shaped chunk of perlite broke off. I had difficulty pulling it up and I had to dig a little more decomposed perlite out. When I wedged it open, I saw two small egg sockets in it. I broke it up and threw the pieces out. I saw two black eggs half sticking out. I had to widen the hole down, getting good eggs in the clay on the way down. When the hole was wide enough so I could get a good bite angle over the top of the eggs, I hammered the gad in and popped both out. These sure looked promising and when I broke the golf ball sized one open, it was what I was looking for. I had found where the borderline thundereggs were. The other was twice the size of the first and I didn’t break it, I knew what I had!

There were never very many of these elusive eggs and I began to understand why. The chunks of perlite I removed had only exposed two. The perlite I removed must have weighed a hundred pounds with a volume of about a cubic foot. There were no eggs in it and the two in the wall were about eight inches apart. They were very

(Page 8 for November, 2002)

sparse. I got out of the hole and started driving the gads into the perlite ledge itself. I soon found out why there were never many of these fine thundereggs. That perlite was so hard, all the gad would do is chip it off into small pieces.

Perlite has what is called a “perlitic fracture.” That is, it has the nasty habit of breaking along small conchoidal clefts. Unless there was a natural break somewhere, it would be impossible to get anywhere with it. The only thing that would work, and it would work very well, would to be to drill a couple of holes about three feet deep in it and pop it with about half a stick of 40% dynamite. But, the only place you can buy dynamite was in Nevada and I don’t think Helen would be that liberal. It could be a sonic boom to her, but I was never to try it. There were enough excellent eggs in the clay four feet wide out from that perlite wall and when I was done assessing the length of the strike, I had about all the Buchanan eggs I could carry.

As it turned out, Helen got a big one and we estimated that I had half a ton dug over four days. So, I payed Helen a hundred bucks, but she would never again have me sign a permit. I planned to come back next year to get more and she didn’t object. But it wouldn’t become clear until two years later as to why she wouldn’t make me sign any permits. I went to Ione, the owner, and offered her a deal to do some serious mining and run the deposits as pay digs. That was the worst mistake I would ever make. But, lets save that one for now. Later that year, I had cut some of those eggs I got out of that slot along the perlite at Site 2 on the map below. I had plans to dig a shaft down along that perlite hanging wall and go as deep as possible. I knew I could make good money if I could get a few thousand pounds of eggs like this one! >>>>>>

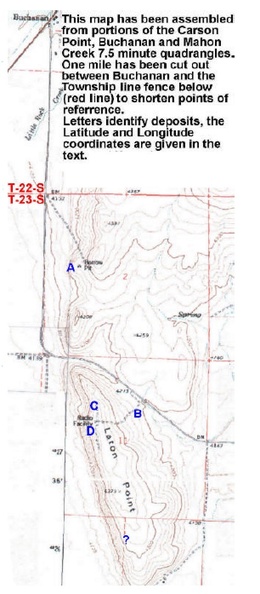

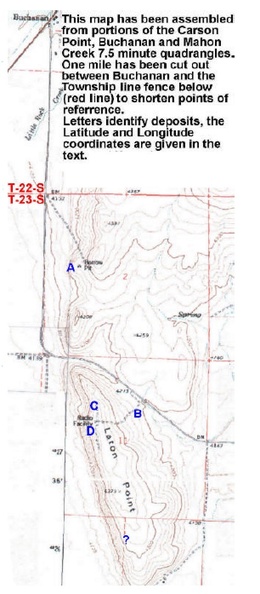

On page 9 below is a map with four sites labeled A, B, C and D. Site A is the Secret Ridge mine

that I discovered in 1967, but I didn’t mine it until 1968 when I built rock bins at Buchanan

Station and supplied the Oards with thundereggs and agate from many other deposits in Oregon.

I would also build rock bins at Burns Junction and Riley as well as supply rocks to the folks at

Brothers. These were like franchises where they would sell the rocks and I would come by after

a dig and resupply them and take half the money waiting for me. There may have been a future in

this for me, however, the Middle East oil embargo destroyed the business. You can’t drive hundreds of miles in a vehicle that gets twelve miles to the gallon and have the gasoline prices double. Between that and competing with cheap imported geodes from Mexico, I could not make a living on an already tight budget . So, I was forced to abandon my operations. But, like many bad things that happen in the now, turn out to be blessings in the future.

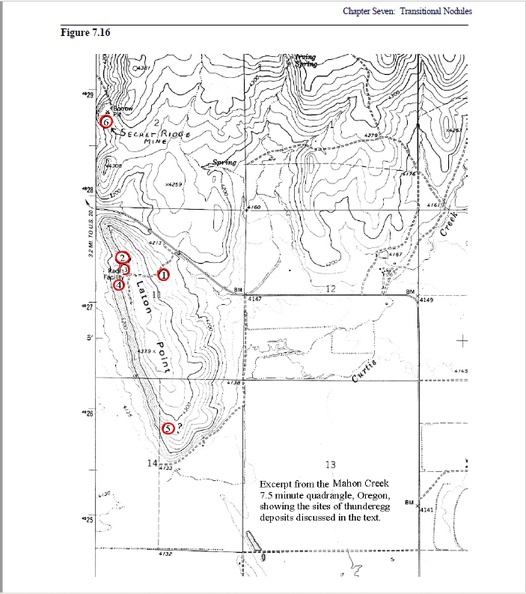

Below, you will be sharing a new experience with me. This will be a collection of 7.5 minute topographic maps on CD discs I have purchased from All Topo Maps. When a map is on my computer screen and I move the mouse, the cursor arrow activates a row of longitude and latitude numbers giving the exact location where the arrow points. I will still give the Section, Township and Range coordinates, but for those who have a Global Positioning Satellite device, I will be able to put you within 50 feet or better of a deposit or hole where I have dug at.

(Page 9 for November, 2002)

Site A is the Secret Ridge deposit I discovered in 1967. Its precise location is: N430 36.149,94', W1180 37.419,97' or as stated by Section, Township & Range (STR) the Secret Ridge is in the SW 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 2, T-23-S, R-33-E. in the Mahon Creek 7.5 minute

quadrangle. All following locations below are in the Mahon Creek quadrangle.

The Range is not printed on this excerpt, but they are printed on the top and bottom of each of these maps. Similarly, the thundereggs in the photos on pages 2 and 9 in this issue are from Site B, the precise location is N430 35.404', W1180 36.965,72' and the STR coordinates are in the SW 1/4 of the NE 1/4 of Section 11, T-23-S, R-33-E.

The thundereggs in the photo on page 7 in this issue are from Site C, the precise location is N430.410,73', W1180 367.284,37' and the STR coordinates are in the SE 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 11, T-22-S, R,-33-E.

The thundereggs on pages 5 and 6 are from site D, which are two of several pockets around the Radio Facility at N430 35.325,58', W1180 37.299,63' and the STR coordinates are in the SE 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 11 also.

There are isolated pockets of thundereggs at other places on this hill. In about 1975, a family member of Ione mined this deposit with a backhoe, however, I don’t think he ever dug out site B, which if it was left untouched, many fine thundereggs would remain. The last secret of that body of black perlite is, that when I got down to 10 feet deep, the perlite started to disappear and roll under in a manner that I could have driven a tunnel under it to the west and I don’t know what could be found under it. For sure, that if it was ever drilled and shot, not only could a lot of those black and white borderline eggs could be found, there is no telling what tonnage and quality could be mined. I do know, that the best thundereggs on this hill came from that slot I mined the next year. And I owe a debt of gratitude to both Helen Vickers, Mavis and Richard Oard for giving me a good start in an odyssey that would continue uninterrupted for the next 37 years, and I continue this today by saying I’ll see you next month. Then, I will take you into the stark beauty of one of the most fantastic places I have visited, Succor Creek Canyon State Park near the Idaho-Oregon State border.

If you see any typos or grammatical errors, please let me know so I can clean this up for the future.

(Page 10 for November, 2002)

June 1965. From Buchanan to Succor Creek: My first virgin deposit discovery.

Helen Vickers was stunned with the amount I had dug in the few days I was on Laton Point, that

famous dig I learned about more than a dozen years before from my old 83 year-old friend in Oakland, California, known as the Buchanan scenic thundereggs. The sites and people were just as scenic. Helen, never the one to hold her feelings undisclosed expressed to me, “You sure musta’ dug like a damned badger, did you leave any up there?,” she questioned me in vinegar jest, “Yep”, I replied, “I left one, its still in the hole.” She never laughed, but you could see the humor in her smile and sassy blue eyes. I had payed her a her ninety bucks, but she and I knew I had well in excess of a thousand pounds. She was pleased with the one footer I gave her for her front door ornament. I rolled it over to her door with my foot and suggested, “You can show that to your customers to prove that there are eggs up there.”

I told her that I would be back next year to sink a shaft at the first hole and thanked her for her

hospitality. My truck was filled to the gunnels with eggs. It was a three quarter ton, but it had a squashy feel with all those eggs plus the few hundred pounds of other gear and my polished collection. I felt great. I had been surprised by such great success. I had gotten four distinctly different type of eggs from that hill. You could tell from which hole they came from just by looking at them. I was thinking if it would be legitimate to claim four different locations for thundereggs from one single original rhyolite extrusion. I had assumed that this dome like hill was an eruption from the same magma chamber because the shells of all four shared a distinctly different textured matrix from any other thunderegg deposit I had in my collection, they all had a radial, fibrous texture.

However, since their colors and degree of silicification of the matrixes were distinctively different which had been acquired by different processes on that hill, I felt that this remarkable hill deserved having four locations listed. Indeed, the big eggs found by the mercury mine had traces of cinnabar color in the agate which I have never seen before in any other deposits, nor was this found at any of the other sites on this hill.

And in the future, another site would be discovered by a rancher on his property on the south end of the hill (See question mark on the map of the November issue, last page) and these had a dark red shell.

I would learn many years later that this unique hill was named Laton Point. It was a long oval, dome-shaped hill with an elevation of only about 150 feet above the flat expanse below its western side. You could see Burns and its sister city, Hines, a lumber mill town with its smoking wood waste incinerators twenty miles in the distance.

This huge vista was once a fresh water sea during the wetter ice ages, now reduced to a flat of sagebrush with remnant lakes scattered around of which Malheur Lake being the largest, and now a waterfowl refuge, a main stopping place for migratory birds. This basin covers about 7,500 square miles, which included Summer Lake and Lake Abet, that cold one I jumped in the day before. All other remnants are now dry alkali flats.

If one drives west from its ancient eastern shore at Buchanan and the foot of the Stinking Water Mountains on U.S. Hwy. 20 toward Bend for about 140 miles, you will come to a low pass where the sagebrush ends and the road drops suddenly into a forest of juniper trees and scrub pine. The desert just ends right there.

There is a historic geologic marker and a large drive out vista point along a 400 foot cliff. The marker is titled Dry River Canyon. It tells of a time that a river cut cliffs into the basalt plateau which was an outlet for this sea during the ice ages. There is no other explanation for such a deep canyon to exist with no river in it. That means that this basin once belonged to the Columbia Plateau drainage and the waters flowed to the Descuhtes River, and that to the Columbia River, thence to the Pacific Ocean, but now it is officially considered a part of the Great Basin which is adjoined to the Basin and Range Province.

All waters in this province no longer flow to the sea. The summit back near Hampton Station on Hwy. 20 is about 4400 feet. Sitting on top of this hill at 4370 feet, I would have been thirty feet under water! Buchanan and Burns would have been under more than 100 feet under water.

I got out and started poking around with my prospector’s pick. I walked northwesterly around a neck of rhyolite that crowned the hill. I found a small hole with a couple of egg sockets in what looked like dark green perlite. It was quite hard so I got my four pound “single jack” hammer and a couple of 18 x 3/4 inch gads, these have points rather than chisel ends that too many people try to use to break into hard rock. With the point ends,

(Page 3 for November 2002)

you can get a crack started and open it. You can drive another in where the crack runs and get a good bite on more real estate. Once a crack is opened, one can use a long bar to pry off what the gads have opened.

This perlite I was digging in was most uncooperative. It was cemented by silica from hydrothermal (hot water) solutions. It was hard getting a start, and when I thought I had a seam started, it broke off in small chunks.

But, with those sockets staring me in the face, I knew there would be thundereggs a few inches in. After about an hour, I got a good break running out a couple of feet, and about a foot back from the edge. I drove both gads, about six inches apart, down and a slab popped off exposing three nice looking thundereggs. They were sticking half way out, being the weak point for the slab of silicified perlite to peal off. They were so perfectly round and hard, that the perlite slab had sockets where it left the eggs as it fell free. I had this funny thought of collecting egg sockets from as many locations as possible. That funny little thought would be revisited one day when I started research on my CD “E-book” in 1997. For sake of proof, I do wish I had saved at least one socket, for it had the characteristic of “solid immiscibility,” that is, it looked like two incompatible solids. The surfaces of the eggs were so smooth, they were shiny, and so were the surfaces of the perlite. It reminded me of globules of oil in water.

One day, I would duplicate this phenomenon in an experiment. I got a small metal bucket and put about a quart of kerosene and water in it then poured liquid nitrogen over it. At first, I had an eruption of nitrogen “steam” pop out and I almost dropped the thermos bottle. So, I slowly poured the nitrogen in, stirring the water and kerosene to keep the two in a separated globular state until the water froze. When the kerosene was isolated into globules in the ice, I poured another thermos bottle full in and waited until the nitrogen settled into a simmer. I knew then, that the kerosene was also solid at minus 70 degrees because the liquid nitrogen is much colder than the melting point of kerosene. I grabbed the bucket with plenty of towels wrapped around my hands to protect them from flash freeze burns and banged it upside down and the steaming mass dropped on the concrete driveway. Instantly, I broke it with a hammer and behold!, I had kerosene “thundereggs” falling out, leaving sockets in the super frozen ice, which represented the perlite in my mind.

Though the experiment was successful, it would lead me somewhat astray because I was trying to duplicate what I thought happened in nature to form thundereggs. At that time, my theory required an immiscible globule in liquid perlite at about a thousand degrees centigrade, to be there and crystalize thus discharging dissolved gas that would open a cavity in the globule, much the same way air is discharged when water is frozen. When you put water in an ice cube tray, there are no bubbles in the water, but there sure are in ice cubes. And those fibrous, radial textures I had seen on many weathered thunderegg agate cores, or in empty thunderegg cavities, already had me convinced on how a star-shaped cavity could form when all the professionals and laymen alike, said that gas forming such a cavity in a lava was impossible.

Flawed in part as immiscibility happening at the level of producing such a globule in perlite, the hypothesis for the formation of star-shaped cavities was close enough for me to work this error out and come up with a more successful model of thunderegg formation.

With the valuable contributions from an Internet friend from Germany, Dr. Peter Woerner in Heidelberg sent me a paper written in Australia with a set of diagrams so similar to mine in my CD, I was shocked out of a dilemma as how to account for flow bands running from the lava and through the thundereggs in it and back out into the lava again, in perfect alignment. That, I realized, would be very difficult to account for.

As a result of this, and some encouraging data shared with me by another German, Dr. Gerhard Holzhey, a petrologist who uses photos of thundereggs for text references in his papers the same way I have done in my CD, I have “broken two eggs with one stone.” As a consequence, those of you who have my CD and are in my “Geode Kid Free Club” mailing list, will receive a free new set of diagrams to replace Figure 4.02 as soon as I finish them and some of the text.

(Page 4 for November, 2002)

Now, don’t think I have wandered too far from that hole I was digging in this cloudless day in June 1965. Rather, let this be an example of how my mind works. When I am alone in solitude digging thundereggs, my mind gets lost in a crowd of ideas. There was nobody around to tell me that this is wrong or that is crazy. And I had enough fun with the chemistry and physics of “energetic disassembly” in my school years that I could speak with relative authority before laymen about the science of the formation of perlite and the thundereggs in it.

After I got a few nice four to eight inch eggs out of that hole, I went around the west side of the rhyolite neck and found the caved tunnel of the cinnabar mine. It must have been a failure because the dumps showed only slight colorations of cinnabar and the mercury content would have been low. Just over the northeast side of the back end of the caved adit, was a hole dug full of top soil. I got in and cleaned it out. The perlite here was completely decomposed to a chalky clay. The digging was easy but nothing was showing. After cleaning it out a second time, my pick hit something solid and the muffled clank had me excited. I dug the dry clay away and a whopper appeared. I cleaned off the face of what I hit and this egg looked like it would exceed my 30-pound limit. After I got it out, I had to roll it up out of the hole. It was much more than a foot in diameter! This egg weighed at least eighty pounds. Wait until Helen sees this one, I was thinking. Then again, maybe she would object to my taking the others I already had.

Now, I had a moral dilemma: should I try to pay her for two days for one, or go spend my time trying to find those prized dark eggs with the white borderlines? Mavis told me she thought that they came from that first hole where I got those pithy green eggs at, but since I was at the top of the hill, I decided to try to dig some more big ones and trade or buy them for ten cents a pound from Helen Vickers. So, I cleaned out the hole again and it wasn’t more than half an hour that I had a second big one, not as big as the first, but quite respectable at about ten inches in diameter.>>>>>

Another larger one was just along to the right side of it. It was about a foot in diameter.

Then it occurred to me that this hole was only five feet from the caved in tunnel, and that if I

started a cut about eight feet below the in the side of the cave in, I would come into the side of the hole about four feet below the bottom of it. I would be able to shovel downhill into the caved tunnel and get a ton of eggs! But, if I did this now before seeing what Helen would do, I may needlessly be opening a great pocket for somebody else to profit from.

Besides that, I still wouldn’t know how good these big eggs are until I get them cut. I already had at least 250 pounds of eggs in this first day. So, I decided to fill the hole back up and wait another day after I find out what Helen would do. I would take the biggest one and the other smaller eggs I got out of the first hole, which would alone exceed thirty pounds. Then, I would pay for another permit the next day and use it up trying to find the borderline eggs. Then, I could take the rest of the big ones down to Helen and offer one of the big ones as a gesture of fairness and trust.

(Page 5 for November 2002)

That day was over, so I packed up the biggest one and left the two others buried in a secret place and headed back to Helen’s ranch house. Helen came out and I hollered “Why do these peacocks need help?” “Oh, they’re a noisy lot, ain’t they. Well, it looks like you got some nice ones.” she said watching the first ones I dug roll out of the sack. “Indeed, but I had to use this hammer,” waiving it in the air with one hand and a gad in the other, “but they are really stuck to the United States! What I needed was some dynamite, it took me three hours to get these out, but I bet they are good!” I exclaimed with a smile. Later, I was to find out just how good they were and I am placing one here as it relates to the map given below >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

“Where do you weigh them?” She looked at the pile and said “That looks like the limit, I don’t want to bother weighing them.” “But,” I hesitated, “I think I owe you something, I got one more” I let the tailgate down and rolled the big one out and thunk! It hit the ground. “Oh my heavens!” she gasped, “You’re the first to bring one this big to me!” she crowed delightfully, “Really?” I questioned, “You damn betcha, I have seen big ones before Ione started charging and giving permits, but I know people just steal them. I figure they think I might charge them extra or take them away, I don’t understand why people would steal a rock.”

She looked at and at me and said “Take it, I didn’t see it!” “ Well, thanks Mam, do you want a couple of these?” I pointed to the smaller pile, “Oh, I don’t know what I’d do with them,” “Well, wait a minute.” I followed quickly as I reached for a pair of polished Priday eggs stashed in my stock, “Here, you can put these in your front room, people love them.” I said as I handed them to her. “Oh, how beautiful those are, how nice and polished. Did you get these up there?” she pointed to the hill with the egg beds, “No, they come from the famous Priday Blue Bed over near Madras, keep them or give them away to some friend who likes thundereggs.” “Well, thank you, I never had any polished ones like this, I’ll put them on my mantel in the front room.” She was looking at the polished faces, “What did you put on these to make them shine so?” “Nothing,” I replied, “Those are polished on a machine like telescope mirrors. I mean that is the surface of the cut rock polished off.” I took out my pocket knife and dug at the surface, She cringed, “Don’t worry, agate is much harder than steel” I believe she was impressed.

Then there was two sonic booms BUM-BUM, in quick order, then HELP HELP Help Help, the peacocks were upset, but not as upset as Helen, “Damn the administration!” she hollered out, “Upsets the whole barnyard and the dogs too!” Wow, I thought, what a feisty woman this rancher is! A short, white contrail followed the jet plane, the only clue to where it was, a speck in the cloudless sky. “That’s a jet fighter,” I pointed it out, “I hear them all the time in the California deserts, there’s a lot of military air bases.” “Yeah, I hear more of them goddam things as time goes by, suppose were gonna get in a war with them damn Commies.” “I hope not,” I said, “there’s enough H-bombs to kill us all, that’s one reason I like it out here, its nuts in the city.” “Sure the hell is,” she

(Page 6 for November 2002)

agreed, “I have them city folks come out here and get stuck tryin’ to drive a car across the sagebrush, and they leave trash and whatnot, they’re nuts alright!”

It looked like we were going to get along fine. I asked her if she would give me a permit for tomorrow. “Why don’t you just go get what you want, and we can weigh them all when you are done?” I was shocked, “You mean you will trust me, I mean you don’t even know me.” I said with question marks popping out of my head, “Ain’t you the one that nearly croaked, I mean the kid Mavis said walked in half dead of thirst after walking clear down here a dozen or so many years ago?” “My God,” I exclaimed, “you heard about that?” I was quite surprised that such a small incident would be remembered, let alone being worth gossiping over. “That was news around here, not much happens out here around Buchanan, and some kid hitchhikin’ a thousand miles just for some thundereggs and damn near kills himself, is news enough. Now, you just go on and dig what you want, and if you get another big one like that,” pointing to the one that I rolled out of the truck, “it’ll look nice sittin’ by my front door.”

Then I chanced a question, “I have another one exposed in that hole by the cinnabar mine, I will dig that one out for you. Do you mind if I spend a few days up there? I’ll sign all the permits you need.” Was I ever hoping for her approval and she quickly answered, “Like I just said, when you are finished, just come by and we’ll settle up.” There could not have been a better answer. I felt like cracking a joke to Helen, so I followed up by telling her, “I want to thank you firstly for your trust. And secondly, I once saw a sign in a café where I worked in Portland, it said “HELEN BACK IS OUR CREDIT MANAGER, IF YOU WANT CREDIT, YOU WILL HAVE TO GO TO HELEN BACK” Now, I guess I can go dig eggs without having to go to Helen back every day.” She snickered and replied to the one star har-de har, “I told you, them city folks are nuts!, I’ll see you when you’ve got enough.”

She waved me on and walked back into her little neat white house through her menagerie of her noisy peacocks, chickens, goats and friendly dogs. This was so great, I had a carte blanch ticket to heaven!

Back on the hill, I punched an adit from the caved in cinnabar mine into the hole with the big ones. In one day I had half a truckload of big eggs, several were more than a foot in diameter. As I got down to about eight feet, the ground firmed up and it was like digging in rubber. The white clay just chipped away in small pieces and the pocket of eggs was only about twelve feet wide. After digging half way through the third day, I walked north on the road that forked north and south on the top of the hill. I found several small holes scattered about and chose the biggest one to dig in. The digging was easy and there were plenty of small, well silicified hard shelled eggs. They ran about two to four inches in diameter.

I broke a few and they were all very nice, some were solid agate with waterline agate suspensions within feathery hydrothermal chalcedony, and others had nice quartz crystal lined

cavities above waterline agate.>>>>>>

After about three hours, I had nearly a hundred pounds of these. This would be a good hole for saleable size thundereggs for rock shops. This pocket looked like it extended for some direction and it was more than four feet wide and easy digging. This would serve as my reserve, should I fail to find the black and white borderline eggs I

(Page 7 for November, 2002)

still wanted to find. I camped on top of the hill that night and thought about where they might be. I listened to Xrock 80 and watched as Burns and Hines lit up for the night.

There were very few lights showing between this hill and there. I watched the sparse headlights crawl along U.S. Highway 20 and wondered if this Paradise of Solitude would ever be lost to the God of Progress as I have seen taken forever from places in my childhood memories so many years ago. Every time I was in a place of peace, I remember my freedom in the country when I visited my Aunt and Uncle in Los Gatos, California. I always loved to go to the country, away from the city with all of its manic-depressive high life and strife. And I wondered yet again, like me, would some kid in the future be right here on this lone hill be told when he asks the Man, why? “Its Progress, kid, now stop playing in my sand pile, its for making concrete! I watched the bats until they dissolved in the fleeting dusk and I went to another dream.

I drove down the hill the next morning and started a serious hole down along a wall of black, glassy unaltered perlite. The old original hole was about twenty feet across. I recognized the place where I had dug when my father bought me here fourteen years ago. There were plenty of those broken green eggs lying about and the bank facing the road had some small ones showing in it. The perlite wall ran away from the road towards the south.

I figured that I would have at least eight feet to dig down until I reached virgin ground. I knew that this hole was dug first in the 1930s because my old friend in Oakland, Calvin Farrar, had some of those green ones, but he had some that had a darker green to almost brown shell. He said they came out of that same hole, and so did the couple of small black borderline eggs he had in his collection. He said he found the two left behind, but was sure that they came from this same hole because there were broken pieces of black matrix lying about. I looked at the black perlite ledge, but I saw no sockets in it. But it would make a good safe “hanging wall” to dig down along.

To my delight, I found virgin ground only four feet down. And it was full of good eggs! The hanging wall of perlite dipped to the west about ten degrees and the strike was to the south. The eggs closer to the perlite wall were darker brown and the most silicified. As I widened the hole about four feet, the eggs got greener and less silicified and now I was getting a “read” on this deposit. It appeared that there were a band of good eggs a little more than four feet wide. I deduced the probability of good eggs running the length of the perlite ledge which was about twenty feet long. I couldn’t understand why this hole was dug fifteen feet away from the perlite ledge, because all there was were those pithy green eggs. I saw a lot of those in collections and a few rock shops, but I didn’t like them because they were full of pits. I had one in my collection as a specimen, but they were not good to dig for wholesale to rock shops. They were junk.

After digging several nice eggs near the perlite wall, I saw a fracture seam running into the perlite which could give me a look into the perlite itself. It was near the bottom of where I was digging, so I gutted a small hole out along side of it and got my hammer and gads. I drove a gad into the seam and a pie shaped chunk of perlite broke off. I had difficulty pulling it up and I had to dig a little more decomposed perlite out. When I wedged it open, I saw two small egg sockets in it. I broke it up and threw the pieces out. I saw two black eggs half sticking out. I had to widen the hole down, getting good eggs in the clay on the way down. When the hole was wide enough so I could get a good bite angle over the top of the eggs, I hammered the gad in and popped both out. These sure looked promising and when I broke the golf ball sized one open, it was what I was looking for. I had found where the borderline thundereggs were. The other was twice the size of the first and I didn’t break it, I knew what I had!

There were never very many of these elusive eggs and I began to understand why. The chunks of perlite I removed had only exposed two. The perlite I removed must have weighed a hundred pounds with a volume of about a cubic foot. There were no eggs in it and the two in the wall were about eight inches apart. They were very

(Page 8 for November, 2002)

sparse. I got out of the hole and started driving the gads into the perlite ledge itself. I soon found out why there were never many of these fine thundereggs. That perlite was so hard, all the gad would do is chip it off into small pieces.

Perlite has what is called a “perlitic fracture.” That is, it has the nasty habit of breaking along small conchoidal clefts. Unless there was a natural break somewhere, it would be impossible to get anywhere with it. The only thing that would work, and it would work very well, would to be to drill a couple of holes about three feet deep in it and pop it with about half a stick of 40% dynamite. But, the only place you can buy dynamite was in Nevada and I don’t think Helen would be that liberal. It could be a sonic boom to her, but I was never to try it. There were enough excellent eggs in the clay four feet wide out from that perlite wall and when I was done assessing the length of the strike, I had about all the Buchanan eggs I could carry.

As it turned out, Helen got a big one and we estimated that I had half a ton dug over four days. So, I payed Helen a hundred bucks, but she would never again have me sign a permit. I planned to come back next year to get more and she didn’t object. But it wouldn’t become clear until two years later as to why she wouldn’t make me sign any permits. I went to Ione, the owner, and offered her a deal to do some serious mining and run the deposits as pay digs. That was the worst mistake I would ever make. But, lets save that one for now. Later that year, I had cut some of those eggs I got out of that slot along the perlite at Site 2 on the map below. I had plans to dig a shaft down along that perlite hanging wall and go as deep as possible. I knew I could make good money if I could get a few thousand pounds of eggs like this one! >>>>>>

On page 9 below is a map with four sites labeled A, B, C and D. Site A is the Secret Ridge mine

that I discovered in 1967, but I didn’t mine it until 1968 when I built rock bins at Buchanan

Station and supplied the Oards with thundereggs and agate from many other deposits in Oregon.

I would also build rock bins at Burns Junction and Riley as well as supply rocks to the folks at

Brothers. These were like franchises where they would sell the rocks and I would come by after

a dig and resupply them and take half the money waiting for me. There may have been a future in

this for me, however, the Middle East oil embargo destroyed the business. You can’t drive hundreds of miles in a vehicle that gets twelve miles to the gallon and have the gasoline prices double. Between that and competing with cheap imported geodes from Mexico, I could not make a living on an already tight budget . So, I was forced to abandon my operations. But, like many bad things that happen in the now, turn out to be blessings in the future.

Below, you will be sharing a new experience with me. This will be a collection of 7.5 minute topographic maps on CD discs I have purchased from All Topo Maps. When a map is on my computer screen and I move the mouse, the cursor arrow activates a row of longitude and latitude numbers giving the exact location where the arrow points. I will still give the Section, Township and Range coordinates, but for those who have a Global Positioning Satellite device, I will be able to put you within 50 feet or better of a deposit or hole where I have dug at.

(Page 9 for November, 2002)

Site A is the Secret Ridge deposit I discovered in 1967. Its precise location is: N430 36.149,94', W1180 37.419,97' or as stated by Section, Township & Range (STR) the Secret Ridge is in the SW 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 2, T-23-S, R-33-E. in the Mahon Creek 7.5 minute

quadrangle. All following locations below are in the Mahon Creek quadrangle.

The Range is not printed on this excerpt, but they are printed on the top and bottom of each of these maps. Similarly, the thundereggs in the photos on pages 2 and 9 in this issue are from Site B, the precise location is N430 35.404', W1180 36.965,72' and the STR coordinates are in the SW 1/4 of the NE 1/4 of Section 11, T-23-S, R-33-E.

The thundereggs in the photo on page 7 in this issue are from Site C, the precise location is N430.410,73', W1180 367.284,37' and the STR coordinates are in the SE 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 11, T-22-S, R,-33-E.

The thundereggs on pages 5 and 6 are from site D, which are two of several pockets around the Radio Facility at N430 35.325,58', W1180 37.299,63' and the STR coordinates are in the SE 1/4 of the NW 1/4 of Section 11 also.

There are isolated pockets of thundereggs at other places on this hill. In about 1975, a family member of Ione mined this deposit with a backhoe, however, I don’t think he ever dug out site B, which if it was left untouched, many fine thundereggs would remain. The last secret of that body of black perlite is, that when I got down to 10 feet deep, the perlite started to disappear and roll under in a manner that I could have driven a tunnel under it to the west and I don’t know what could be found under it. For sure, that if it was ever drilled and shot, not only could a lot of those black and white borderline eggs could be found, there is no telling what tonnage and quality could be mined. I do know, that the best thundereggs on this hill came from that slot I mined the next year. And I owe a debt of gratitude to both Helen Vickers, Mavis and Richard Oard for giving me a good start in an odyssey that would continue uninterrupted for the next 37 years, and I continue this today by saying I’ll see you next month. Then, I will take you into the stark beauty of one of the most fantastic places I have visited, Succor Creek Canyon State Park near the Idaho-Oregon State border.

If you see any typos or grammatical errors, please let me know so I can clean this up for the future.

(Page 10 for November, 2002)

June 1965. From Buchanan to Succor Creek: My first virgin deposit discovery.

Helen Vickers was stunned with the amount I had dug in the few days I was on Laton Point, that

famous dig I learned about more than a dozen years before from my old 83 year-old friend in Oakland, California, known as the Buchanan scenic thundereggs. The sites and people were just as scenic. Helen, never the one to hold her feelings undisclosed expressed to me, “You sure musta’ dug like a damned badger, did you leave any up there?,” she questioned me in vinegar jest, “Yep”, I replied, “I left one, its still in the hole.” She never laughed, but you could see the humor in her smile and sassy blue eyes. I had payed her a her ninety bucks, but she and I knew I had well in excess of a thousand pounds. She was pleased with the one footer I gave her for her front door ornament. I rolled it over to her door with my foot and suggested, “You can show that to your customers to prove that there are eggs up there.”

I told her that I would be back next year to sink a shaft at the first hole and thanked her for her

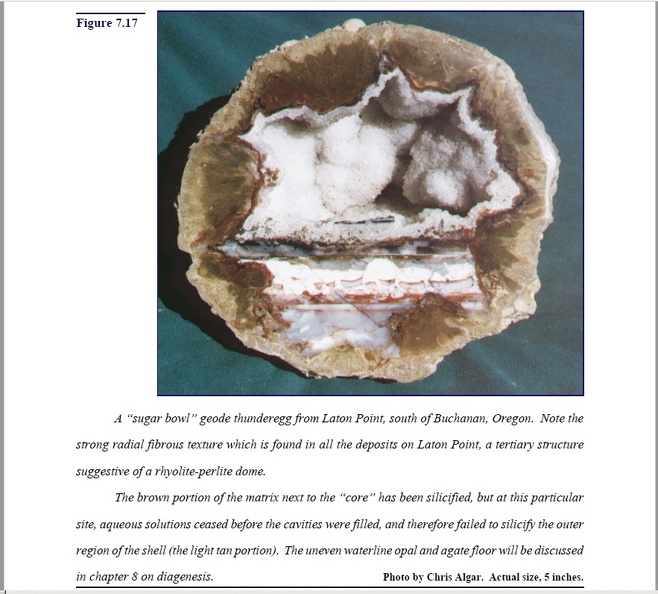

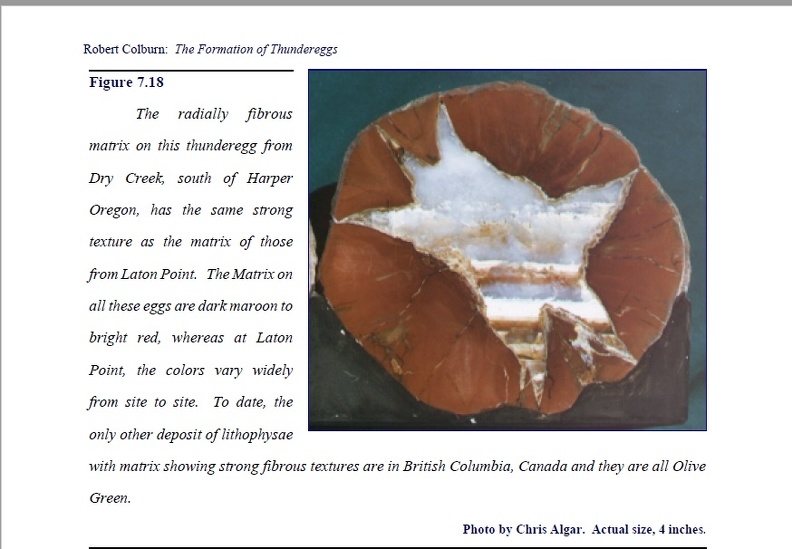

hospitality. My truck was filled to the gunnels with eggs. It was a three quarter ton, but it had a squashy feel with all those eggs plus the few hundred pounds of other gear and my polished collection. I felt great. I had been surprised by such great success. I had gotten four distinctly different type of eggs from that hill. You could tell from which hole they came from just by looking at them. I was thinking if it would be legitimate to claim four different locations for thundereggs from one single original rhyolite extrusion. I had assumed that this dome like hill was an eruption from the same magma chamber because the shells of all four shared a distinctly different textured matrix from any other thunderegg deposit I had in my collection, they all had a radial, fibrous texture.

However, since their colors and degree of silicification of the matrixes were distinctively different which had been acquired by different processes on that hill, I felt that this remarkable hill deserved having four locations listed. Indeed, the big eggs found by the mercury mine had traces of cinnabar color in the agate which I have never seen before in any other deposits, nor was this found at any of the other sites on this hill.

And in the future, another site would be discovered by a rancher on his property on the south end of the hill (See question mark on the map of the November issue, last page) and these had a dark red shell.