Thirteen Thousand Years Ago WHAT HAPPENED?

Jun 16, 2018 7:59:04 GMT -5

goatgrinder, fishnpinball, and 2 more like this

Post by 1dave on Jun 16, 2018 7:59:04 GMT -5

North American Fauna 14,000 YEARS AGO:

www.amnh.org/science/biodiversity/extinction/IntroFourteenFS.html

"Megafaunal" by whose standards?

"Megafaunal" by whose standards?

Scientists use different definitions of what counts as a large animal.

When talking about the end-Pleistocene extinctions, for example, some scientists refer to any animal over 5 kg as "large." Using this definition, about 90% of the genera dying out in North America 11,000 calendar years ago could be described as large.

Other scientists restrict the term "megafaunal" to refer to any animal over 100 lbs (~44 kg). Under this definition, only about three-quarters of the species that went extinct fit the "megafaunal" bill.

www.livescience.com/51793-extinct-ice-age-megafauna.html

1. North American horses

Remains of North America's extinct horses.

Credit: Copyright AMNH D. Finnin

European settlers introduced horses when they landed in the New World. But little did they know the thunderous sound of ancient horses' hooves once covered the continent.

Ancient horses lived in North America from about 50 million to 11,000 years ago, when they went extinct at the end of the last ice age, said Ross MacPhee, a curator of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

"One of the great peculiarities of this extinction is that they died out in North America, yet managed to survive in Eurasia and Africa, which is why we still have horses and their relatives — donkeys and asses — today," MacPhee said.

2. Glyptodon

A species of Glyptodon on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Credit: Copyright AMNH | D. Finnin

Glyptodon looked like a supersize version of its distant relative, the armadillo. Like its cousin, Glyptodon protected itself with a shell made of bony plates.

The armored, 1-ton creature likely traveled to North America from South America via the Isthmus of Panama, a land bridge that connects the two Americas, MacPhee told Live Science.

After reaching North America about 2 million years ago, Glyptodon prospered in what is now coastal Texas and Florida, he said. But the herbivorous critter has been extinct for 10,000 years, MacPhee said.

3. Mastodons

A mastodon with its long, curving tusks.

Credit: Copyright AMNH D. Finnin

Mastodons (Mammut) entered North America about 15 million years ago, traveling over the Bering Strait land bridge, long before their relative, the mammoth, according to the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre in Canada.

They were also more primitive than their mammoth cousins. For instance, mastodons had less-complex teeth — cone-shaped cusps on their molars — that helped them crunch on the leaves, twigs and branches of deciduous and conifer trees. They also ate wetland plants that weren't full of abrasive material found in terrestrial plants, MacPhee said. [Mammoth or Mastodon: What's the Difference?]

Mastodons are also a bit shorter than mammoths, but both species reached heights between 7 and 14 feet (2 to 4 meters), according to a 2013 Live Science piece. And both had shaggy coats that protected them from the cold.

However, mastodons had long, curved tusks that measured up to 16 feet (4.9 meters) long. Mammoths, in contrast, sported curlier tusks.

4. Mammoths

A mammoth.

Credit: Copyright AMNH J. Beckett and D. Finnin

Mammoths (Mammuthus) traveled to North America about 1.7 million to 1.2 million years ago, according to the San Diego Zoo. Although there are some anatomical differences between mammoths and mastodons, both are members of the proboscidean family. Mammoths had fatty humps on their backs that likely provided them with nutrients and warmth during icy periods, according to a February 2013 piece in Live Science.

Mammoths also had flat, ridged molars — a structure that helped them slice through fibrous vegetation, unlike the cusped teeth of the mastodon, MacPhee said. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed]

In addition, mammoths are more closely related to modern elephants, especially the Asian elephant, than mastodon, MacPhee said.

5. Short-faced bear

The skeleton of a short-faced bear.

Credit: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Despite its name, this enormous bear didn't actually have a short face. But in comparison to its long arms and legs, it looked like it did, MacPhee said. He compared it to a grizzly bear on stilts, as its limbs were at least one-third longer than those of a modern grizzly.

"It had very long forelimbs and hind limbs," which likely helped it run at high speeds, he said. Modern bears are capable of short bursts of speed, "but they're not runners," he said.

However, the bear's long limbs still perplex scientists.

"One idea is that short-faced bears ran down their prey like cats do, but for a whole number of reasons, that is no longer the preferred argument," he said. "We don't know why they were adapted to having long legs."

Now, researchers are looking for clues that may reveal whether the carnivore was a hunter, a scavenger or both, MacPhee said.

6. Dire wolf

A dire wolf.

Credit: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Dire-wolf bones are plentiful in California's La Brea Tar Pits and Wyoming's Natural Trap Cave. These skeletons show that dire wolves (Canis dirus) were about 25 percent heavier than modern gray wolves (Canis lupus), weighing between 130 and 150 lbs. (59 to 68 kg), according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

However, the dire wolf had shorter limbs than C. lupus, suggesting it wouldn't have won any races against its younger relative, the museum reported.

Some researchers wonder whether dire wolves are genetically different from modern wolves, or whether they're hybrids of different wolves that interbred with one another.

"Wolves and dire wolves came from a common source, and the dire wolves evolved in a slightly different direction," MacPhee said.

7. American cheetah

The American cheetah stood a little taller than the modern cheetah, with a shoulder height of about 2.75 feet (0.85 meters) and a weight of about 156 lbs. (70 kg). However, the American cheetah probably wasn't as fast: It had slightly shorter legs, which likely made it a better climber than a runner, according to the zoo.

Researchers named it Miracinonyx inexpectatus — mira means "wonderful" in Latin, and acinonyx and onyx come from the Greek words for "no movement," (based on the false perception that cheetahs don't have retractable claws) and claw, respectively, the zoo said. Inexpectatus is Latin for "unexpected," giving the big cat a name that translates roughly into "wonderful unexpected cheetah with immobile claws." [Life of a Big Cat: See Stunning Photos of Cheetahs]

Researchers dated the first known M. inexpectatus fossil, found in modern-day Texas, to the Pliocene, between 3.2 million and 2.5 million years ago, according to the zoo. They went extinct about 12,000 years ago.

8. Ground sloth

A ground sloth.

Credit: Copyright AMNH D. Finnin

When President Thomas Jefferson learned about a strange claw fossil found in Ohio, he asked explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to search for giant lions during their western trek to the Pacific. The claw, however, didn't belong to a lion. It was part of Megalonyx, an extinct ground sloth, MacPhee said. [Top 10 Intrepid Explorers]

Like Glyptodon, Megalonyx traveled to North America from South America. In fact, ground-sloth fossils indicate that these animals began living in South America about 35 million years ago, according to the zoo.

Researchers uncovered a 4.8-million-year-old Megalonyx fossil in Mexico, and later, specimens were found in present-day America, especially in areas that used to have forests, lakes and rivers. During warmer periods, called interglacials, Megalonyx made it as far north as the Yukon and Alaska, MacPhee said.

"But when it got cold, the sloth really wasn't built for that type of thing, so it headed south," he said.

Megalonyx jeffersonii stood about 9.8 feet (3 m) tall and weighed an estimated 2,205 lbs. (1,000 kg). It survived until about 11,000 years ago, the zoo reported.

9. Giant beaver

The giant beaver (Castoroides) is mostly known from its fossils in the Great Lakes region, which is "perhaps no surprise for a beaver," MacPhee said. But other fossil finds show the giant lived as far south as South Carolina and in the American Northeast.

Like Megalonyx, the giant beaver ventured into Alaska and the Yukon during the interglacial periods, but retreated south when temperatures dropped, MacPhee said.

Castoroides was enormous for a beaver — it weighed up to 125 lbs. (57 kg), much larger than the roughly 44-lb. (20-kg) North American beaver (Castor canadensis) that exists today. Interestingly, modern beaver remains are found in the same deposits as those of their ancient relatives, suggesting they had similar lifestyles, MacPhee said.

10. Camels

Yesterday's camel.

Credit: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Camels that once roamed North America are called Camelops, Latin for "yesterday's camel." However, Camelops is more closely related to llamas than to today's camels, the zoo reported.

Camelops and its ancestors were no strangers to the states. Fossils show that the camelid family arose in North America during the Eocene period, about 45 million years ago, the zoo said. It lived in open spaces and dry areas, but it's unclear whether it could conserve water as modern camels do, MacPhee said.

Camelops stood about 7 feet tall (2.2 m) at its shoulder, weighed up to 1,764 lbs. (800 kg) and had a short tail.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @laurageggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

www.amnh.org/science/biodiversity/extinction/IntroFourteenFS.html

North America - Giant Beasts!

When humans first entered North America is hotly debated. However, many scientists believe that humans arrived comparatively recently, long after the end of the last major glaciation (about 20,000 calendar years ago). The earliest radiocarbon dates documenting human presence in either North or South America that are widely accepted are only on the order of 12,000-13,000 years ago (about 14,000 calendar years ago).

The most obvious difference concerns the mammalian megafauna. Today there are only about a dozen species of North American mammals that are megafaunal (greater than 100 lbs in body size). As recently as 11,000 calendar years ago, there were more than three times that number. Whatever the exact date may turn out to be, we know from the archeological and paleontological records that, when humans first arrived in the New World, they entered a faunal landscape that greatly differed from the one that we live in today.

Their ranks included the Woolly Mammoth, a close relative of living elephants, and Giant Ground Sloths whose closest living relatives are the comparatively tiny Tree Sloths of South America. In addition to these species, there were American horses, American camels, American lions, and a host of less familiar creatures. Within a period possibly as short as 400 years, the last representatives of these species (and many others, to a total of perhaps 135 on both continents) had become extinct.

What happened to all these mammals?

When humans first entered North America is hotly debated. However, many scientists believe that humans arrived comparatively recently, long after the end of the last major glaciation (about 20,000 calendar years ago). The earliest radiocarbon dates documenting human presence in either North or South America that are widely accepted are only on the order of 12,000-13,000 years ago (about 14,000 calendar years ago).

The most obvious difference concerns the mammalian megafauna. Today there are only about a dozen species of North American mammals that are megafaunal (greater than 100 lbs in body size). As recently as 11,000 calendar years ago, there were more than three times that number. Whatever the exact date may turn out to be, we know from the archeological and paleontological records that, when humans first arrived in the New World, they entered a faunal landscape that greatly differed from the one that we live in today.

Their ranks included the Woolly Mammoth, a close relative of living elephants, and Giant Ground Sloths whose closest living relatives are the comparatively tiny Tree Sloths of South America. In addition to these species, there were American horses, American camels, American lions, and a host of less familiar creatures. Within a period possibly as short as 400 years, the last representatives of these species (and many others, to a total of perhaps 135 on both continents) had become extinct.

What happened to all these mammals?

"Megafaunal" by whose standards?

"Megafaunal" by whose standards?Scientists use different definitions of what counts as a large animal.

When talking about the end-Pleistocene extinctions, for example, some scientists refer to any animal over 5 kg as "large." Using this definition, about 90% of the genera dying out in North America 11,000 calendar years ago could be described as large.

Other scientists restrict the term "megafaunal" to refer to any animal over 100 lbs (~44 kg). Under this definition, only about three-quarters of the species that went extinct fit the "megafaunal" bill.

www.livescience.com/51793-extinct-ice-age-megafauna.html

10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America

By Laura Geggel, Senior Writer | August 15, 2015 08:28am ET

10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America

Until the end of the last ice age, American cheetahs, enormous armadillolike creatures and giant sloths called North America home. But it's long puzzled scientists why these animals and other megafauna — creatures heavier than 100 lbs. (45 kilograms) — went extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Rapid warming periods called interstadials and, to a lesser degree, ice-age people who hunted animals are responsible for the disappearance of the continent's megafauna, according to a study published in July in the journal Science. Other studies have placed more blame on humans, and some researchers say many factors are to blame.

Both research and the debate surrounding the reasons for the extinction of these animals will undeniably continue. In the meantime, researchers continue to find fossils of these massive creatures. Here's a look at 10 extinct animals from the last North American ice age, and what scientists know about their lives. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

By Laura Geggel, Senior Writer | August 15, 2015 08:28am ET

10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America

Until the end of the last ice age, American cheetahs, enormous armadillolike creatures and giant sloths called North America home. But it's long puzzled scientists why these animals and other megafauna — creatures heavier than 100 lbs. (45 kilograms) — went extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Rapid warming periods called interstadials and, to a lesser degree, ice-age people who hunted animals are responsible for the disappearance of the continent's megafauna, according to a study published in July in the journal Science. Other studies have placed more blame on humans, and some researchers say many factors are to blame.

Both research and the debate surrounding the reasons for the extinction of these animals will undeniably continue. In the meantime, researchers continue to find fossils of these massive creatures. Here's a look at 10 extinct animals from the last North American ice age, and what scientists know about their lives. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

1. North American horses

Remains of North America's extinct horses.

Credit: Copyright AMNH D. Finnin

European settlers introduced horses when they landed in the New World. But little did they know the thunderous sound of ancient horses' hooves once covered the continent.

Ancient horses lived in North America from about 50 million to 11,000 years ago, when they went extinct at the end of the last ice age, said Ross MacPhee, a curator of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

"One of the great peculiarities of this extinction is that they died out in North America, yet managed to survive in Eurasia and Africa, which is why we still have horses and their relatives — donkeys and asses — today," MacPhee said.

2. Glyptodon

A species of Glyptodon on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Credit: Copyright AMNH | D. Finnin

Glyptodon looked like a supersize version of its distant relative, the armadillo. Like its cousin, Glyptodon protected itself with a shell made of bony plates.

The armored, 1-ton creature likely traveled to North America from South America via the Isthmus of Panama, a land bridge that connects the two Americas, MacPhee told Live Science.

After reaching North America about 2 million years ago, Glyptodon prospered in what is now coastal Texas and Florida, he said. But the herbivorous critter has been extinct for 10,000 years, MacPhee said.

3. Mastodons

A mastodon with its long, curving tusks.

Credit: Copyright AMNH D. Finnin

Mastodons (Mammut) entered North America about 15 million years ago, traveling over the Bering Strait land bridge, long before their relative, the mammoth, according to the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre in Canada.

They were also more primitive than their mammoth cousins. For instance, mastodons had less-complex teeth — cone-shaped cusps on their molars — that helped them crunch on the leaves, twigs and branches of deciduous and conifer trees. They also ate wetland plants that weren't full of abrasive material found in terrestrial plants, MacPhee said. [Mammoth or Mastodon: What's the Difference?]

Mastodons are also a bit shorter than mammoths, but both species reached heights between 7 and 14 feet (2 to 4 meters), according to a 2013 Live Science piece. And both had shaggy coats that protected them from the cold.

However, mastodons had long, curved tusks that measured up to 16 feet (4.9 meters) long. Mammoths, in contrast, sported curlier tusks.

4. Mammoths

A mammoth.

Credit: Copyright AMNH J. Beckett and D. Finnin

Mammoths (Mammuthus) traveled to North America about 1.7 million to 1.2 million years ago, according to the San Diego Zoo. Although there are some anatomical differences between mammoths and mastodons, both are members of the proboscidean family. Mammoths had fatty humps on their backs that likely provided them with nutrients and warmth during icy periods, according to a February 2013 piece in Live Science.

Mammoths also had flat, ridged molars — a structure that helped them slice through fibrous vegetation, unlike the cusped teeth of the mastodon, MacPhee said. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed]

In addition, mammoths are more closely related to modern elephants, especially the Asian elephant, than mastodon, MacPhee said.

5. Short-faced bear

The skeleton of a short-faced bear.

Credit: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Despite its name, this enormous bear didn't actually have a short face. But in comparison to its long arms and legs, it looked like it did, MacPhee said. He compared it to a grizzly bear on stilts, as its limbs were at least one-third longer than those of a modern grizzly.

"It had very long forelimbs and hind limbs," which likely helped it run at high speeds, he said. Modern bears are capable of short bursts of speed, "but they're not runners," he said.

However, the bear's long limbs still perplex scientists.

"One idea is that short-faced bears ran down their prey like cats do, but for a whole number of reasons, that is no longer the preferred argument," he said. "We don't know why they were adapted to having long legs."

Now, researchers are looking for clues that may reveal whether the carnivore was a hunter, a scavenger or both, MacPhee said.

6. Dire wolf

A dire wolf.

Credit: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Dire-wolf bones are plentiful in California's La Brea Tar Pits and Wyoming's Natural Trap Cave. These skeletons show that dire wolves (Canis dirus) were about 25 percent heavier than modern gray wolves (Canis lupus), weighing between 130 and 150 lbs. (59 to 68 kg), according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

However, the dire wolf had shorter limbs than C. lupus, suggesting it wouldn't have won any races against its younger relative, the museum reported.

Some researchers wonder whether dire wolves are genetically different from modern wolves, or whether they're hybrids of different wolves that interbred with one another.

"Wolves and dire wolves came from a common source, and the dire wolves evolved in a slightly different direction," MacPhee said.

7. American cheetah

The American cheetah stood a little taller than the modern cheetah, with a shoulder height of about 2.75 feet (0.85 meters) and a weight of about 156 lbs. (70 kg). However, the American cheetah probably wasn't as fast: It had slightly shorter legs, which likely made it a better climber than a runner, according to the zoo.

Researchers named it Miracinonyx inexpectatus — mira means "wonderful" in Latin, and acinonyx and onyx come from the Greek words for "no movement," (based on the false perception that cheetahs don't have retractable claws) and claw, respectively, the zoo said. Inexpectatus is Latin for "unexpected," giving the big cat a name that translates roughly into "wonderful unexpected cheetah with immobile claws." [Life of a Big Cat: See Stunning Photos of Cheetahs]

Researchers dated the first known M. inexpectatus fossil, found in modern-day Texas, to the Pliocene, between 3.2 million and 2.5 million years ago, according to the zoo. They went extinct about 12,000 years ago.

8. Ground sloth

A ground sloth.

Credit: Copyright AMNH D. Finnin

When President Thomas Jefferson learned about a strange claw fossil found in Ohio, he asked explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to search for giant lions during their western trek to the Pacific. The claw, however, didn't belong to a lion. It was part of Megalonyx, an extinct ground sloth, MacPhee said. [Top 10 Intrepid Explorers]

Like Glyptodon, Megalonyx traveled to North America from South America. In fact, ground-sloth fossils indicate that these animals began living in South America about 35 million years ago, according to the zoo.

Researchers uncovered a 4.8-million-year-old Megalonyx fossil in Mexico, and later, specimens were found in present-day America, especially in areas that used to have forests, lakes and rivers. During warmer periods, called interglacials, Megalonyx made it as far north as the Yukon and Alaska, MacPhee said.

"But when it got cold, the sloth really wasn't built for that type of thing, so it headed south," he said.

Megalonyx jeffersonii stood about 9.8 feet (3 m) tall and weighed an estimated 2,205 lbs. (1,000 kg). It survived until about 11,000 years ago, the zoo reported.

9. Giant beaver

The giant beaver (Castoroides) is mostly known from its fossils in the Great Lakes region, which is "perhaps no surprise for a beaver," MacPhee said. But other fossil finds show the giant lived as far south as South Carolina and in the American Northeast.

Like Megalonyx, the giant beaver ventured into Alaska and the Yukon during the interglacial periods, but retreated south when temperatures dropped, MacPhee said.

Castoroides was enormous for a beaver — it weighed up to 125 lbs. (57 kg), much larger than the roughly 44-lb. (20-kg) North American beaver (Castor canadensis) that exists today. Interestingly, modern beaver remains are found in the same deposits as those of their ancient relatives, suggesting they had similar lifestyles, MacPhee said.

10. Camels

Yesterday's camel.

Credit: Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Camels that once roamed North America are called Camelops, Latin for "yesterday's camel." However, Camelops is more closely related to llamas than to today's camels, the zoo reported.

Camelops and its ancestors were no strangers to the states. Fossils show that the camelid family arose in North America during the Eocene period, about 45 million years ago, the zoo said. It lived in open spaces and dry areas, but it's unclear whether it could conserve water as modern camels do, MacPhee said.

Camelops stood about 7 feet tall (2.2 m) at its shoulder, weighed up to 1,764 lbs. (800 kg) and had a short tail.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @laurageggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

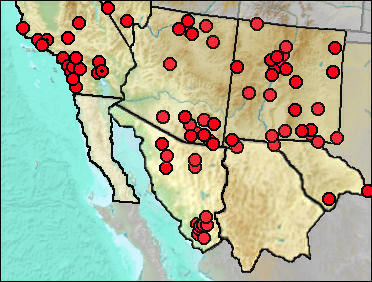

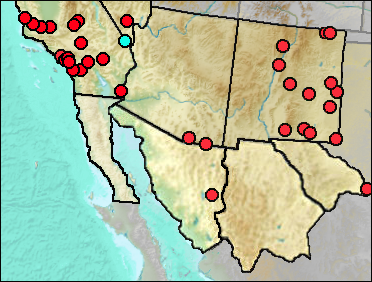

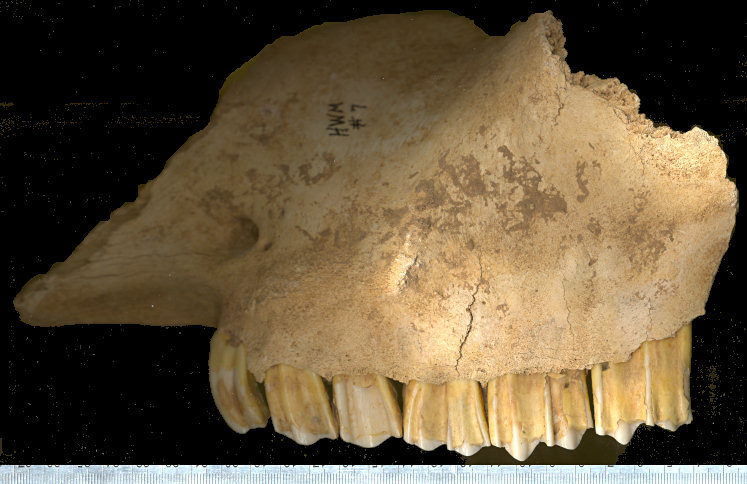

Bison/Bos—Bison or CattlePleistocene distribution of Bison/Bos

Bison/Bos—Bison or CattlePleistocene distribution of Bison/Bos Bison sp.—BisonPleistocene distribution of Bison sp.

Bison sp.—BisonPleistocene distribution of Bison sp. †Bison antiquus Leidy 1852—Ancient BisonPleistocene distribution of Bison antiquus

†Bison antiquus Leidy 1852—Ancient BisonPleistocene distribution of Bison antiquus

... to the New Guys from The ChatBox V.2 Crew

... to the New Guys from The ChatBox V.2 Crew