Post by 1dave on Mar 22, 2022 16:40:03 GMT -5

elementsunearthed.com/tag/thomas-range/

by David V. Black

by David V. Black

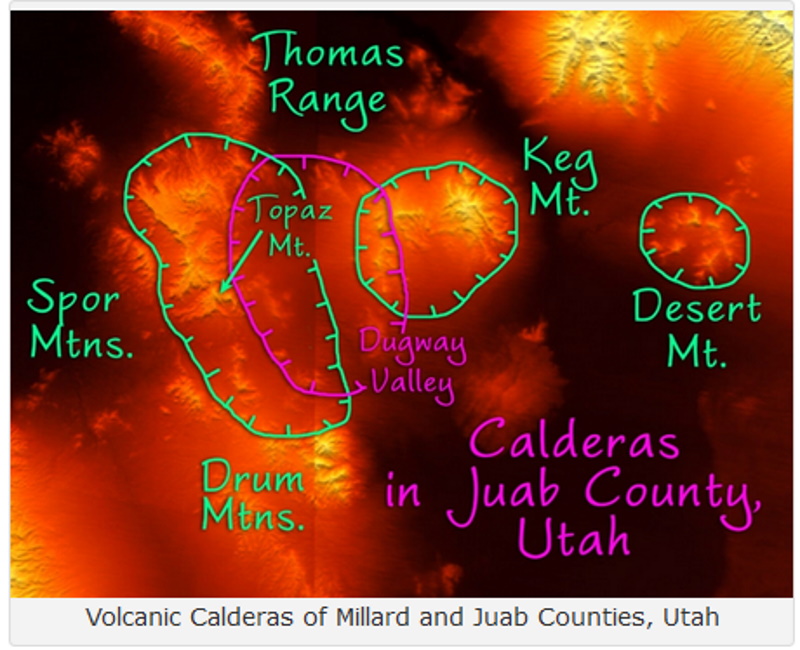

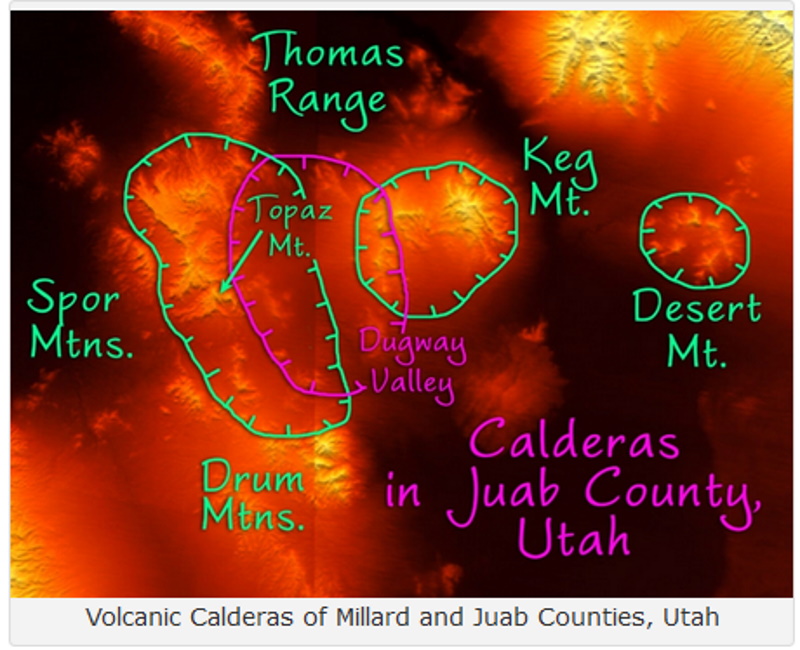

Most of the rocks in western Utah, where I’m from, were laid down as ocean deposits during the Paleozoic Era. Now all the layers of shale, limestone, and dolomite have been thrusted, twisted, and even overturned, so that in some areas the Paleozoic rocks lie on top of younger Mesozoic rocks. How could this have happened? But in addition to these sedimentary rocks, there are some anomalies; whole mountains that puzzled me because they didn’t fit in. My grandfather, who lived next door to us in our small hometown of Deseret, would take me for drives out on the west desert looking for trilobites or pine nuts or just collecting rocks. One area we visited was Topaz Mountain at the southern end of the Thomas Range in Juab County, where one can find topazes just by walking along an arroyo on a sunny day, following the flashes of light. The rocks there are weird, with strange cavities and a light gray texture much different than the surrounding mountains. I wondered where it came from, how the topazes got there, how old the rocks were, and above all, how geologists were able to answer these questions.

Desert Mt. Pass

View from Desert Mt. Pass

This was all very interesting to me as a child, but then geology got personal. My father was a farmer and cattle rancher, and one day in June of 1971, we were hauling a load of yearling heifers out to our ranch in southern Tooele County (about 50 miles due north of Deseret). As we were driving our old 1952 model half-ton truck over the pass on Desert Mt., the brakes and clutch both failed at the same time and we found ourselves rolling down the steep and winding road without any means of stopping (the road has since been improved, as you can see at right. Back then the road cut along the left side of the pass and was much more dangerous). Dad tried to slow the truck down by ramming it into the embankment on his side, but the impact jarred the cab, flung open the door on my side, and threw me from the cab (this truck had no seat belts). Fortunately, there is a gap in my memory at that point for several seconds. The next thing I can remember is lying on my back looking at the truck as it rolled away from me and disappeared out of sight over the edge of the embankment. Then I saw my right leg, which was twisted unnaturally, with my thigh badly torn up – a whole piece of my thigh seemed to be missing, as far as I could see through the tattered remains of my pants. The best I can figure is that the rear dual tires of the truck rolled over my leg, breaking it in two places and tearing up the skin and underlying tissue badly. Or my leg dragged over the rough, sharp rhyolite rocks of the mountain. Or both.

Desert Mt. Rhyolite

Rhyolite formations at Desert Mt. Pass

This was a hot day in June. We had water and snacks, but my father had sprained his ankle and could not walk. This was before cell phones or even CB radios, and we had no way of getting help. You have to visit the west desert of Utah to appreciate just how isolated it is. Dad lit the truck on fire, hoping the column of smoke would attract attention from the ranchers (including my grandfather) across Ereksen Valley, but no one saw it. Hours dragged by. I was slowly bleeding to death as blood seeped out of my wound, and I was going into shock. After about five desperate hours, my father saw a car sitting on the road leading up to the pass; they had stopped when they came around the corner and saw the smoldering remains of our cattle truck. Dad stood up and waved, and they drove on up. The car was driven by a an elderly couple from Odgen, Utah: rockhounds who were out on the west desert looking for Topaz Mt. All they had was a hand-drawn, inaccurate map and they were off course by 40 miles. Dad was able to ride in to the nearest phone (about 15 miles) and call the ambulance and Doc Lyman from Delta. After several days in Intensive Care, two months in the hospital with skin grafts, and another three months in body casts, I was finally able to walk again. I am lucky to have two legs.

So my life was profoundly affected by the geology of Utah’s west desert. Desert Mt. almost killed me; Topaz Mt. saved my life. So I have understandably been curious about the geology of these two mountains. I can honestly say that I am a part of that geology – somewhere on Desert Mt. there’s a small patch of dirt that used to be me. And that geology is a part of me, too – the doctors were never able to get all of the small rock fragments out of my leg that had been ground in. Yes, I know it’s a bit grotesque, but it’s literally true.

That’s why I’ve wanted to complete these episodes on the beryllium deposits of western Utah before doing any others, because telling that story includes the story of the geology of the area and how those two unusual mountains came to be there in the first place. The episodes are coming along nicely, and I have completed the geology section completely and offer it now for your enjoyment. The first episode (on the sources, uses, and geology of beryllium) will be ready in a few days; the second episode on the mining, refining, and hazards of beryllium will be ready by next week.

Desert Mt. Pass

View from Desert Mt. Pass

This was all very interesting to me as a child, but then geology got personal. My father was a farmer and cattle rancher, and one day in June of 1971, we were hauling a load of yearling heifers out to our ranch in southern Tooele County (about 50 miles due north of Deseret). As we were driving our old 1952 model half-ton truck over the pass on Desert Mt., the brakes and clutch both failed at the same time and we found ourselves rolling down the steep and winding road without any means of stopping (the road has since been improved, as you can see at right. Back then the road cut along the left side of the pass and was much more dangerous). Dad tried to slow the truck down by ramming it into the embankment on his side, but the impact jarred the cab, flung open the door on my side, and threw me from the cab (this truck had no seat belts). Fortunately, there is a gap in my memory at that point for several seconds. The next thing I can remember is lying on my back looking at the truck as it rolled away from me and disappeared out of sight over the edge of the embankment. Then I saw my right leg, which was twisted unnaturally, with my thigh badly torn up – a whole piece of my thigh seemed to be missing, as far as I could see through the tattered remains of my pants. The best I can figure is that the rear dual tires of the truck rolled over my leg, breaking it in two places and tearing up the skin and underlying tissue badly. Or my leg dragged over the rough, sharp rhyolite rocks of the mountain. Or both.

Desert Mt. Rhyolite

Rhyolite formations at Desert Mt. Pass

This was a hot day in June. We had water and snacks, but my father had sprained his ankle and could not walk. This was before cell phones or even CB radios, and we had no way of getting help. You have to visit the west desert of Utah to appreciate just how isolated it is. Dad lit the truck on fire, hoping the column of smoke would attract attention from the ranchers (including my grandfather) across Ereksen Valley, but no one saw it. Hours dragged by. I was slowly bleeding to death as blood seeped out of my wound, and I was going into shock. After about five desperate hours, my father saw a car sitting on the road leading up to the pass; they had stopped when they came around the corner and saw the smoldering remains of our cattle truck. Dad stood up and waved, and they drove on up. The car was driven by a an elderly couple from Odgen, Utah: rockhounds who were out on the west desert looking for Topaz Mt. All they had was a hand-drawn, inaccurate map and they were off course by 40 miles. Dad was able to ride in to the nearest phone (about 15 miles) and call the ambulance and Doc Lyman from Delta. After several days in Intensive Care, two months in the hospital with skin grafts, and another three months in body casts, I was finally able to walk again. I am lucky to have two legs.

So my life was profoundly affected by the geology of Utah’s west desert. Desert Mt. almost killed me; Topaz Mt. saved my life. So I have understandably been curious about the geology of these two mountains. I can honestly say that I am a part of that geology – somewhere on Desert Mt. there’s a small patch of dirt that used to be me. And that geology is a part of me, too – the doctors were never able to get all of the small rock fragments out of my leg that had been ground in. Yes, I know it’s a bit grotesque, but it’s literally true.

That’s why I’ve wanted to complete these episodes on the beryllium deposits of western Utah before doing any others, because telling that story includes the story of the geology of the area and how those two unusual mountains came to be there in the first place. The episodes are coming along nicely, and I have completed the geology section completely and offer it now for your enjoyment. The first episode (on the sources, uses, and geology of beryllium) will be ready in a few days; the second episode on the mining, refining, and hazards of beryllium will be ready by next week.