|

|

Post by 1dave on Jan 6, 2019 14:45:10 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by 1dave on Jan 6, 2019 15:23:48 GMT -5

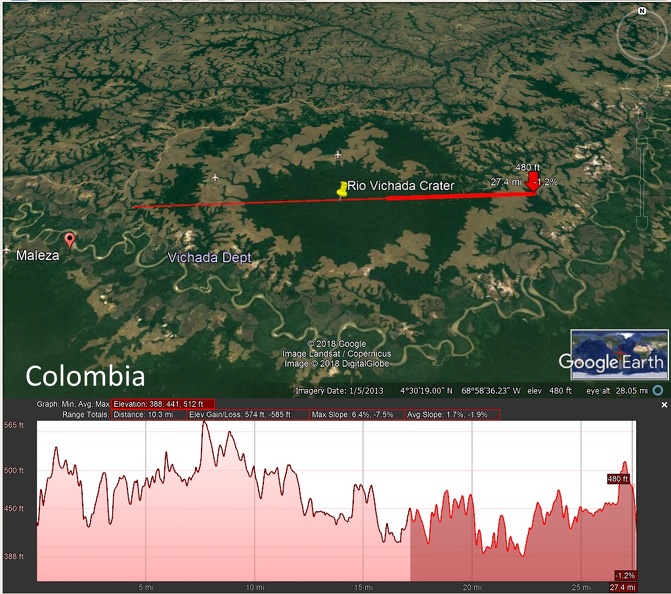

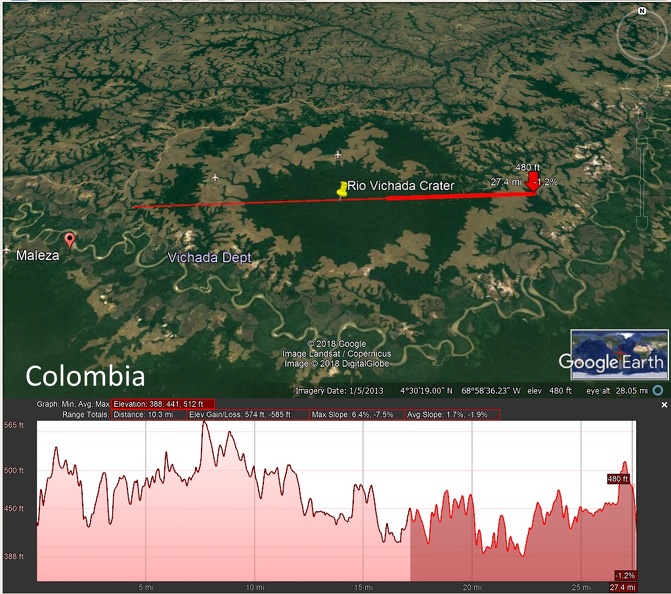

Vichada - the Largest crater in South America.  |

|

|

|

Post by grumpybill on Jan 6, 2019 19:09:02 GMT -5

Thanks, Dave.

Saved for later reading.

|

|

|

|

Post by 1dave on Jan 6, 2019 21:10:55 GMT -5

Asteroids that hit in the ocean, asteroids that brought chlorine and made the oceans salty, 5 days of presentations!

|

|

|

|

Post by 1dave on Jan 6, 2019 23:45:14 GMT -5

pubs.geoscienceworld.org/eurjmin/article-abstract/21/1/203/69343/characterisation-of-ballen-quartz-and-cristobalite?redirectedFrom=fulltext pubs.geoscienceworld.org/eurjmin/article-abstract/21/1/203/69343/characterisation-of-ballen-quartz-and-cristobalite?redirectedFrom=fulltextCharacterisation of ballen quartz and cristobalite in impact breccias: new observations and constraints on ballen formation Ludovic Ferrière Christian Koeberl Wolf Uwe Reimold European Journal of Mineralogy (2009) 21 (1): 203-217. doi.org/10.1127/0935-1221/2009/0021-1898Article history Cite Share Icon Share Tools Icon Tools Search Abstract Ballen quartz and cristobalite in impactite samples from five impact structures (Bosumtwi, Chicxulub, Mien, Ries, and Rochechouart) were investigated by optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), cathodoluminescence (CL), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Raman spectroscopy to better understand ballen formation. The occurrence of so-called “ballen quartz” has been reported from about one in five of the known terrestrial impact structures, mostly from clasts in impact melt rock and, more rarely, in suevite. “Ballen silica”, with either α-quartz or α-cristobalite structure, occurs as independent clasts or within diaplectic quartz glass or lechatelierite inclusions. Ballen are more or less spheroidal, in some cases elongate (ovoid) bodies that range in size from 8 to 214 μm, and either intersect or penetrate each other or abut each other. Based mostly on optical microscopic observations and Raman spectroscopy, we distinguish five types of ballen silica: α-cristobalite ballen with homogeneous extinction (type I); ballen α-quartz with homogeneous extinction (type II), with heterogeneous extinction (type III), and with intraballen recrystallisation (type IV); chert-like recristallized ballen α-quartz (type V). For the first time, coesite has been identified within ballen silica – in the form of tiny inclusions and exclusively within ballen of type I. The formation of ballen involves an impact-triggered solid-solid transition from α-quartz to diaplectic quartz glass, followed by the formation at high temperature of ballen of β-cristobalite and/or β-quartz, and finally back-transformation to α-cristobalite and/or α-quartz; or a solid-liquid transition from quartz to lechatelierite followed by nucleation and crystal growth at high temperature. The different types of ballen silica are interpreted as the result of back-transformation of β-cristobalite and/or β-quartz to α-cristobalite and/or to α-quartz with time. In nature, ballen silica has not been found anywhere else but associated with impact structures and, thus, these features could be added to the list of impact-diagnostic criteria. GeoRef Subject Chicxulub Crater Central Europe Africa Bosumtwi Crater Germany metamorphism Ghana lechatelierite Scandinavia silica minerals silicates metamorphic rocks cristobalite Bavaria Germany France impactites Europe impact breccia framework silicates suevite Ries Crater Rochechouart Crater West Africa Western Europe quartz Sweden |

|

|

|

Post by 1dave on Jan 7, 2019 1:27:58 GMT -5

PALEOENVIRONMENTAL CHARTS FOR TERRESTRIAL IMPACT STRUCTURES - A SIMPLE TOOL TO TEST IMPACT AGES AND MARINE/CONTINENTAL IMPACT CONDITIONS. M. Schmieder1 and E. Buchner, Institut für Planetologie, Universität Stuttgart, Herdweg 51, D-70174 Stuttgart, Germany; 1martin.schmieder@geologie.uni-stuttgart.de  |

|