Post by 1dave on Nov 5, 2021 6:54:23 GMT -5

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernova_impostor

Supernova impostors are stellar explosions that appear at first to be a supernova but do not destroy their progenitor stars. As such, they are a class of extra-powerful novae. They are also known as Type V supernovae, Eta Carinae analogs, and giant eruptions of luminous blue variables (LBV).[2]

Contents

1 Appearance, origin and mass loss

2 Examples

3 See also

4 References

Appearance, origin and mass loss

Supernova impostors appear as remarkably faint supernovae of spectral type IIn—which have hydrogen in their spectrum and narrow spectral lines that indicate relatively low gas speeds. These impostors exceed their pre-outburst states by several magnitudes, with typical peak absolute visual magnitudes of −11 to −14, making these outbursts as bright as the most luminous stars. The trigger mechanism of these outbursts remains unexplained, though it is thought to be caused by violating the classical Eddington luminosity limit, initiating severe mass loss. If the ratio of radiated energy to kinetic energy is near unity, as in Eta Carinae, then we might expect an ejected mass of about 0.16 solar masses.

Examples

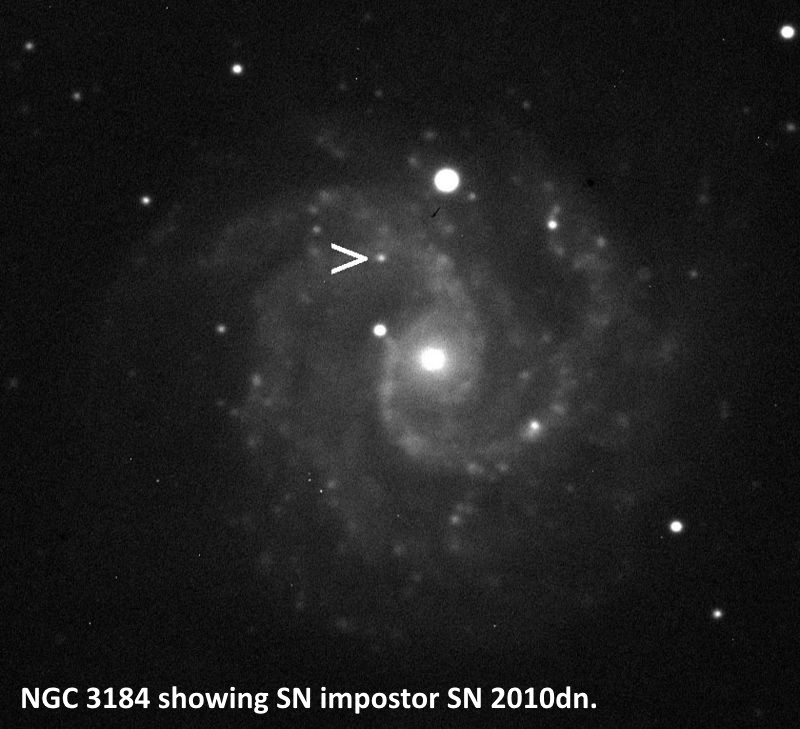

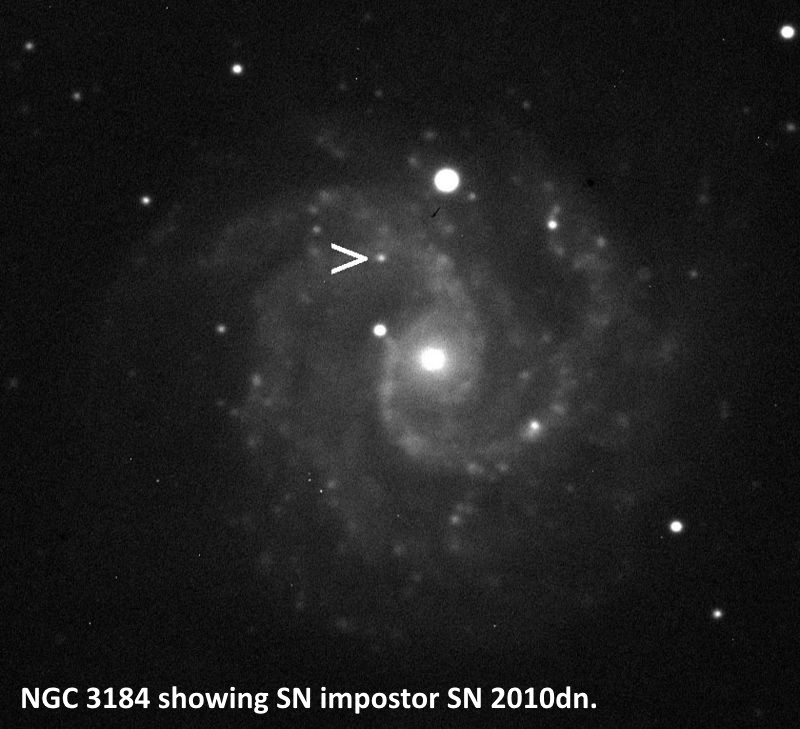

Possible examples of supernova impostors include the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae, P Cygni, SN 1961V,[3] SN 1954J, SN 1997bs, SN 2008S in NGC 6946, and SN 2010dn[1] where detections of the surviving progenitor stars are claimed.

One supernova impostor that made news after the fact was the one observed on October 20, 2004, in the galaxy UGC 4904 by Japanese amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki. This LBV star exploded just two years later, on October 11, 2006, as supernova SN 2006jc.[4]

See also

Failed supernova

References

Smith, Nathan; Weidong, Li; Silverman, Jeffrey; Ganeshalingam, Mo; Filippenko, Alexei (2011). "Luminous Blue Variable eruptions and related transients: Diversity of progenitors and outburst properties". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 415: 773–810. arXiv:1010.3718. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415..773S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18763.x.

Smith, Nathan; Ganeshalingam, Mohan; Chornock, Ryan; Filippenko, Alexei; Weidong, Li; et al. (2009). "SN 2008S: A Cool Super-Eddington Wind in a Supernova Impostor". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 697 (1): L49–L53. arXiv:0811.3929. Bibcode:2009ApJ...697L..49S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/L49.

Kochanek, C.S.; Szczygiel, D.M.; Stanek, K.Z. (2010). "The Supernova Impostor Impostor SN 1961V: Spitzer Shows That Zwicky Was Right (Again)". The Astrophysical Journal. 737: 76. arXiv:1010.3704. Bibcode:2011ApJ...737...76K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/737/2/76.

"NASA – Supernova Imposter Goes Supernova". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/news/topstory/2007/supernova_imposter.html

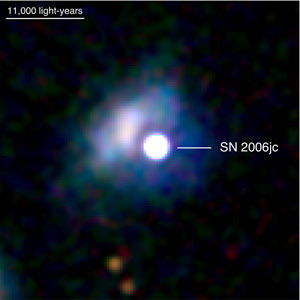

In a galaxy far, far away, a massive star suffered a nasty double whammy. On Oct. 20, 2004, Japanese amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki saw the star let loose an outburst so bright that it was initially mistaken for a supernova. The star survived, but for only two years. On Oct. 11, 2006, professional and amateur astronomers witnessed the star actually blowing itself to smithereens as Supernova 2006jc.

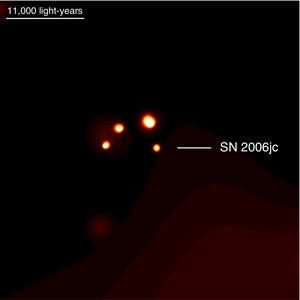

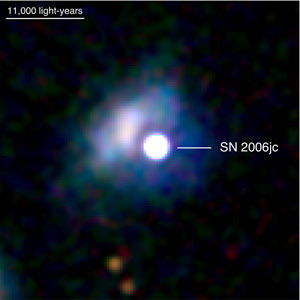

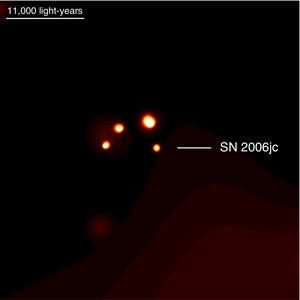

Swift Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope image of supernova 2006jc in the galaxy Image above: Swift Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope image of Supernova 2006jc in the galaxy UGC 4904 in three filters. Credit: NASA/Swift/S. Immler

"We have never observed a stellar outburst and then later seen the star explode," says University of California at Berkeley astronomer Ryan Foley. His group studied the event with ground-based telescopes, including the 10-meter (32.8-foot) Keck telescope in Hawaii. Narrow helium spectral lines showed that the supernova’s blast wave ran into a slow-moving shell of material, presumably the progenitor’s upper layers ejected just two years earlier. If the spectral lines had been caused by the supernova’s fast-moving blast wave, the lines would have been much broader.

Another group, led by Stefan Immler of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., monitored SN 2006jc with NASA’s Swift satellite and Chandra X-ray Observatory. By observing how the supernova brightened in X-rays, a result of the blast wave slamming into the outburst ejecta, they could measure the amount of gas blown off in the 2004 outburst: about 0.01 solar mass.

"The beautiful aspect of SN 2006jc is that everything makes sense," says Immler. "Even though our two teams observed the supernova with different instruments and at different wavelengths, we have reached identical conclusions about what happened."

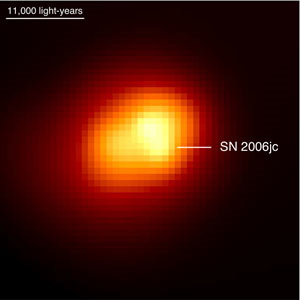

Swift X Image above: Swift X-ray Telescope image of Supernova 2006jc. Credit: NASA/Swift/S. Immler

"This event was a complete surprise," adds Alex Filippenko, leader of the University of California at Berkeley/Keck supernova group, and a coauthor on both studies. "It opens up a fascinating new window on how some kinds of stars die."

All the observations suggest that the supernova’s blast wave took only a few hours to reach the shell of material ejected two years earlier, which did not have time to drift very far from the star. As the wave smashed into the ejecta, it heated the gas to millions of degrees, hot enough to emit copious X-rays. NASA’s Swift satellite saw the supernova continue to brighten in X-rays for 100 days, something that has never been seen before in a supernova. All supernovae previously observed in X-rays have started off bright and then quickly faded to invisibility.

"You don’t need a lot of mass in the ejecta to produce a lot of X-rays," notes Immler. Swift’s ability to monitor the supernova’s X-ray rise and decline over six months was crucial to his team’s mass determination. But he adds that Chandra’s sharp resolution enabled his group to resolve the supernova from a bright X-ray source that appears in the field of view of Swift’s X-ray Telescope.

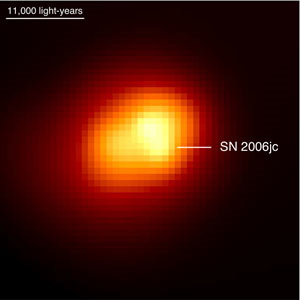

Chandra Observatory X Image above: Chandra X-ray Observatory image of Supernova 2006jc. Credit: NASA/CXC/S. Immler

"We could not have made this measurement without Chandra," says Immler, who is submitting his team’s paper to the Astrophysical Journal. "The synergy between Swift's fast response and its ability to observe a supernova every day for a long period, and Chandra's high spatial resolution, is leading to a lot of interesting results."

Foley and his colleagues, whose paper appears in the March 10 Astrophysical Journal Letters, propose that the star recently transitioned from a Luminous Blue Variable (LBV) star to a Wolf-Rayet star. An LBV is a massive star in a brief but unstable phase of stellar evolution. Similar to the 2004 eruption, LBVs are prone to blow off large amounts of mass in outbursts so extreme that they are frequently mistaken for supernovae, events dubbed "supernova impostors." Wolf-Rayet stars are hot, highly evolved stars that have shed their outer envelopes.

Most astronomers did not expect that a massive star would explode so soon after a major outburst, or that a Wolf-Rayet star would produce such a luminous eruption, so SN 2006jc represents a challenge for theorists. "It disrupts our current model of stellar evolution," says Foley. "We really don't know what caused this star to have such a large eruption so soon before it went supernova."

"SN 2006jc provides us with an important clue that LBV-style eruptions may be related to the deaths of massive stars, perhaps more closely than we used to think," adds coauthor Nathan Smith, also of the University of California at Berkeley. "The fact that we have no well-established theory for what actually causes these outbursts is the elephant in the living room that nobody is talking about."

SN 2006jc occurred in galaxy UGC 4904, located 77 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Lynx. The supernova explosion, a peculiar variant of a Type Ib, was first sighted by Itagaki, American amateur astronomer Tim Puckett, and Italian amateur Roberto Gorelli.

Related Links:

+ NASA Swift mission site

+ Chandra X-ray Observatory site

Robert Naeye

Goddard Space Flight Center

Supernova impostors are stellar explosions that appear at first to be a supernova but do not destroy their progenitor stars. As such, they are a class of extra-powerful novae. They are also known as Type V supernovae, Eta Carinae analogs, and giant eruptions of luminous blue variables (LBV).[2]

Contents

1 Appearance, origin and mass loss

2 Examples

3 See also

4 References

Appearance, origin and mass loss

Supernova impostors appear as remarkably faint supernovae of spectral type IIn—which have hydrogen in their spectrum and narrow spectral lines that indicate relatively low gas speeds. These impostors exceed their pre-outburst states by several magnitudes, with typical peak absolute visual magnitudes of −11 to −14, making these outbursts as bright as the most luminous stars. The trigger mechanism of these outbursts remains unexplained, though it is thought to be caused by violating the classical Eddington luminosity limit, initiating severe mass loss. If the ratio of radiated energy to kinetic energy is near unity, as in Eta Carinae, then we might expect an ejected mass of about 0.16 solar masses.

Examples

Possible examples of supernova impostors include the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae, P Cygni, SN 1961V,[3] SN 1954J, SN 1997bs, SN 2008S in NGC 6946, and SN 2010dn[1] where detections of the surviving progenitor stars are claimed.

One supernova impostor that made news after the fact was the one observed on October 20, 2004, in the galaxy UGC 4904 by Japanese amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki. This LBV star exploded just two years later, on October 11, 2006, as supernova SN 2006jc.[4]

See also

Failed supernova

References

Smith, Nathan; Weidong, Li; Silverman, Jeffrey; Ganeshalingam, Mo; Filippenko, Alexei (2011). "Luminous Blue Variable eruptions and related transients: Diversity of progenitors and outburst properties". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 415: 773–810. arXiv:1010.3718. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415..773S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18763.x.

Smith, Nathan; Ganeshalingam, Mohan; Chornock, Ryan; Filippenko, Alexei; Weidong, Li; et al. (2009). "SN 2008S: A Cool Super-Eddington Wind in a Supernova Impostor". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 697 (1): L49–L53. arXiv:0811.3929. Bibcode:2009ApJ...697L..49S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/L49.

Kochanek, C.S.; Szczygiel, D.M.; Stanek, K.Z. (2010). "The Supernova Impostor Impostor SN 1961V: Spitzer Shows That Zwicky Was Right (Again)". The Astrophysical Journal. 737: 76. arXiv:1010.3704. Bibcode:2011ApJ...737...76K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/737/2/76.

"NASA – Supernova Imposter Goes Supernova". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/news/topstory/2007/supernova_imposter.html

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain broken links or outdated information, and parts may not function in current web browsers. Visit NASA.gov for current information

Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain broken links or outdated information, and parts may not function in current web browsers. Visit NASA.gov for current information

In a galaxy far, far away, a massive star suffered a nasty double whammy. On Oct. 20, 2004, Japanese amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki saw the star let loose an outburst so bright that it was initially mistaken for a supernova. The star survived, but for only two years. On Oct. 11, 2006, professional and amateur astronomers witnessed the star actually blowing itself to smithereens as Supernova 2006jc.

Swift Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope image of supernova 2006jc in the galaxy Image above: Swift Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope image of Supernova 2006jc in the galaxy UGC 4904 in three filters. Credit: NASA/Swift/S. Immler

"We have never observed a stellar outburst and then later seen the star explode," says University of California at Berkeley astronomer Ryan Foley. His group studied the event with ground-based telescopes, including the 10-meter (32.8-foot) Keck telescope in Hawaii. Narrow helium spectral lines showed that the supernova’s blast wave ran into a slow-moving shell of material, presumably the progenitor’s upper layers ejected just two years earlier. If the spectral lines had been caused by the supernova’s fast-moving blast wave, the lines would have been much broader.

Another group, led by Stefan Immler of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., monitored SN 2006jc with NASA’s Swift satellite and Chandra X-ray Observatory. By observing how the supernova brightened in X-rays, a result of the blast wave slamming into the outburst ejecta, they could measure the amount of gas blown off in the 2004 outburst: about 0.01 solar mass.

"The beautiful aspect of SN 2006jc is that everything makes sense," says Immler. "Even though our two teams observed the supernova with different instruments and at different wavelengths, we have reached identical conclusions about what happened."

Swift X Image above: Swift X-ray Telescope image of Supernova 2006jc. Credit: NASA/Swift/S. Immler

"This event was a complete surprise," adds Alex Filippenko, leader of the University of California at Berkeley/Keck supernova group, and a coauthor on both studies. "It opens up a fascinating new window on how some kinds of stars die."

All the observations suggest that the supernova’s blast wave took only a few hours to reach the shell of material ejected two years earlier, which did not have time to drift very far from the star. As the wave smashed into the ejecta, it heated the gas to millions of degrees, hot enough to emit copious X-rays. NASA’s Swift satellite saw the supernova continue to brighten in X-rays for 100 days, something that has never been seen before in a supernova. All supernovae previously observed in X-rays have started off bright and then quickly faded to invisibility.

"You don’t need a lot of mass in the ejecta to produce a lot of X-rays," notes Immler. Swift’s ability to monitor the supernova’s X-ray rise and decline over six months was crucial to his team’s mass determination. But he adds that Chandra’s sharp resolution enabled his group to resolve the supernova from a bright X-ray source that appears in the field of view of Swift’s X-ray Telescope.

Chandra Observatory X Image above: Chandra X-ray Observatory image of Supernova 2006jc. Credit: NASA/CXC/S. Immler

"We could not have made this measurement without Chandra," says Immler, who is submitting his team’s paper to the Astrophysical Journal. "The synergy between Swift's fast response and its ability to observe a supernova every day for a long period, and Chandra's high spatial resolution, is leading to a lot of interesting results."

Foley and his colleagues, whose paper appears in the March 10 Astrophysical Journal Letters, propose that the star recently transitioned from a Luminous Blue Variable (LBV) star to a Wolf-Rayet star. An LBV is a massive star in a brief but unstable phase of stellar evolution. Similar to the 2004 eruption, LBVs are prone to blow off large amounts of mass in outbursts so extreme that they are frequently mistaken for supernovae, events dubbed "supernova impostors." Wolf-Rayet stars are hot, highly evolved stars that have shed their outer envelopes.

Most astronomers did not expect that a massive star would explode so soon after a major outburst, or that a Wolf-Rayet star would produce such a luminous eruption, so SN 2006jc represents a challenge for theorists. "It disrupts our current model of stellar evolution," says Foley. "We really don't know what caused this star to have such a large eruption so soon before it went supernova."

"SN 2006jc provides us with an important clue that LBV-style eruptions may be related to the deaths of massive stars, perhaps more closely than we used to think," adds coauthor Nathan Smith, also of the University of California at Berkeley. "The fact that we have no well-established theory for what actually causes these outbursts is the elephant in the living room that nobody is talking about."

SN 2006jc occurred in galaxy UGC 4904, located 77 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Lynx. The supernova explosion, a peculiar variant of a Type Ib, was first sighted by Itagaki, American amateur astronomer Tim Puckett, and Italian amateur Roberto Gorelli.

Related Links:

+ NASA Swift mission site

+ Chandra X-ray Observatory site

Robert Naeye

Goddard Space Flight Center