Post by 1dave on Apr 28, 2019 9:32:20 GMT -5

Worth Downloading!

imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/educators/elements/imagine/Cosmic.pdf

2. Large Stars

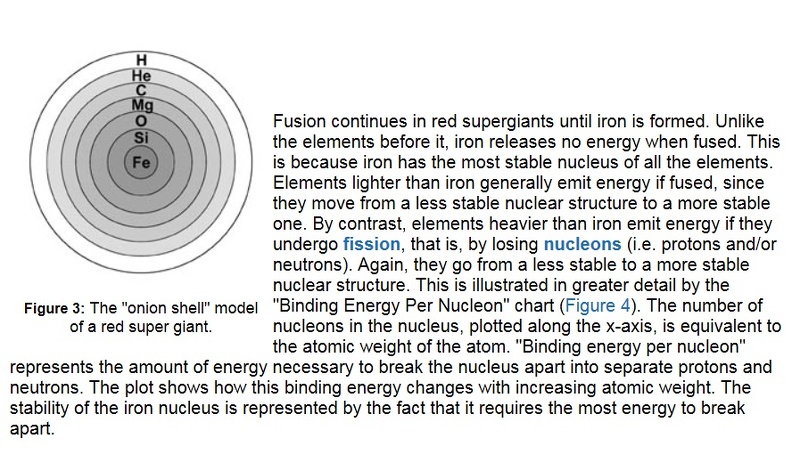

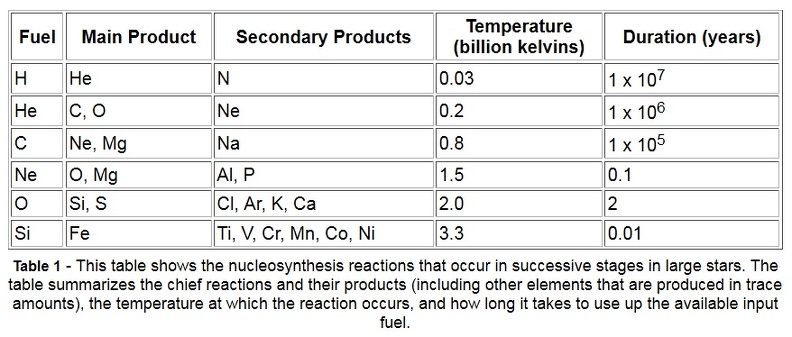

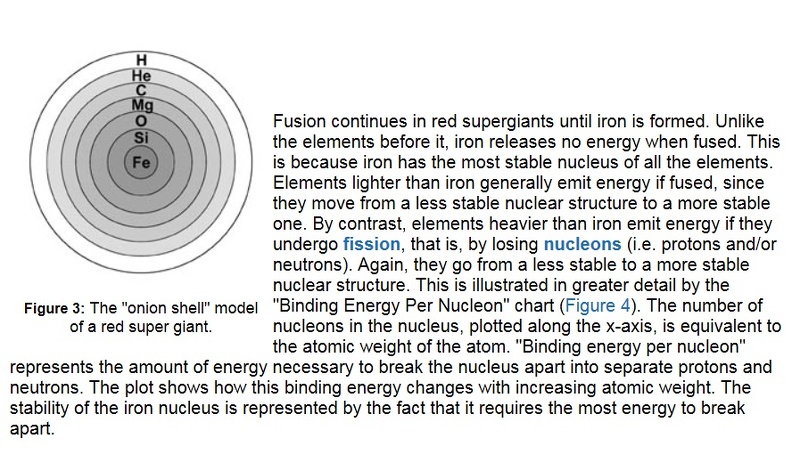

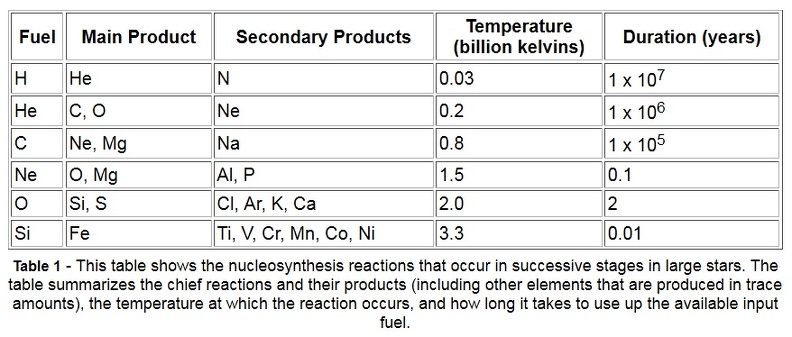

Stars larger than 8 times the mass of our Sun begin their lives the same way smaller stars do: by fusing hydrogen into helium. However, a large star burns hotter and faster, fusing all the hydrogen in its core to helium in less than 1 billion years. The star then becomes a red supergiant, similar to a red giant, only larger. Unlike red giants, these red supergiants have enough mass to create greater gravitational pressure, and therefore higher core temperatures. They fuse helium into carbon, carbon and helium into oxygen, and two carbon atoms into magnesium. Through a combination of such processes, successively heavier elements, up to iron, are formed (see Table 1). Each successive process requires a higher temperature (up to 3.3 billion kelvins) and lasts for a shorter amount of time (as short as a few days). The structure of a red supergiant becomes like an onion (see Figure 3), with different elements being fused at different temperatures in layers around the core. Convection brings the elements near the star’s surface, where the strong stellar winds disperse them into space.

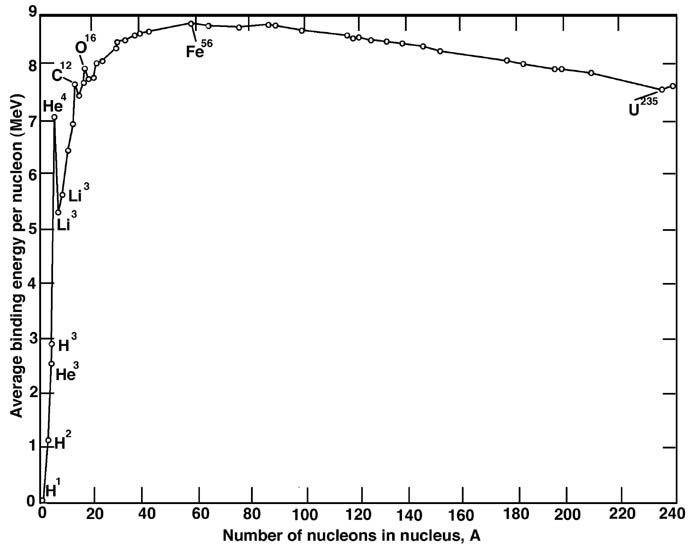

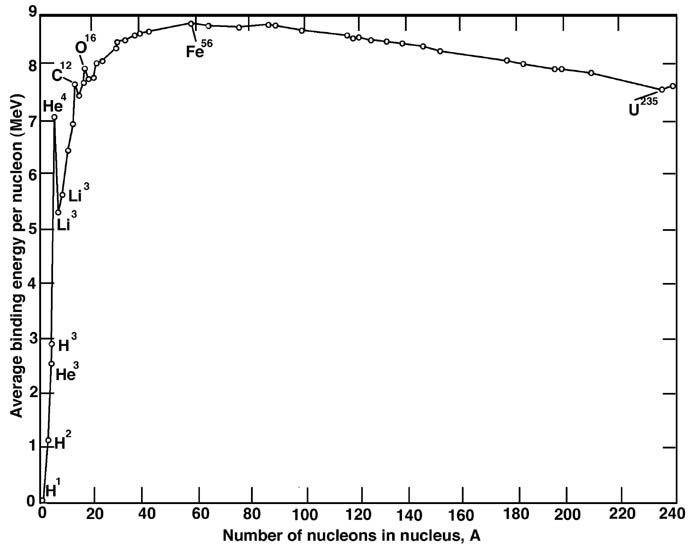

This is illustrated in greater detail by the “Binding Energy Per Nucleon” chart (Figure 4). The number of nucleons in the nucleus, plotted along the x-axis, is equivalent to the atomic weight of the atom. “Binding energy per nucleon” represents the amount of energy necessary to break the nucleus apart into separate protons and neutrons. The plot shows how this binding energy changes with increasing atomic weight. The stability of the iron nucleus is represented by the fact that it requires the most energy to break apart. Another reason fusion does not go beyond iron is that the temperatures necessary become so high that the nuclei “melt” before they can fuse. That is, the thermal energy due to the high temperature breaks silicon nuclei into separate helium nuclei. These helium nuclei then combine with elements such as chlorine, argon, potassium, and calcium to make elements from titanium through iron. Large stars also produce elements heavier than iron via neutron capture. Because of higher temperatures in large stars, the neutrons are supplied from the interaction of helium with neon. This neutron capture process takes place over thousands of years. The abundances of selected Figure 3: The “onion shell” model of a red super giant. 7 [/div]Figure 4: The average binding energy per nucleon as a function of number of nucleons in the atomic nucleus. Energy is released when nuclei with smaller binding energies combine or split to form nuclei with larger binding energies. This happens via fusion for elements below iron, and via fission for elements above iron. elements from iron to zirconium can be attributed to this type of production in large stars. Again, convection and stellar winds help disperse these elements.

imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/educators/elements/imagine/Cosmic.pdf

I. Introduction: Our Cosmic Connection to the Elements

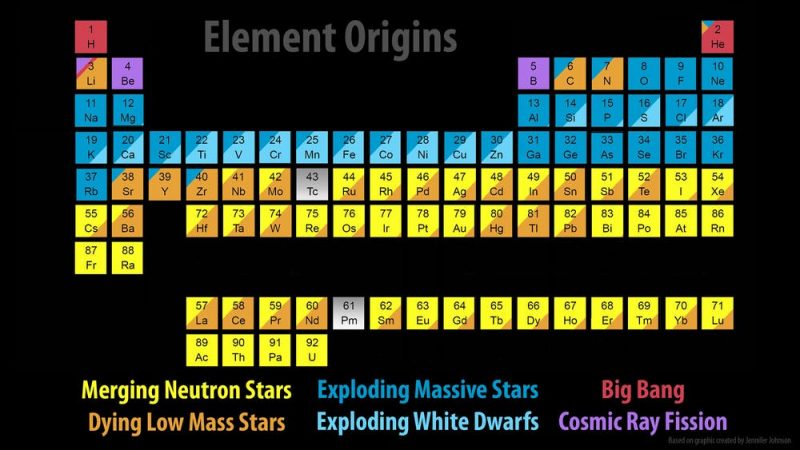

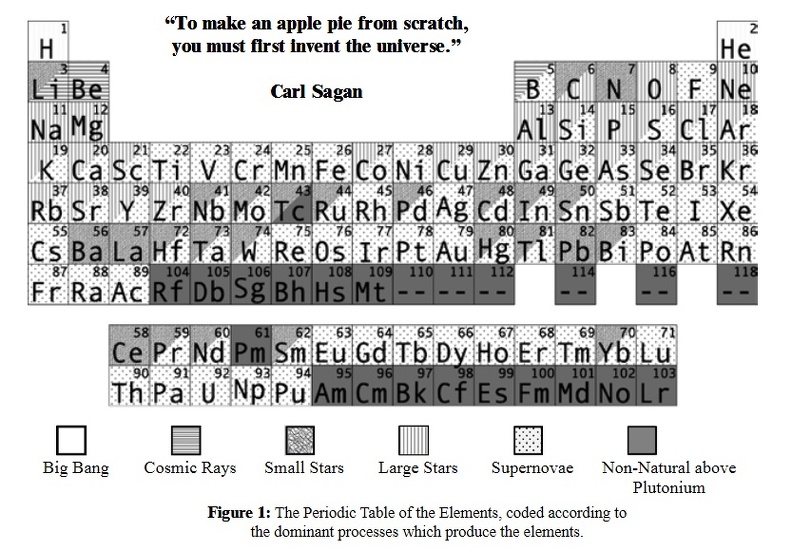

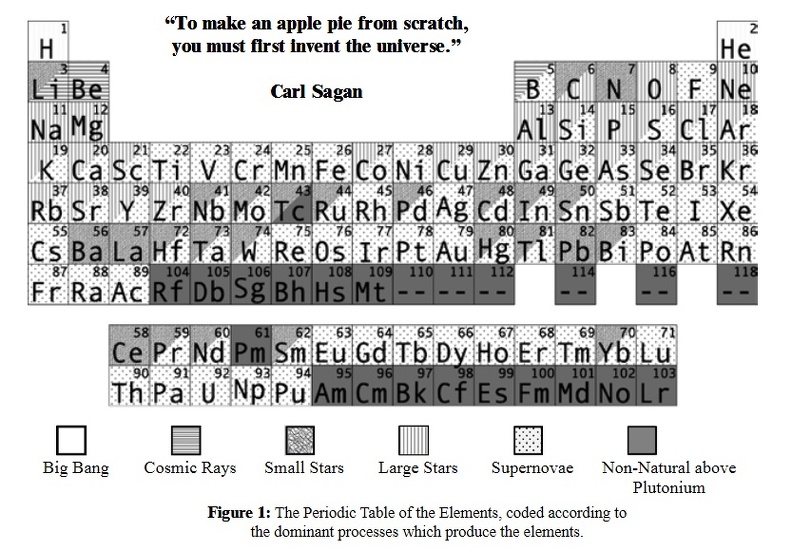

The chemical elements are all around us, and are part of us. The composition of the Earth, and the chemistry that governs the Earth and its biology are rooted in these elements. The elements have their ultimate origins in cosmic events. Further, different elements come from a variety of different events. So the elements that make up life itself reflect a variety of events that take place in the Universe.

The hydrogen found in water and hydrocarbons was formed in the moments after the Big Bang. Carbon, the basis for all terrestrial life, was formed in small stars.

Elements of lower abundance in living organisms but essential to our biology, such as calcium and iron, were formed in large stars.

Heavier elements important to our environment, such as gold, were formed in the explosive power of supernovae. And light elements used in our technology were formed via cosmic rays.

The solar nebula, from which our solar system was formed, was seeded with these elements, and they were present at the Earth’s formation. Our very existence is connected to these elements, and to their cosmic origin.

The chemical elements are all around us, and are part of us. The composition of the Earth, and the chemistry that governs the Earth and its biology are rooted in these elements. The elements have their ultimate origins in cosmic events. Further, different elements come from a variety of different events. So the elements that make up life itself reflect a variety of events that take place in the Universe.

The hydrogen found in water and hydrocarbons was formed in the moments after the Big Bang. Carbon, the basis for all terrestrial life, was formed in small stars.

Elements of lower abundance in living organisms but essential to our biology, such as calcium and iron, were formed in large stars.

Heavier elements important to our environment, such as gold, were formed in the explosive power of supernovae. And light elements used in our technology were formed via cosmic rays.

The solar nebula, from which our solar system was formed, was seeded with these elements, and they were present at the Earth’s formation. Our very existence is connected to these elements, and to their cosmic origin.

1. Small Stars

Stars less than about eight times the mass of our Sun are considered medium and small size stars. The production of elements in stars in this range is similar, and these stars share a similar fate. They begin by fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores. This process continues for billions of years, until there is no longer enough hydrogen in the star’s core to fuse more helium. Without the energy from fusion, there is nothing to counteract the force of gravity, and the star begins to collapse inward. This causes an increase in temperature and pressure. Due to this collapse, the hydrogen in the star’s middle layers becomes hot enough to fuse. The hydrogen begins to fuse into helium in a “shell” around the star’s core. The heat from this reaction “puffs up” the star’s outer layers, making the star expand far beyond its previous size. This expansion cools the outer layers, turning them red. At this point the star is a red giant.

The star’s core continues to collapse, until the pressure causes the core temperature to reach 100 million Kelvin. This is hot enough for the helium in the core to fuse into carbon. Energy from this reaction sustains the star, keeping it from further collapse. Nitrogen is fused in a similar way. After a much shorter period of time, there is no more material to fuse in the core. The star is left with carbon in its core, but the temperature is not hot enough to fuse carbon. However, if the star has a mass between 2 and 8 times the mass of the sun, fusion of helium can take place in a shell of gas surrounding the core. In addition, fusion of hydrogen takes place in a shell on top of this. The star is then known as an Asymptotic Giant.

Motion of the gas between these shells and the core dredges up carbon from the core. The helium shell is also replenished as the result of fusion in the hydrogen shell. This occasionally leads to explosive fusion in the helium shell. During these events, the outermost layers of the star are blown off, and a strong stellar wind develops. This ultimately leads to the formation of a planetary nebula. The nebula may contain up to 10% of the star’s mass. Both the nebula and the wind disperse into space some of the elements created by the star.

While the star is an Asymptotic Giant, heavier elements can form in the helium burning shell. They are produced by a process called neutron capture. Neutron capture occurs when a free neutron collides with an atomic nucleus and sticks. If this makes the nucleus unstable, the neutron will decay into a proton and an electron, thus producing a different element with a new atomic number.

In the helium fusion layer of Asymptotic Giants, this process takes place over thousands of years. The interaction of the helium with the carbon in this layer releases neutrons at just the right rate. These neutrons interact with heavy elements that have been present in the star since its birth. So over time, a single iron 26Fe56 nucleus might capture one of these neutrons, becoming Fe57. A thousand years later, it might capture another. If the iron nucleus captures enough26 neutrons to become 26Fe59, it would be unstable. One neutron would then decay into a proton and an electron, creating an atom of 27Co59, which is higher than iron on the periodic table. During this Asymptotic Giant phase, conditions are right for small stars to contribute in this way to the abundance of selected elements from niobium to bismuth.

After the Asymptotic Giant phase, the outer shell of the star is blown off and the star becomes white dwarf. A white dwarf is a very small, hot star, with a density so high that a teaspoon of its material would weigh a ton on Earth! If the white dwarf star is part of a binary star system (two stars orbiting around each other), gas from its companion star may be “pulled off” and fall onto the white dwarf. If matter accumulates rapidly on the white dwarf, the high temperature and intense gravity of the white dwarf cause the new gas to fuse in a sudden explosion called a nova. A nova explosion may temporarily make the white dwarf appear up to 10,000 times brighter. The fusion in a nova also creates new elements, dispersing more helium, carbon, oxygen, some nitrogen, and neon.

In rare cases, the white dwarf itself can detonate in a massive explosion which astronomers call a Type Ia supernova. This occurs if a white dwarf is part of a binary star system, and matter accumulates slowly onto the white dwarf. If enough matter accumulates, then the white dwarf cannot support the added weight, and begins to collapse. This collapse heats the helium and carbon in the white dwarf, which rapidly fuse into nickel, cobalt and iron. This burning occurs so fast that the white dwarf detonates, dispersing all the elements created during the star’s lifetime, and leaving nothing behind. This is a rare occurrence in which all the elements created in a small star are scattered into space.

Stars less than about eight times the mass of our Sun are considered medium and small size stars. The production of elements in stars in this range is similar, and these stars share a similar fate. They begin by fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores. This process continues for billions of years, until there is no longer enough hydrogen in the star’s core to fuse more helium. Without the energy from fusion, there is nothing to counteract the force of gravity, and the star begins to collapse inward. This causes an increase in temperature and pressure. Due to this collapse, the hydrogen in the star’s middle layers becomes hot enough to fuse. The hydrogen begins to fuse into helium in a “shell” around the star’s core. The heat from this reaction “puffs up” the star’s outer layers, making the star expand far beyond its previous size. This expansion cools the outer layers, turning them red. At this point the star is a red giant.

The star’s core continues to collapse, until the pressure causes the core temperature to reach 100 million Kelvin. This is hot enough for the helium in the core to fuse into carbon. Energy from this reaction sustains the star, keeping it from further collapse. Nitrogen is fused in a similar way. After a much shorter period of time, there is no more material to fuse in the core. The star is left with carbon in its core, but the temperature is not hot enough to fuse carbon. However, if the star has a mass between 2 and 8 times the mass of the sun, fusion of helium can take place in a shell of gas surrounding the core. In addition, fusion of hydrogen takes place in a shell on top of this. The star is then known as an Asymptotic Giant.

Motion of the gas between these shells and the core dredges up carbon from the core. The helium shell is also replenished as the result of fusion in the hydrogen shell. This occasionally leads to explosive fusion in the helium shell. During these events, the outermost layers of the star are blown off, and a strong stellar wind develops. This ultimately leads to the formation of a planetary nebula. The nebula may contain up to 10% of the star’s mass. Both the nebula and the wind disperse into space some of the elements created by the star.

While the star is an Asymptotic Giant, heavier elements can form in the helium burning shell. They are produced by a process called neutron capture. Neutron capture occurs when a free neutron collides with an atomic nucleus and sticks. If this makes the nucleus unstable, the neutron will decay into a proton and an electron, thus producing a different element with a new atomic number.

In the helium fusion layer of Asymptotic Giants, this process takes place over thousands of years. The interaction of the helium with the carbon in this layer releases neutrons at just the right rate. These neutrons interact with heavy elements that have been present in the star since its birth. So over time, a single iron 26Fe56 nucleus might capture one of these neutrons, becoming Fe57. A thousand years later, it might capture another. If the iron nucleus captures enough26 neutrons to become 26Fe59, it would be unstable. One neutron would then decay into a proton and an electron, creating an atom of 27Co59, which is higher than iron on the periodic table. During this Asymptotic Giant phase, conditions are right for small stars to contribute in this way to the abundance of selected elements from niobium to bismuth.

After the Asymptotic Giant phase, the outer shell of the star is blown off and the star becomes white dwarf. A white dwarf is a very small, hot star, with a density so high that a teaspoon of its material would weigh a ton on Earth! If the white dwarf star is part of a binary star system (two stars orbiting around each other), gas from its companion star may be “pulled off” and fall onto the white dwarf. If matter accumulates rapidly on the white dwarf, the high temperature and intense gravity of the white dwarf cause the new gas to fuse in a sudden explosion called a nova. A nova explosion may temporarily make the white dwarf appear up to 10,000 times brighter. The fusion in a nova also creates new elements, dispersing more helium, carbon, oxygen, some nitrogen, and neon.

In rare cases, the white dwarf itself can detonate in a massive explosion which astronomers call a Type Ia supernova. This occurs if a white dwarf is part of a binary star system, and matter accumulates slowly onto the white dwarf. If enough matter accumulates, then the white dwarf cannot support the added weight, and begins to collapse. This collapse heats the helium and carbon in the white dwarf, which rapidly fuse into nickel, cobalt and iron. This burning occurs so fast that the white dwarf detonates, dispersing all the elements created during the star’s lifetime, and leaving nothing behind. This is a rare occurrence in which all the elements created in a small star are scattered into space.

2. Large Stars

Stars larger than 8 times the mass of our Sun begin their lives the same way smaller stars do: by fusing hydrogen into helium. However, a large star burns hotter and faster, fusing all the hydrogen in its core to helium in less than 1 billion years. The star then becomes a red supergiant, similar to a red giant, only larger. Unlike red giants, these red supergiants have enough mass to create greater gravitational pressure, and therefore higher core temperatures. They fuse helium into carbon, carbon and helium into oxygen, and two carbon atoms into magnesium. Through a combination of such processes, successively heavier elements, up to iron, are formed (see Table 1). Each successive process requires a higher temperature (up to 3.3 billion kelvins) and lasts for a shorter amount of time (as short as a few days). The structure of a red supergiant becomes like an onion (see Figure 3), with different elements being fused at different temperatures in layers around the core. Convection brings the elements near the star’s surface, where the strong stellar winds disperse them into space.

Fusion continues in red supergiants until iron is formed. Unlike the elements before it, iron releases no energy when fused. This is because iron has the most stable nucleus of all the elements. Elements lighter than iron generally emit energy if fused, since they move from a less stable nuclear structure to a more stable one. By contrast, elements heavier than iron emit energy if they undergo fission, that is, by losing nucleons (i.e.protons and/or neutrons). Again, they go from a less stable to a more stable nuclear structure.

This is illustrated in greater detail by the “Binding Energy Per Nucleon” chart (Figure 4). The number of nucleons in the nucleus, plotted along the x-axis, is equivalent to the atomic weight of the atom. “Binding energy per nucleon” represents the amount of energy necessary to break the nucleus apart into separate protons and neutrons. The plot shows how this binding energy changes with increasing atomic weight. The stability of the iron nucleus is represented by the fact that it requires the most energy to break apart. Another reason fusion does not go beyond iron is that the temperatures necessary become so high that the nuclei “melt” before they can fuse. That is, the thermal energy due to the high temperature breaks silicon nuclei into separate helium nuclei. These helium nuclei then combine with elements such as chlorine, argon, potassium, and calcium to make elements from titanium through iron. Large stars also produce elements heavier than iron via neutron capture. Because of higher temperatures in large stars, the neutrons are supplied from the interaction of helium with neon. This neutron capture process takes place over thousands of years. The abundances of selected Figure 3: The “onion shell” model of a red super giant. 7 [/div]Figure 4: The average binding energy per nucleon as a function of number of nucleons in the atomic nucleus. Energy is released when nuclei with smaller binding energies combine or split to form nuclei with larger binding energies. This happens via fusion for elements below iron, and via fission for elements above iron. elements from iron to zirconium can be attributed to this type of production in large stars. Again, convection and stellar winds help disperse these elements.