Post by 1dave on Feb 12, 2019 20:59:15 GMT -5

The Strange Story of Silver Reef.

This story officially had it’s beginning with Sgt Orson Bennett Adams (B. 9 March 1815 Alexander, Genessee County, New York, Death: 4 February 1901 Leeds, Washington County, Utah) He was a veteran of the Mormon Battalion in 1846 during the Mexican American War. After finally reaching and building a home in Salt Lake City his family was asked by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints to join the “Iron Mission” to southwestern Utah. They agreed and were among the original settlers in the new town of Parowan in 1851.

In 1861 The Adams family with nine other families were requested by the Church to move again and establish another new town over fifty miles further south at the confluence of Leeds and Quail Creeks where hopefully they could survive. There Orson selected the most western 200 acres on Quail Creek for his home. The new settlement was named Harrisburg after one of their leaders, Moses Harris, who had previously established a Mormon colony near San Bernardino, California.

Willard G. McMullin, a master stone mason, arrived a year later in 1862 and constructed the Adams home, as well as many of the other residences of Harrisburg. From 1864 until the early 1890s, Orson B. Adams, his wife Susannah, two sons, and eventually two granddaughters lived in this small two-room sandstone dwelling.

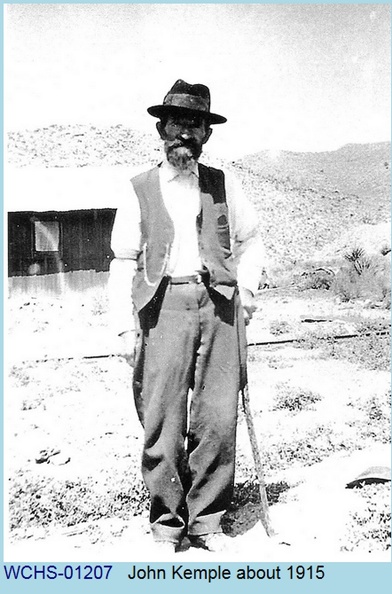

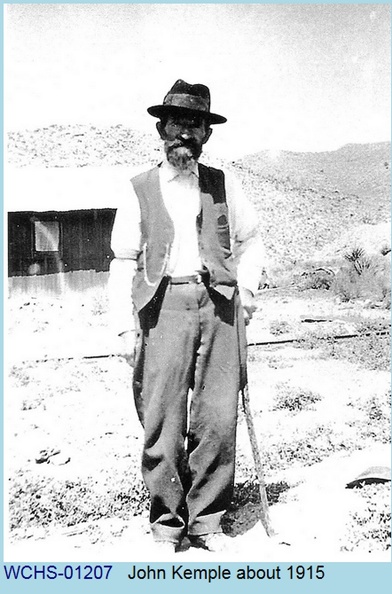

The next person pertinent to the Silver Reef story was John Kemple (1835 – 1918), the son of George Kemple and Hannah Foster. According to his grandson, James Kemple, John left home at the age of fifteen, and like many others, ended up in California with the Gold rush. He followed new camp after new camp without success.

To survive he learned how to assay.

John Kemple even joined the rush to Alaska and the Klondike gold fields. One year in Alaska he was so far north that winter caught his party on the polar ice pack. They would have starved, except that he discovered a mammoth, frozen in the ice. They managed to dig in far enough to cut meat from the pre-historic beast and eat it. He told also of another, smaller figure, deeper in the ice, which he said looked like a human. A few years later he tried to lead a scientific expedition back to the place, but couldn't find it again.

In 1866 John “took a room for the winter” at the two room Harrisburg home of Orson Adams. While wandering the nearby ledges south and west of the home he noticed some green and blue copper stains in the rocks. Assaying one of the samples of black "float," he found $17,000/ton amounts of silver was present! He sent ore samples to other assayers for conformation.

H. H. Smith, of Shaunty, Beaver County Utah said: “Kemple must be crazy to ask me to assay a sand rock.”

John spent several years trying to convince other miners that silver could indeed be found in sandstone and petrified wood, but to no avail. He finally gave up and joined the silver rush to White Pine Nevada, but returned in 1874 to record his first claim at Silver Reef as follows:

“said location commencing at a monument and notice placed on the ledge about three hundred yards southwest of O.B. Adam‟s house (Harrisburg) and running from thence in a northerly direction (1500) feet. This ledge shall be known as the Pride of the West Ledge and the Kemple Company. Location June the 18th, 1874. - Recorded June 26, 1874. Locator – John Kemple”

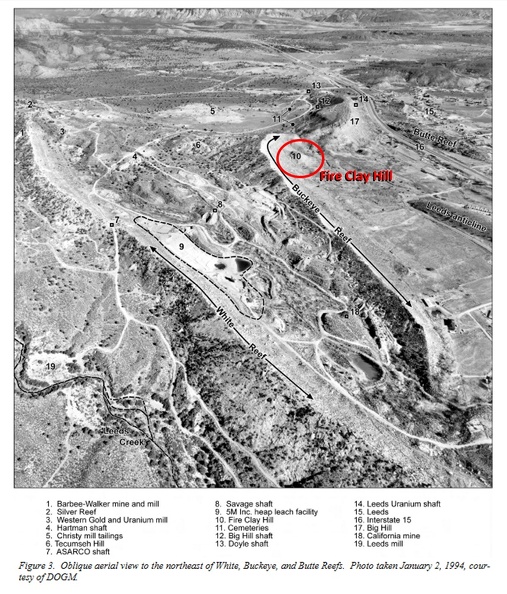

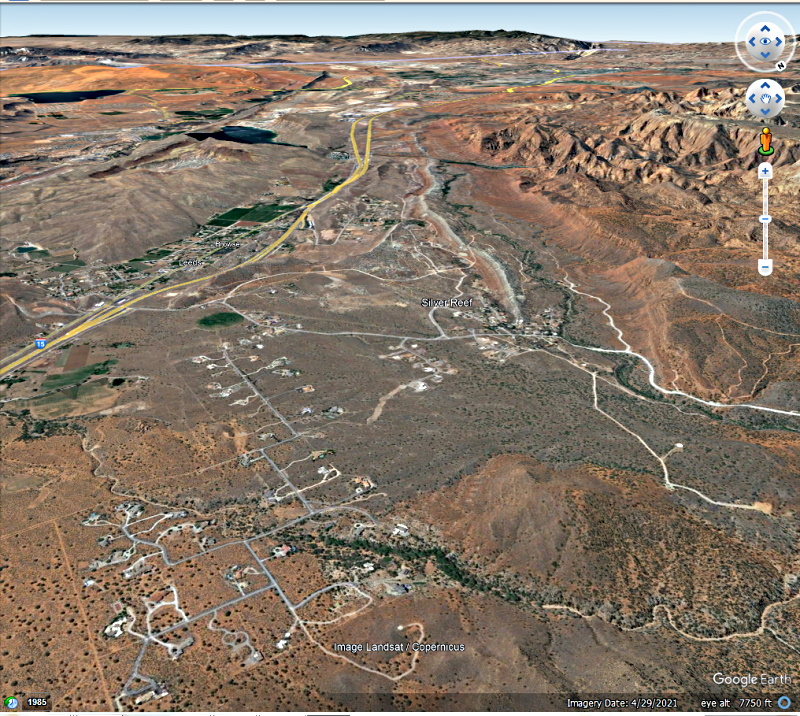

Yellow Pin (1) the Adams home, then pins headed south toward St. George of (2) the Pride of the west Mine, and (3) site of Kemple's first silver discovery.

ALL of these locations are about 3 miles southwest of the main Silver Reef mining areas, so there is still a lot of silver left today in the surrounding sandstone.

Kemple was getting old and little work was ever done at his mine.

On reading the above, I contacted Leslie Hale who quickly responded by tracking down 16 Silver Reef specimens that had been sent to the Smithsonian and photographed them with her phone to get them to me quickly.

Thank you Leslie!

The first image is of a specimen purchased from John Kemble himself.

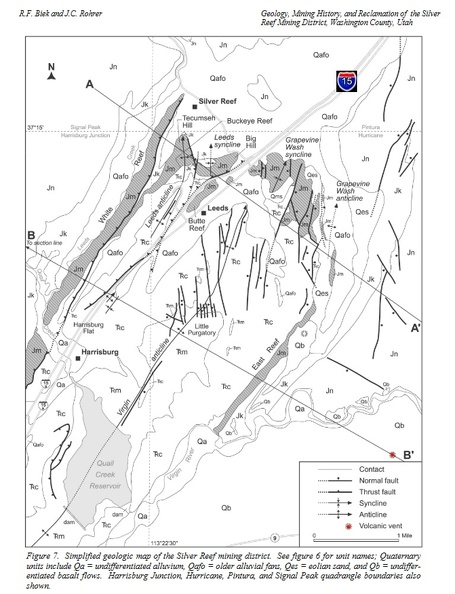

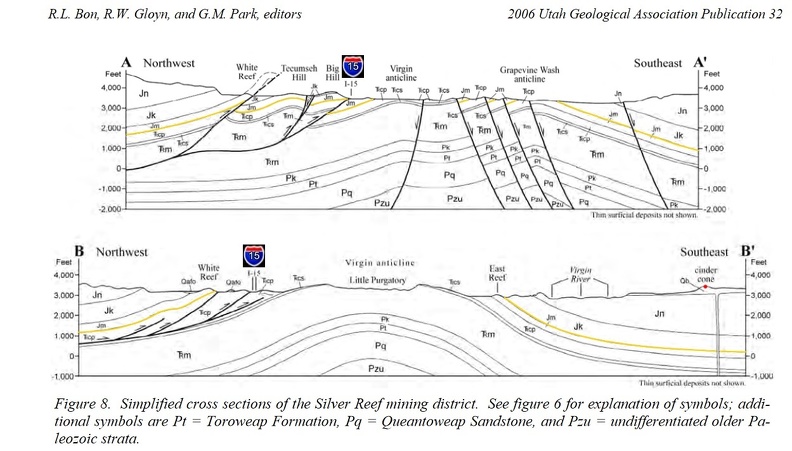

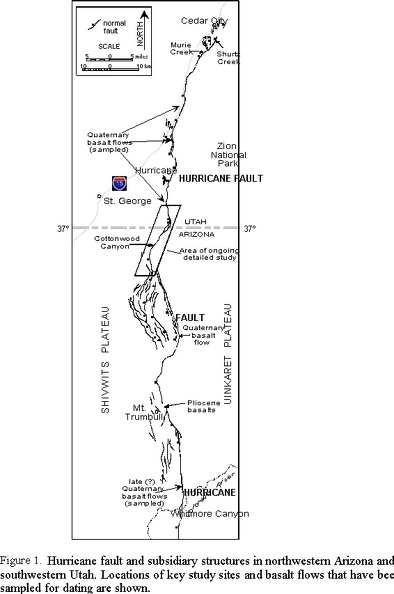

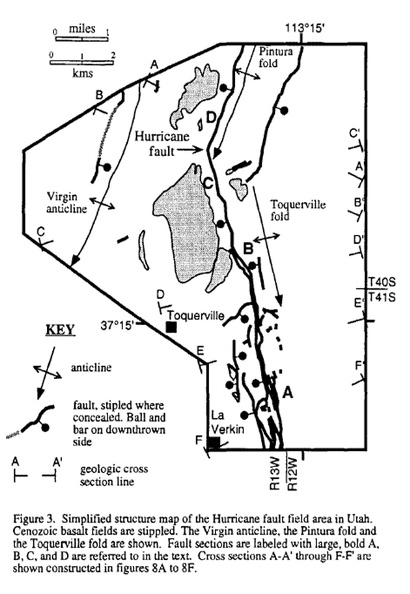

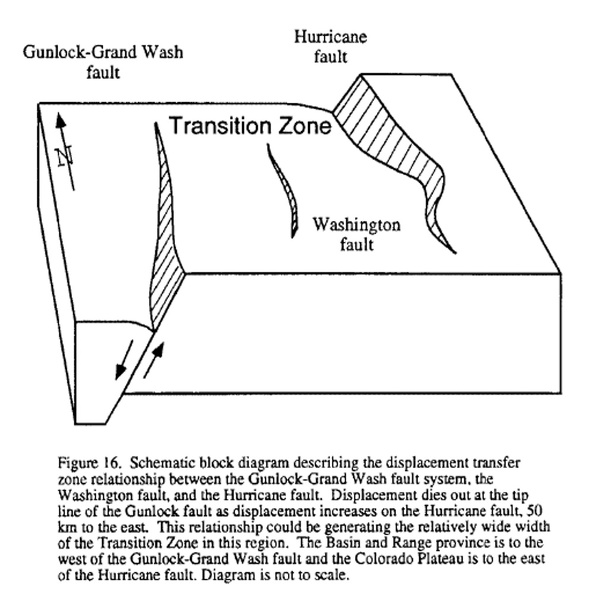

All of the silver has been found west of the Hurricane Fault. The sandstone layer full of petrified wood continues on to the east of the fault but little if any silver has ever been found there.

Now the question becomes: "Where did the silver come from"?

This story officially had it’s beginning with Sgt Orson Bennett Adams (B. 9 March 1815 Alexander, Genessee County, New York, Death: 4 February 1901 Leeds, Washington County, Utah) He was a veteran of the Mormon Battalion in 1846 during the Mexican American War. After finally reaching and building a home in Salt Lake City his family was asked by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints to join the “Iron Mission” to southwestern Utah. They agreed and were among the original settlers in the new town of Parowan in 1851.

In 1861 The Adams family with nine other families were requested by the Church to move again and establish another new town over fifty miles further south at the confluence of Leeds and Quail Creeks where hopefully they could survive. There Orson selected the most western 200 acres on Quail Creek for his home. The new settlement was named Harrisburg after one of their leaders, Moses Harris, who had previously established a Mormon colony near San Bernardino, California.

Willard G. McMullin, a master stone mason, arrived a year later in 1862 and constructed the Adams home, as well as many of the other residences of Harrisburg. From 1864 until the early 1890s, Orson B. Adams, his wife Susannah, two sons, and eventually two granddaughters lived in this small two-room sandstone dwelling.

The next person pertinent to the Silver Reef story was John Kemple (1835 – 1918), the son of George Kemple and Hannah Foster. According to his grandson, James Kemple, John left home at the age of fifteen, and like many others, ended up in California with the Gold rush. He followed new camp after new camp without success.

To survive he learned how to assay.

John Kemple even joined the rush to Alaska and the Klondike gold fields. One year in Alaska he was so far north that winter caught his party on the polar ice pack. They would have starved, except that he discovered a mammoth, frozen in the ice. They managed to dig in far enough to cut meat from the pre-historic beast and eat it. He told also of another, smaller figure, deeper in the ice, which he said looked like a human. A few years later he tried to lead a scientific expedition back to the place, but couldn't find it again.

In 1866 John “took a room for the winter” at the two room Harrisburg home of Orson Adams. While wandering the nearby ledges south and west of the home he noticed some green and blue copper stains in the rocks. Assaying one of the samples of black "float," he found $17,000/ton amounts of silver was present! He sent ore samples to other assayers for conformation.

H. H. Smith, of Shaunty, Beaver County Utah said: “Kemple must be crazy to ask me to assay a sand rock.”

John spent several years trying to convince other miners that silver could indeed be found in sandstone and petrified wood, but to no avail. He finally gave up and joined the silver rush to White Pine Nevada, but returned in 1874 to record his first claim at Silver Reef as follows:

“said location commencing at a monument and notice placed on the ledge about three hundred yards southwest of O.B. Adam‟s house (Harrisburg) and running from thence in a northerly direction (1500) feet. This ledge shall be known as the Pride of the West Ledge and the Kemple Company. Location June the 18th, 1874. - Recorded June 26, 1874. Locator – John Kemple”

Yellow Pin (1) the Adams home, then pins headed south toward St. George of (2) the Pride of the west Mine, and (3) site of Kemple's first silver discovery.

ALL of these locations are about 3 miles southwest of the main Silver Reef mining areas, so there is still a lot of silver left today in the surrounding sandstone.

Kemple was getting old and little work was ever done at his mine.

The third person pertinent to the Silver Reef story was William Tecumseh Barbee who finally started the silver rush that moved the town of Pioche Nevada to Silver Reef after noticing a rich layer of horn silver uncovered by a passing wagon wheel. That hill 3 1/4 miles northeast of Kemple's mine, which he named "Tecumseh Hill," was rich in silver chlorides. In the next 10 years miners removed over seven million dollars worth of the stuff that couldn't possibly be there.

On February 7, 1876, he (Barbee) wrote:

This sandstone country beats all the boys, and it is amusing to see how excited they get when they go round to see the sheets of silver which are exposed all over the different reefs . . . This is the most unfavorable looking country for mines that I have ever seen, but as the mines are here, what are the rock sharps going to do about it?

P-388 THE BONANZA TRAIL

This last remark may refer to the letter that the Smithsonian Institute in Washington sent to Enos A. Wall in 1876. They courteously acknowledged the piece of petrified Wood "shot through" with horn silver, which he had sent them. and described the sample as an "interesting fake as silver in nature is not formed in petrified wood." Barbee continued to write letters to the Tribune and brought thousands of miners into the district, attracted by such statements as:

Our mines are our capital; our banks are sand banks. We draw on them at will and our drafts are never dishonored.

This sandstone country beats all the boys, and it is amusing to see how excited they get when they go round to see the sheets of silver which are exposed all over the different reefs . . . This is the most unfavorable looking country for mines that I have ever seen, but as the mines are here, what are the rock sharps going to do about it?

P-388 THE BONANZA TRAIL

This last remark may refer to the letter that the Smithsonian Institute in Washington sent to Enos A. Wall in 1876. They courteously acknowledged the piece of petrified Wood "shot through" with horn silver, which he had sent them. and described the sample as an "interesting fake as silver in nature is not formed in petrified wood." Barbee continued to write letters to the Tribune and brought thousands of miners into the district, attracted by such statements as:

Our mines are our capital; our banks are sand banks. We draw on them at will and our drafts are never dishonored.

On reading the above, I contacted Leslie Hale who quickly responded by tracking down 16 Silver Reef specimens that had been sent to the Smithsonian and photographed them with her phone to get them to me quickly.

Hi Dave,

I’ve completed my research on the specimens, and yesterday I journeyed out to the storage facility and took quick photos on my phone, just so you can see what the specimens look like. My department has recently lost the volunteer who has been taking our publication quality photographs for the past 7 years. I’m no longer certain what the procedure is to have objects added to the project list for the building photographers, but I suspect it will take quite a while (especially because of the shutdown), and I didn’t want you to have to wait that long to see what the specimens look like.

None of them are related in any way to the correspondence you read about in “The Bonanza Trail” between the Smithsonian Institution and Enos A. Wall, and I could not find any record of that in the National Museum of Natural History correspondence files or the Smithsonian Institution Archives. Apparently, the documentation of identification and assay requests at that time were not kept for posterity, and the rock would have been returned to the requestor, not added to the museum collection as a specimen.

I’m going to have to send you multiple messages, as my server will not allow me to send emails out with more than three photo attachments.

NMNH#14730: This specimen was a purchase, from John Kemble. The price was $27, and it was most likely bought in 1881. That’s all I can find out about this one, the records from that long ago are a bit spotty.

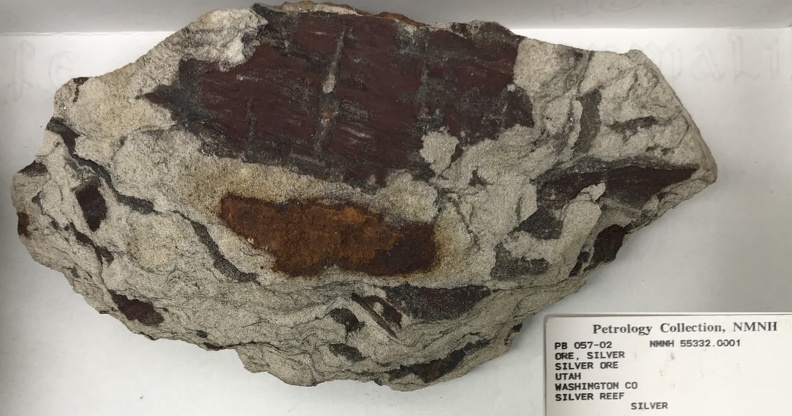

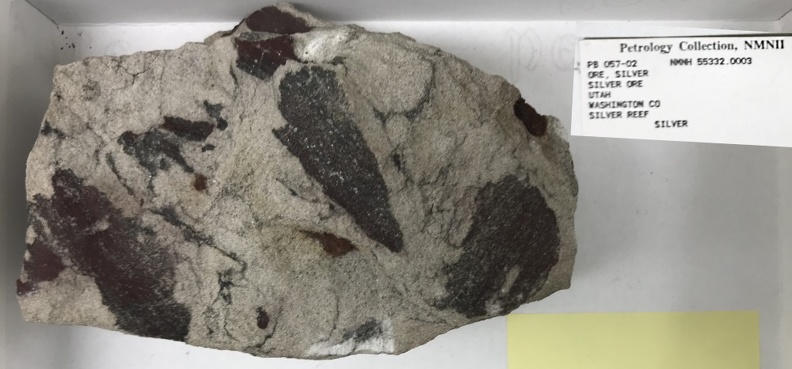

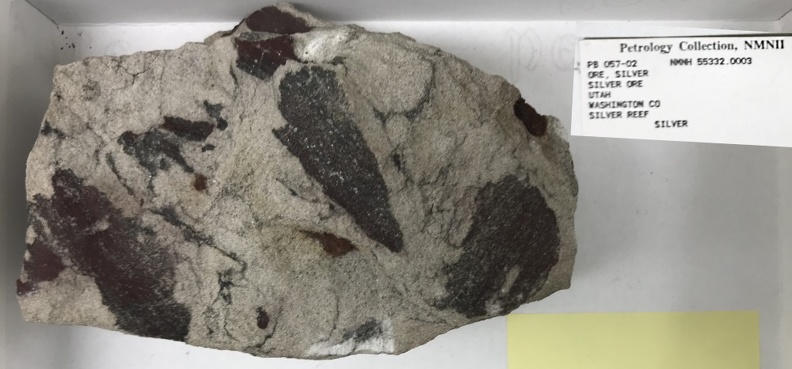

NMNH#55322, 55326, 55328, 55329-1, 55329-2, 55331, 55332-1, 55332-2, 55332-3, and 55333: This suite of ten specimens was part of a larger donation from Professor J.E. Clayton in 1884. The accession number of this gift is 15130, and at the time the specimens were described as “Silver Sandstone”.

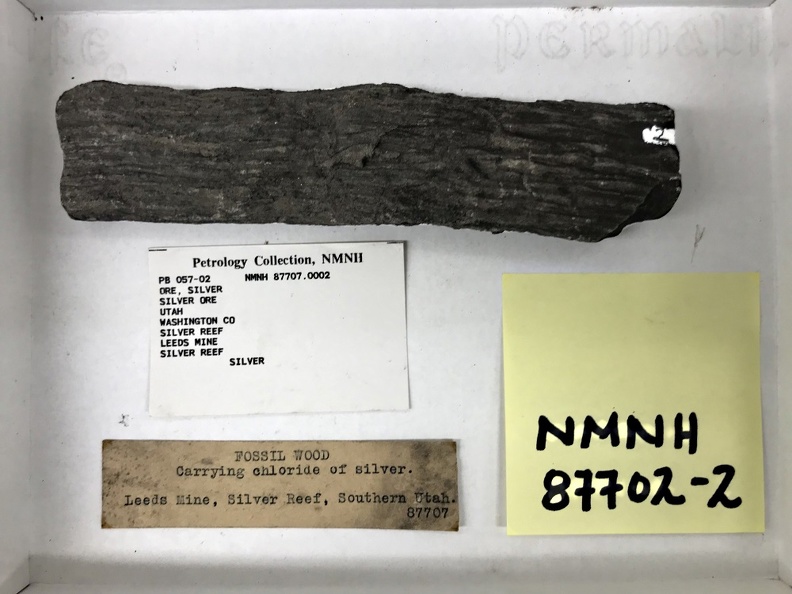

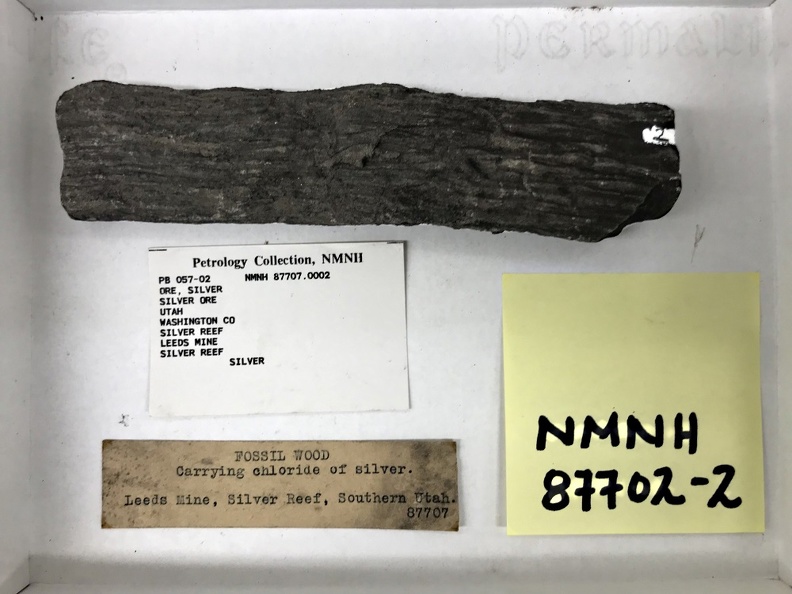

NMNH#87707-1 and 87707-2: These two specimens of fossil wood were a gift from Gardner F. Williams on April 15, 1912 and the accession number of the donation is 53898.

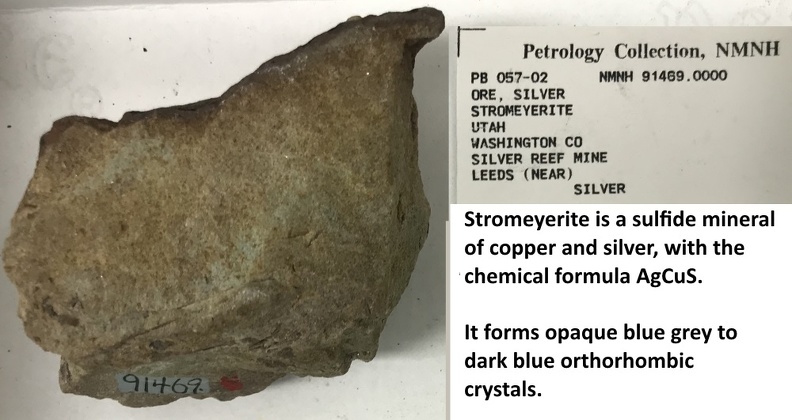

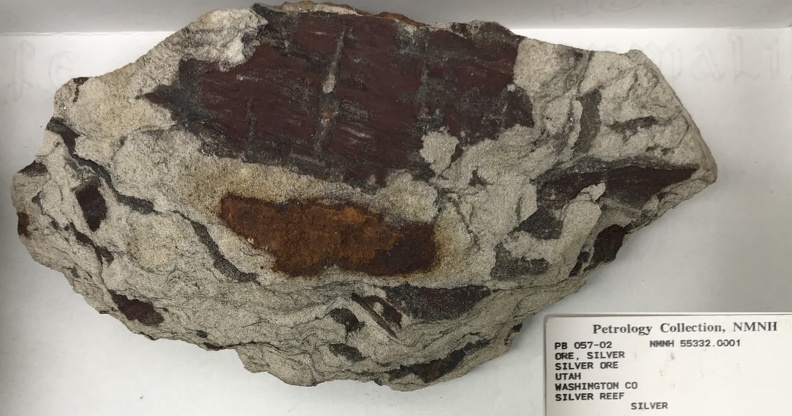

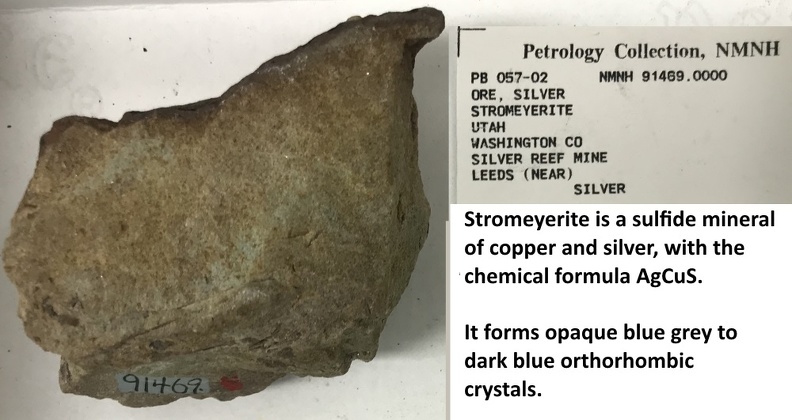

NMNH#91468 and 91469: These two specimens were “collected for the museum” by one of our own curators (a Smithsonian employee, in other words), William F. Foshag. They were catalogued into the National Collection on June 26, 1922 under accession 68480.

I don’t have an image for 109285-9997, but it was quite small and not fossil-bearing. I don’t think you’d get much out of a photograph from my phone of that particular specimen.

Momentarily I’ll be sending you the additional photos, no more than three per message. Please let me know which specimens you require photos of, and in the meantime I’ll continue to investigate what avenues are available to me at this time for obtaining publication-quality images of these specimens.

Sincerely, Leslie Hale

National Rock and Ore Collection Manager

Department of Mineral Sciences

I’ve completed my research on the specimens, and yesterday I journeyed out to the storage facility and took quick photos on my phone, just so you can see what the specimens look like. My department has recently lost the volunteer who has been taking our publication quality photographs for the past 7 years. I’m no longer certain what the procedure is to have objects added to the project list for the building photographers, but I suspect it will take quite a while (especially because of the shutdown), and I didn’t want you to have to wait that long to see what the specimens look like.

None of them are related in any way to the correspondence you read about in “The Bonanza Trail” between the Smithsonian Institution and Enos A. Wall, and I could not find any record of that in the National Museum of Natural History correspondence files or the Smithsonian Institution Archives. Apparently, the documentation of identification and assay requests at that time were not kept for posterity, and the rock would have been returned to the requestor, not added to the museum collection as a specimen.

I’m going to have to send you multiple messages, as my server will not allow me to send emails out with more than three photo attachments.

NMNH#14730: This specimen was a purchase, from John Kemble. The price was $27, and it was most likely bought in 1881. That’s all I can find out about this one, the records from that long ago are a bit spotty.

NMNH#55322, 55326, 55328, 55329-1, 55329-2, 55331, 55332-1, 55332-2, 55332-3, and 55333: This suite of ten specimens was part of a larger donation from Professor J.E. Clayton in 1884. The accession number of this gift is 15130, and at the time the specimens were described as “Silver Sandstone”.

NMNH#87707-1 and 87707-2: These two specimens of fossil wood were a gift from Gardner F. Williams on April 15, 1912 and the accession number of the donation is 53898.

NMNH#91468 and 91469: These two specimens were “collected for the museum” by one of our own curators (a Smithsonian employee, in other words), William F. Foshag. They were catalogued into the National Collection on June 26, 1922 under accession 68480.

I don’t have an image for 109285-9997, but it was quite small and not fossil-bearing. I don’t think you’d get much out of a photograph from my phone of that particular specimen.

Momentarily I’ll be sending you the additional photos, no more than three per message. Please let me know which specimens you require photos of, and in the meantime I’ll continue to investigate what avenues are available to me at this time for obtaining publication-quality images of these specimens.

Sincerely, Leslie Hale

National Rock and Ore Collection Manager

Department of Mineral Sciences

Thank you Leslie!

The first image is of a specimen purchased from John Kemble himself.

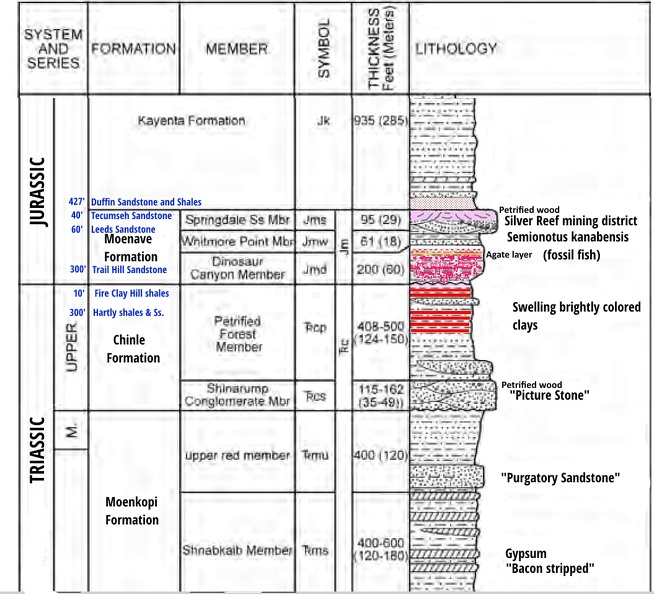

Others reveal the layer after layer of vegetative debris that was laid down as the 60 foot thick Leeds Sandstone was being formed.

A silver chloride petrified limb section.

A piece of petrified wood showing a bit of copper - usually found in the southern part of the area.

Who would suspect this rock as being special?

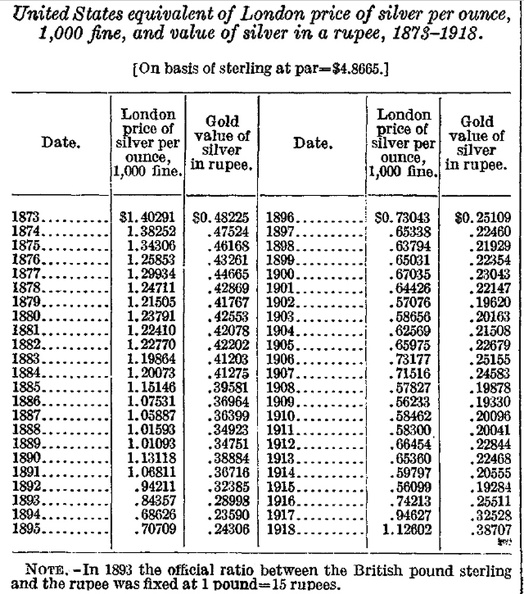

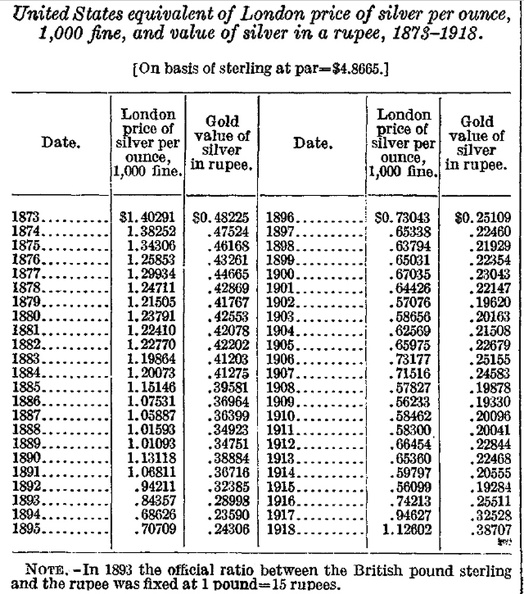

The Silver Reef mining area began dying in 1881 as the richest ores became more difficult to reach and the price of silver continued to fall.

All of the silver has been found west of the Hurricane Fault. The sandstone layer full of petrified wood continues on to the east of the fault but little if any silver has ever been found there.

Now the question becomes: "Where did the silver come from"?

You're down here in the bilges with the wharf rats. You will get more mileage above on the upper decks.

You're down here in the bilges with the wharf rats. You will get more mileage above on the upper decks.